Karachi and New York City may not be as worlds apart as one might think at first glance. Filmmaker Hasan Zaidi shares a personal perspective…

Ask any random person to name a city around the world similar to New York City and they will most likely struggle. London perhaps? Both are thriving financial centres, offer a lot in terms of cultural enrichment opportunities and are tremendously cosmopolitan. Both are part of the Western world and English is the lingua franca. But some things will not fully gel.

New York is too unique, they’d admit; almost the entire world is represented in the city (and not just because it is home to the United Nations); it is far more modern; it has a vibe unlike any other city; it is more welcoming of outsiders etcetera etcetera etcetera…

So, yes, finding a city to liken to the Big Apple would be difficult for anyone. What I can pretty much guarantee, however, is that the city they will not reference is Karachi.

And yet…

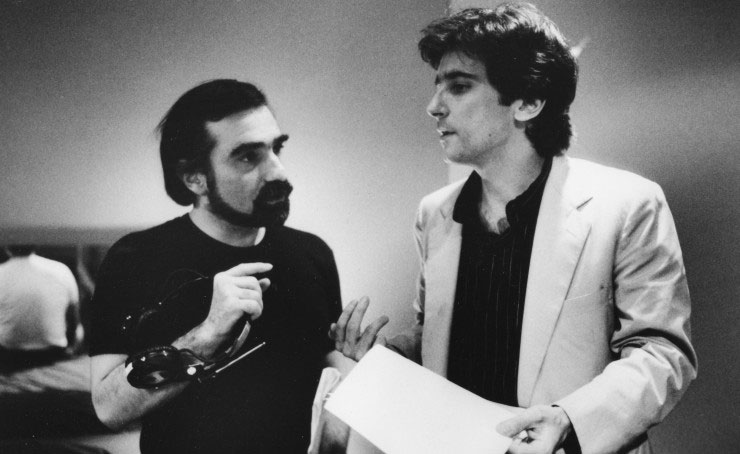

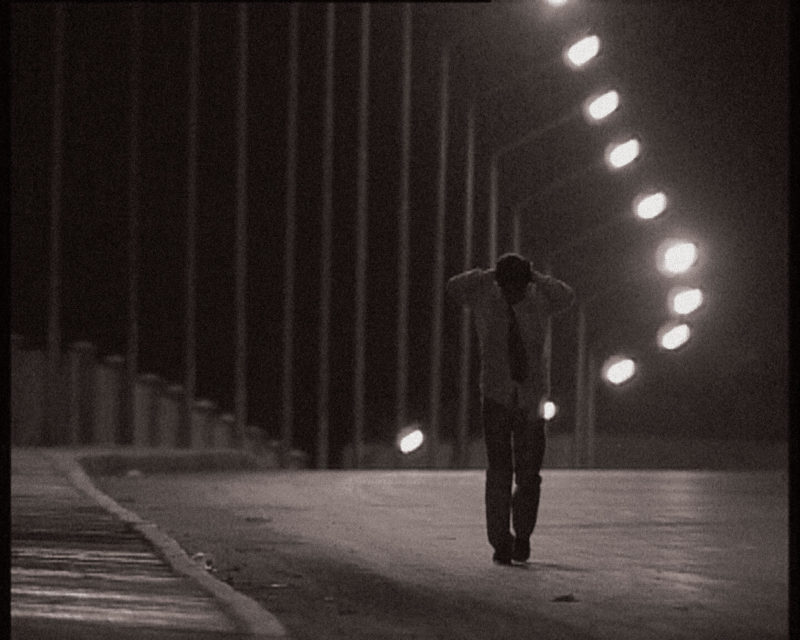

In 1991, I saw After Hours, one of director Martin Scorsese’s most underrated films. The film actually came out in 1985 and did not do particularly well at the box office. It was considered a deviation from the heights he’d reached with films such as 1973’s Mean Streets, 1976’s Taxi Driver and 1980’s Raging Bull. The film noir takes place in one night in New York, during which a young professional data operator has a series of surreal misadventures on the streets when he ventures out for a date in Soho and is left without any money. The film is often unfairly tagged with the yuppie-in-peril genre that includes films such as 1990’s terrible Tom Hanks vehicle Bonfire of the Vanities; Scorsese’s film owes its influences far more to Kafka.

The film was of course very much about New York City of the 1980s. But all I could think of as I watched it was how much it reminded me of Karachi.

I was fascinated with the idea of a protagonist suddenly finding a familiar city become unfamiliar and how that perception feeds into a sense of threat. It recalled to me Karachi’s unbridled growth and subsequent geographical polarization, summarized usually by the (only vaguely accurate) characterization ‘Bridge ke iss paar rehte ho ya uss paar?’ (Do you live on ‘this’ side of the Clifton

Bridge or the ‘other’ side?).

