Leading journalist and media producer Fifi Haroon trudges through airport corridors and life in general with baggage that not only defines her individual history, but also provides a rare personal insight into the life of one of the most prominent families of Pakistan.

Where I live was once the sea.

Apparently waves lapped the shores where my house was later built sometime in the 1930s. That’s why it was aptly named Seafield. But enterprising as humans can sometimes be, we managed to wrestle the waters and claim a home.

And so my story began… on a land we won back from the sea and my newly adopted countrymen, the British. Coming “home” to Pakistan is always a journey of mixed emotions and mind wars; a flight that separates fantasy from home truths and defensive rants from fresh misgivings. I drag along my suitcase of memories with me through long airport corridors. It has uneven wheels and bulges at the seams. If it was real rather than imagined, the airline would tag on little alerts on it.

Karachi is now my second home. Once a cold, distant destination across the seas, London is now my first. The distance between one and two is traversed by a flight that stutters through Dubai or Doha. I am not one of those that likes to jet back to Karachi on a heaving PIA plane. It’s all too soon and sudden. An abbreviated version of the worst of Pakistan with squealing children, overflowing toilets and aging flight attendants.

I’d rather wait till the oven heat of Karachi hits me square between the eyes as I make my way across the immigration barriers to reluctantly join the NICOP queue. I loathe that little laminated piece of “foreign-ness” I have to use as an invite to return. After all, wherever our fortunes take us, it’s still Dil Dil Pakistan. But am I a woman of the heart or the mind?

