Ace landscape and portrait photographer Mobeen Ansari is a creative force to reckon with. In a candid conversation with Asma Rashid Khan, Founder and Director of Satrang Gallery in Islamabad, he shares his love for exploring Pakistan through pictures of people, places and glaciers that inspire.

Before we discuss your work, let’s start from the start; tell us about your childhood and the early experiences that made you think of art.

Well, I lost my hearing at a very young age. While growing up, I would spend most of my time lip-reading and studying people’s body language. This helped me cultivate my visual sense and I became fond of the idea of trying to understand people through art.

However, my interest in photography developed particularly after seeing this one specific photograph of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan where his son is sitting next to him and on his lap is seated his grandson, Sir Ross Masood, who happens to be my grandmother’s grandfather. This historic photo sparked an interest in me and made me want to capture memorable moments too.

My grandmother was a very dynamic lady and far ahead of her times. It seems I’ve inherited the bug from her. In addition to being a talented painter, she was also into photography. There’s a lovely photograph of hers the family has preserved where she is seen taking a picture of herself and her three sisters in the mirror. I call it the subcontinent’s first ever selfie!

You graduated as a painter from the prestigious National College of Arts, Lahore and later shifted gears to become a photographer. What led to the transition?

When I was in college, I would look at a painting and would try to capture it through the camera. Photographs always fascinated me. Although I love painting too, photography is a medium that makes me understand people better, and has over time instilled a sense of deep confidence. I have the privilege of going off to uncharted territories where language can be a barrier, but the camera blurs that line and enables me to interact with new people.

You showcase the best from all across Pakistan through its people and its natural beauty. Your book “Dharkan: Heartbeat of a Nation” features not only icons but also the common folk from different areas of the country. There’s much diversity that you’ve captured though the lens and now “Dharkan Part II” will be out soon. What inspired you to do this project?

When I was in my final year of college, like almost every other student or person, I too was questioning myself on what I was going to do or how I was going to serve this country and contribute as an artist and photographer. One fine day, while walking through the college corridors, I heard a story about a 104-year-old wrestler, how well he trained throughout his youth and what a celebrated wrestler he was. This made me realize that people are interested in other people, they talk with pride about the great things other people do, hence, I decided to make this book about the people of Pakistan.

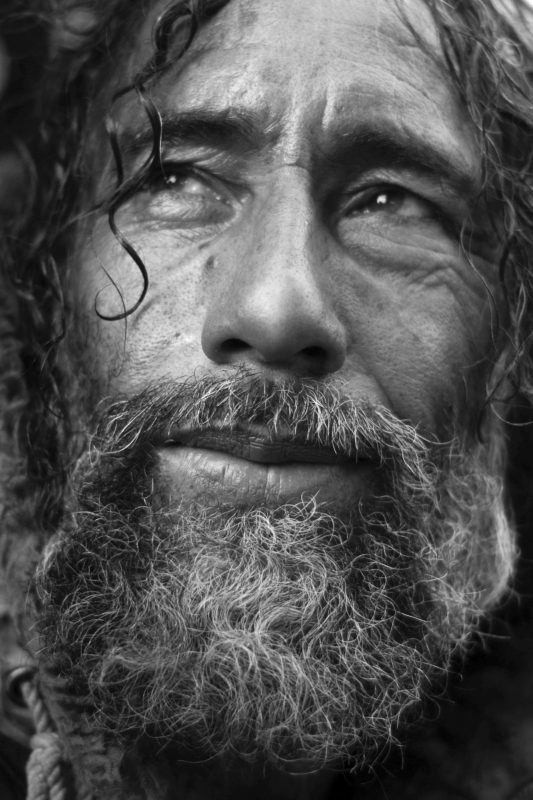

In this regard, I consider myself very lucky to have photographed people from all walks of life and I make sure that everyone gets equal space in the book; whether it’s a famous person or not; whether it’s someone from up north or down south – they are all presented in equal measure.