The assumption in that characterization – that people living on either side of the bridge are different from each other, in terms of class, language and values and ‘never the twain shall meet’ – is mirrored to this day by some people in New York City. Manhattan residents, for instance, rarely venture out to Queens. Some of them look down upon even the increasingly gentrified and hip Brooklyn.

I was fascinated too by how people can exist in a city and be unaware of it beyond their own little bubble. As a journalist back in Karachi in the 1990s, I was increasingly aware of this disconnect: most of the elite had never ventured into even the oldest and most central parts of the city such as Lyari.

Unlike New York, Karachi is not divided into distinct boroughs such as Manhattan or Brooklyn or Queens. Yet it is increasingly many different cities in one. People living in Orangi in the northwest, for instance, can sometimes go years withoutinteracting (or needing to interact) with the denizens of Clifton and Defence in the south. And vice versa.

And of course, the idea of a city that never sleeps is intrinsic to both New York and Karachi. Karachi was given the title of the ‘City of Lights’ in the 1960s, which it has striven to maintain despite the worst spells of power breakdowns (or ‘loadshedding’ in common parlance). In contrast to small-town America or most other cities in Pakistan, a subterranean life exists in these two cities even in the dead of night.

I became obsessed with trying to adapt the central idea of After Hours into a film about Karachi. As a filmmaker I was also taken with the idea of exposing the lived reality of the city on film – cities had more or less disappeared from the national cinematic oeuvre in the 1980s and 1990s.

Eventually, with the help of my friend (and later celebrated novelist) Mohammad Hanif – who wrote the screenplay – I managed to make that film in 2000. Titled Raat Chali Hai Jhoom Ke, after a song made famous in a 1967 Waheed Murad film, the film told the story of a well-off software entrepreneur who lives in Clifton and has been carrying on a phone affair with a woman whose old-world charm and coyness attract him in spite of himself (keep in mind this was before the advent of mobile phones and even caller line identification). When she finally invites him to her house, he discovers she lives in Malir, an area he has little to no knowledge about. But overcome by desire he sets out to see her, only to discover upon meeting her that she 1) is married 2) has just poisoned her husband and 3) wants his help in disposing off the body.

His attempt to escape from this psychotic situation sets in motion a whole series of events over the course of the night in which he discovers a side of his city that he has never experienced before. The film was essentially a celebration of the underbelly of the city and what was remarkable was how easily the very different city of New York could be adapted to Karachi.

Karachi is not New York. Despite having a population more than double of NYC, it is nowhere as developed as a city. Most of it looks like a slum. As a tourist, looking only at the surface, it would seem laughable to even compare the two. One is vertical, the other still largely horizontal. But cities are strange creatures. You have to look within their souls to appreciate them fully.

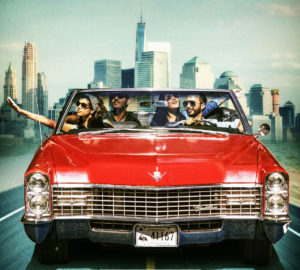

As far as Pakistan is concerned, Karachi is its New York. It is the centre of business and the media. It is the city people flock to from all parts of the country because it welcomes all. It is a city of migrants. It may not have the representation of different worldwide cultures that New York City can boast of, but it’s pretty remarkable for a South Asian city. Aside from strong representation of all the cultures of Pakistan, it is also home to significant numbers of migrants from Afghanistan, Iran, Sri Lanka, China, Burma, India and Bangladesh. More than 30 languages are spoken in Karachi. It is far more liberal on social and gender rights than the rest of Pakistan. It can be rude and it has a coded slang only those who here can appreciate. It has better beaches. If

New Yorkers can fight over where to get the best pastrami sandwiches, Karachiites can fight similarly over the best . (And if you can find aloo chaat in New York, you can find ‘New York style pizza’ in Karachi.) And yes, it has its own unique Gotham vibe.

Incidentally, the first time I visited New York City, in 1988, it was in the era before the city was ‘cleaned up’. I had grown up hearing numerous stories about violent crime in the city. As we were driving into the city at night, my friend asked me to lock the car doors – just in case someone tried to mug us at a traffic light. Visiting the elite Columbia University I noticed that the dorms had armed guards for security, which shocked me, coming as I was from the more sedate upcountry areas. On the walls at one reception were posters offering a reward for identifying the killers of a police officer who had been shot dead earlier. On a later visit in 1991, when I once took the subway alone at night, my friends were incredulous that I had actually survived without incident.

I recall these stories only to offer some perspective to those who might bring up the issue of Karachi’s violence. In 1991 it was safer to be in Karachi.

It’s also a reminder that cities can change. But it is their souls that define them.

And New York City and Karachi, to me, are soul sisters.