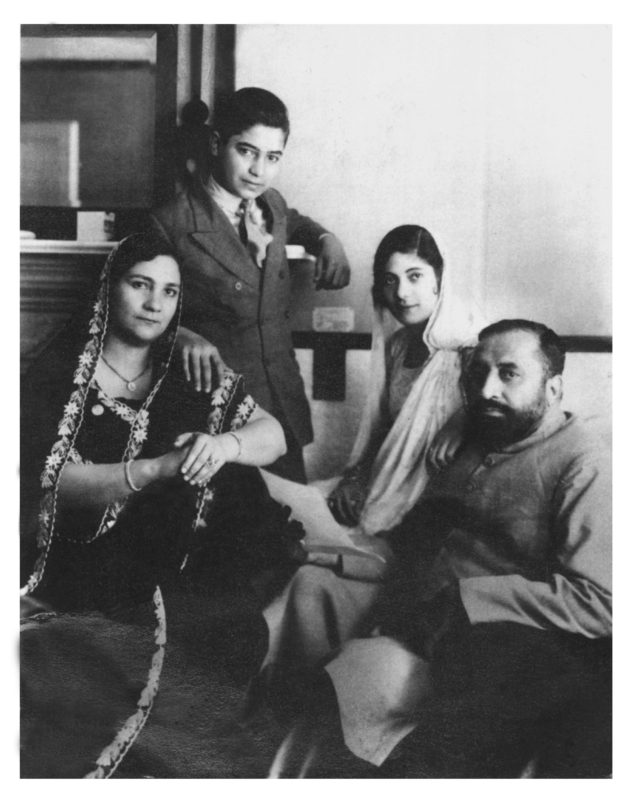

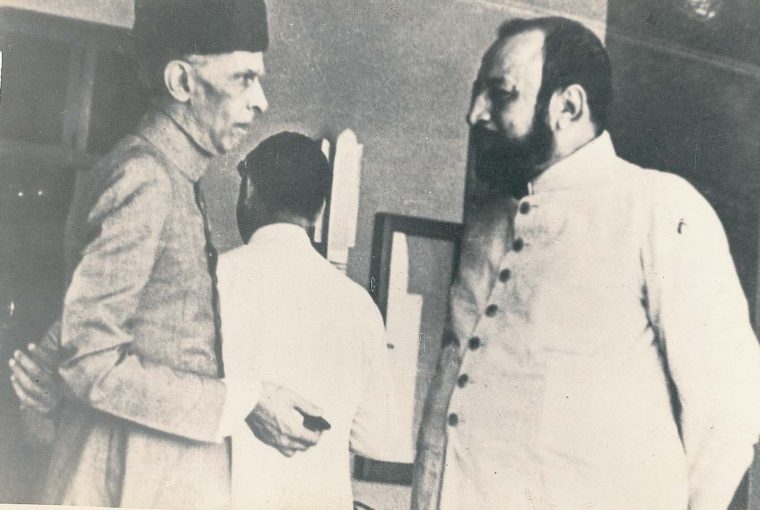

There is so much to remember about Pakistan. Some of it experienced second-hand through my parents but it lives in my mind as personal history. In the 1940s my home apparently became a hub of passionate resistance to foreign rule. My grandfather, Sir Abdullah Haroon, and Mr Jinnah had been to school together at the Sindh Madrassa and their friendship matured into political strategizing for a new country to be named Pakistan. I had of course not opened my eyes to the world then. But my childhood was filled with stories of the freedom struggle as it played out in the lives of my family. The first emblem of this burgeoning nation was hoisted atop the flag pole on our roof. It seems the tailor stitched the moon and stars together for its first sky and brought the prototype for the Quaid’s approval. Alas for the poor man, Mr Jinnah was not satisfied. He wanted the white of the flag – the part that encompassed the dreams of the future country’s minorities – to be extended, to be fair to all Pakistanis of any ilk of belief. Only then was my uncle, Yusuf Haroon instructed to raise the first Pakistani flag on Seafield. It is a lesson many have forgotten, but to me this is the Pakistan I believe in.

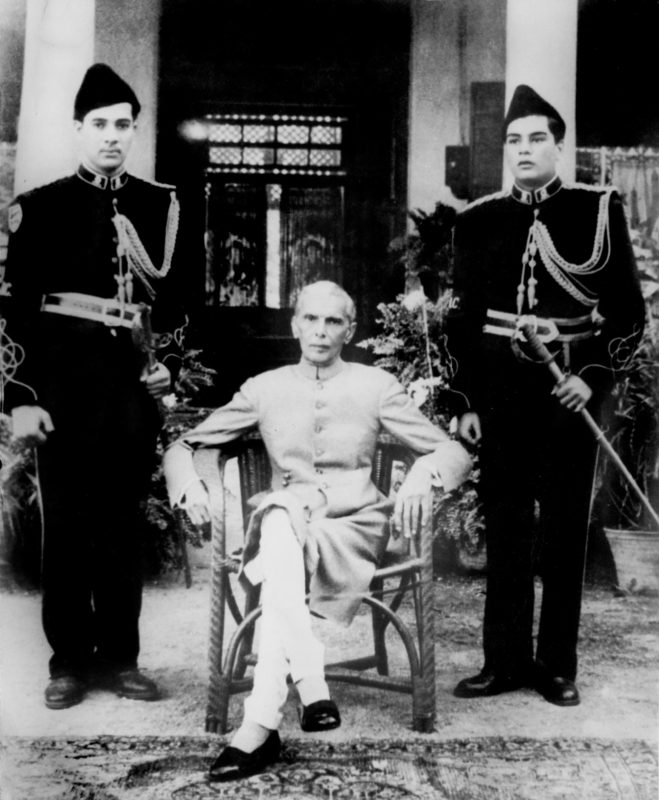

When Mr Jinnah became the first Governor-General of a free Pakistan in 1947 my father Saeed Haroon, who was one of the young Turks of the freedom movement, became his aide-de-camp. In my home in Chelsea in London a photograph of my handsome uniformed father standing stoutly by Mr Jinnah is among the memorable frames that dot the side table. Remembrance of things past; the fabric of my life intertwined with many lives and entangled in the history of a new nation – Pakistan.