As a photographer, I am always striving to understand and appreciate the human spirit more and more. It’s what I do! However, to be honest, there are many times when I am faced with a language barrier; that is when it gets difficult to make the subject comfortable. Since I do not speak the same language as most of the people in rural centres across different parts of the country, what I do is, I take someone with me who can speak the same language as them.

The other thing is, I also tend to revisit certain areas and once people trust me then that makes it easier to get the job done. For example, I photographed a lady named Khushal Begum in Wakhan, the corridor that connects Pakistan with Afghanistan, a while ago when I was there. This year when I got a chance to go back, I made sure to take a print of her portrait with me to give to her. She was very happy to see it and invited me over to her place to share a meal with her family.

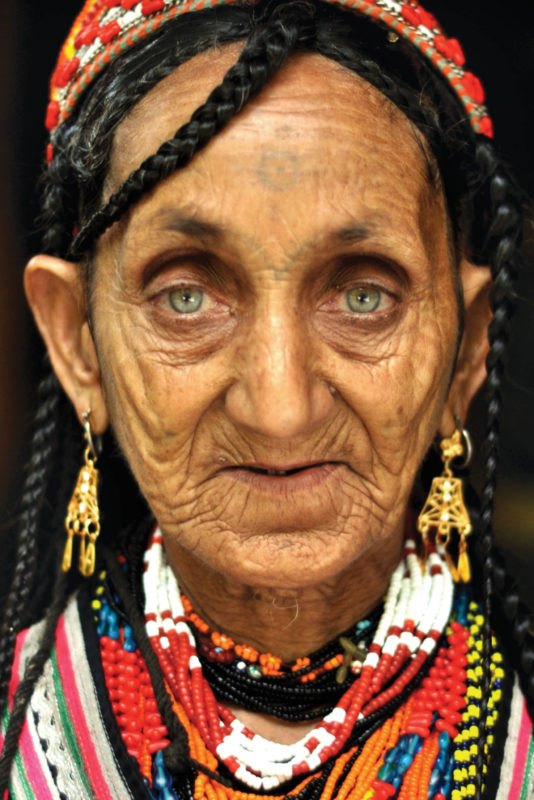

Then there was Bibi Kai in Kalash valley who had previously been photographed by National Geographic photographers. Since she had been photographed before, it was easier to work with her. In fact, her face can be found on Google as well!

In addition to people, we know that you also photograph places, heritage properties, fascinating doors, architectural beauties from a bygone era. How does that interest you?

I find them fascinating because old places, buildings and doors have so many stories to tell. They give us an idea of different places around Pakistan. By the way they are maintained or not, by their design, by the purpose for which they were made, each of these elements has a way of speaking to you about things in the past and how they used to be, how many residents have passed through, whether it was a happy space or not and so on. I love indulging in history.

You seem to be archiving the geographical, social and cultural spheres of Pakistan in a truly wonderful fashion by preserving this time in space through your photographs. How do you look at your work?

I consider my work as a study of all three genres mentioned above. Travelling through Pakistan has taught me so much. I have observed a different door in every province, and let me tell you, each one has a fascinating story of its own.

I get inspired by different things. There is this glacier in the Wakhan Corridor which really held me enthralled by its sheer scale and magnitude. It is a 1000 feet high.

Through my work, I try to reflect on various aspects of our lives. I get to know new people when I am travelling; by trying to speak with them or merely sharing the journey in silence, we are sharing an experience and creating a memory together.

Your latest project is also a labour of love – your first documentary, “Hellhole”. Selected by the New Orleans Film Festival for screening, it will also be travelling to other film festivals across the globe. Tell us more.

“Hellhole” was one small part of me trying to celebrate humanity. The primary intention here is to recognize the best among us. Through this project, which is very close to my heart, I am trying to lend dignity to a people whom many look down upon socially – the sewerage cleaners.

These unsung heroes do what no other person would do. They jump down gutter holes full of filth, with all sorts of waste swimming around them – without any protective gear. So I decided to bring them to light and make a short film. I had no script, no storyboard; armed only with a sense of responsibility, I jumped headlong into it. I hope this project can garner enough attention to their plight so that corrective measures can be taken at some policy level.