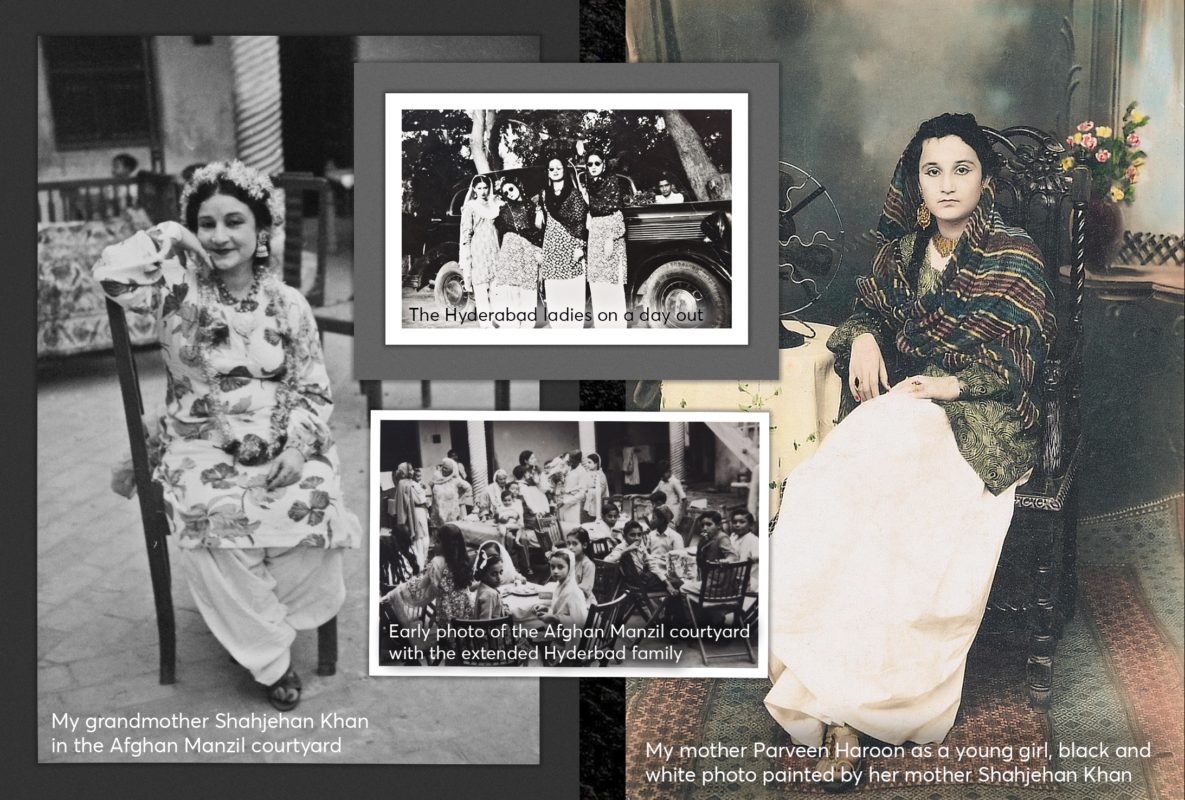

But isn’t our life always split between places with heart strings tugging in every direction? Mine certainly has been. As a child my two grandmothers, Lady Nusrat Haroon and Shahjehan Khan, embodied pillars of strength in Karachi and Hyderabad – and my life changed gear depending on which grandmother’s roof covered my head. In the main it was Lady Haroon – my Persian grandmother whose word was law in Seafield. A woman that could make Margaret Thatcher look like she was made out of cotton wool not iron. It was whispered she once gave one of my uncles a sound thrashing with her slipper witnessed by his staff when he was a high official in the Ayub Khan government because he didn’t respond quickly enough to her call.

Both matriarchs ruled their caboodles like empresses but Amma as we all called my maternal grandmother was perhaps less intimidating to me because her throne was a relatively modest khaat (camp bed) in the main room of the Hyderabad house and the multiple doors to that room were always open. As kids we would eagerly climb on top of her bed and survey the world from her vantage point. Amma would continue to smoke half-cigarettes nonchalantly and yield to our pleas to tell us yet again about Adi Sonal, a Sindhi folk heroine of much wonder. Amma wasn’t surrounded by the stellar political cast of the Haroon home, nor were the historical questions that plagued Pakistan played out at her dinner table. Mind you, she was still queen of her own castle.

I come from a family of strong, bossy women on both sides. Women who always got their way. Women who led their men and their children through familial battlefields. It is an inheritance I treasure. The Haroon girls before me went to jail in the freedom movement, joined the country’s first women’s National Guard, learnt how to do a lathi (baton) charge and also managed to attend tea parties at Buckingham palace. They were proverbial wonder women who married well and bore many children. The career woman amongst them was Shaukat Haroon – or Doctor-Aunty as she was called – whose day job consisted of helping Karachi’s women grow their clan at Lady Dufferin Hospital.

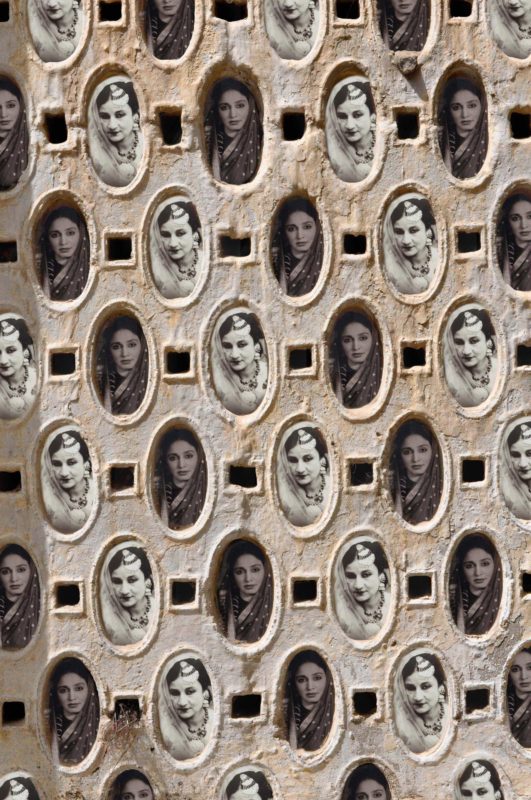

Doctor-Aunty moonlighted as a central member of Pakistan’s equivalent of the Bloomsbury set. A circle of friends who included the erstwhile educationist “Baji” Majeed Malik (who went on to form the PECHS Women’s College), the artist Sadequain and the poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz. She soon became the latter’s muse and he devoted many lines to profess his ardour including some say the iconic “Gulon mein rung bharrey,” immortalised by Mehdi Hasan. A treasured recording of Faiz reading to Dr. Shaukat Haroon under the shade of a banyan tree at her Karachi residence remains in the family. When she died suddenly from a heart attack, Faiz reportedly locked himself in his room at the Flashman’s Hotel in Lahore for two days. He emerged with an elegy in hand which was was sung soulfully many years later by Farida Khanum:

“Chand nikle kisi jaanib teri zebayi ka

Rang badle kissi surat shab-e-tanhai ka.”

I recall finding first signed editions of Faiz’s poems around the house and later, much later, wondered if a man would ever mourn my passing with such literary finesse. Pitiably, the men of today do not have the poetic passion of a Faiz or Faraz and I am probably destined to die unsung.

In the winter months we abandoned the more sophisticated environs of Seafield for the small-town pleasures of Sindh’s second city. This dichotomy embraced the two extremes of my growing years in Pakistan – the political and the personal. In the early years, until I turned ten or so, we used to take the train. I think it was called the Tezgam though it took around three hours to transport us to our temporary home away from home. In later years my father bought a Dodge Dart that he fondly named Rosanna. Rosanna’s speedometer was pushed to the limit to achieve the same feat in an hour while we kids squealed in delight at the back. Surely we had the bravest father in the world? No one could outrun him at the wheel of his old faithful.

Seafiield – the Haroon home on Sir Abdullah Haroon Road.

Seafiield – the Haroon home on Sir Abdullah Haroon Road.

The Tezgam of the 1970s had uniformed bearers who would bring us grubby breakfast menus – though I am not sure if this is something which actually was or I concocted with the passing of time. What I do remember is that I looked forward to the morning meal for days. Two fried eggs, sunny side up, toast and butter. Nothing particularly different from what we could have had at home but these eggs tasted of adventure and discovery. As the train moved slowly out of the confines of the Cantonment railway station and chugged along the open fields of Sindh I looked out to my Pakistan unfolding before me. There I was, racing towards freedom in the Tezgam. Further and further away from the urban finesse and political circus of Karachi. I could walk, I could run, I would not be scolded. There were no dignitaries to stumble over.

My mother’s old home, 55 Afghan Manzil, was a cluster of little abodes around a central courtyard that was always full of hustle and bustle. Innumerable grand aunts and uncles entered and left from a multitude of doors. Everyone was much heartier than in Karachi. Whereas Karachi was a seductive, grander passion, Hyderabad was all tenderness in my mind. It was honeyed romance. The topographical equivalent of my mother, Parveen. My maternal family was of Pakhtun stock softened by Sindh’s sweetness and encapsulated in a fragrant embrace. In Karachi we walked tall and held our head high in high society. In Hyderabad we were held. Kisses were planted on our cheeks by endless relatives. I could choose my lunch from half a dozen kitchens; everyone was eager to pamper and feed the city cousins.

Equally I could wander into the lanes that radiated from the house and visit the more humble homes of common folk and play with Akhtari, who was a similar age to me. I would sit on a small wooden stool near the makeshift clay stove while Akhtari’s mother would knead some dough freshly and make us ghee laden bread to share. On the way back I would stop by the small neighbourhood store to pick up toffees with the one rupee a day Amma used to give me as pocket money. It was bliss to be alive and to be young was very heaven.

At night we would sleep in the courtyard under heavy razayis (duvets) and mosquito nets. Peering through the filigree of the net at the open starlit sky, a chorus of families huddled together and told stories of the past until we fell asleep in happy repose.

There was also dashing young Aftab, a distant cousin in his late teenage years who had a motorbike, a curled moustache and RayBan glasses. As an eight or nine year old I would sit on the back seat and be driven around the dusty streets of the neighbourhood. This was as close as I got to seeing the real Pakistan as a child – in fast motion on the pillion seat.

Most of our time in Hyderabad was occupied by watching movies again and again and again. My grandfather, Allahnawaz Khan owned a cinema called New Majestic which was run mainly by my uncle, Jahangir. If seats were free we could fit ourselves in every day and stare wide-eyed at Waheed Murad serenading Zeba while sharing newspaper-wrapped pakoray (fritters) from the cinema kiosk. Today back in Karachi and several decades older, it’s popcorn and nacho chips in the new, posh cineplexes. A little less shiny and more woebegone since Deepika’s slender charms and Ranveer’s six-pack were banished for a few months. These days the cinema owners are trying to shrug off their self-imposed exile but who knows how it will go.

Alongside progress, much of my childhood has been erased from the city. For me the most devastating change has been the side-lining of Jahangir Kothari Parade, once the architectural high point of Karachi now robbed of its pre-eminence by criss-crossing flyovers and rude commercial ambitions. As kids we used to savour our afternoon trips to the Parade, mostly spent trying to climb the pavilion before inevitably slipping down. Today most people slip by the promenade.

So here I am visiting the ghosts of my life. Like the bifurcation of my childhood, I am split in two yet again between London and Karachi. Afghan Manzil was sold off, my mother’s family disintegrated into thin air and different corners of the world. Yet the Hyderabad of my past is packed tenderly into my suitcase of memories. And among the folds is purana (old) Karachi and Seafield. I try desperately to keep these two halves whole in my imagination.

The past is my journey to myself. My father’s family taught me the ways of the world, my mother’s family taught me the ways of the heart. Without either I would be incomplete.

Comments are closed.