The painted poetry of Imran Qureshi and Aisha Khalid.

London-based art historian and museum curator Sona Datta weaves a compelling tale of retrospection based on the works of art couple, Aisha Khalid and Imran Qureshi. A poetic narrative, her piece draws upon their artistic expression and creative drive, and chronicles how their life and art are inextricably intertwined. It lists the spirit behind their emotional motivation, which is at the core of their very being, in the shape of the beating heart of their beloved country, Pakistan.

In 2011, when I visited Lahore as a curator at the British Museum, I had the good fortune of being hosted by Imran Qureshi and Aisha Khalid. It was a rich and revelatory trip but as I write this now and think back fondly to my first visit to Pakistan, and as I think about artists and their creative drive, one moment has really stayed with me.

We were returning by nightfall from a day-trip to the Rohtas Fort, a little outside of the city of Lahore, and stopped at a roadside dhaba (the traditional Punjabi equivalent of a service station). It was November and the night air was cold. As we sat wrapped in shawls, huddled on chairs around steaming cups of tea, a Pakistani painted truck illuminated with iridescent lights turned into the parking lot, the outlines of the juggernaut incandescent with neon blue and green as if some strange creature from the deep ocean had floated into our vision. But it was Qureshi’s reaction that has stayed with me. “Wow” came a quiet, slow and impassioned expression of wonder. Like a magnet Qureshi was pulled towards the spectacle as the slow moving beast came to a standstill some twenty feet away from us. With eyes transfixed, he pulled out his camera and attempted to commit the vision to memory. The playful, innocent wonder of a small child was a gift to behold.

Imran Qureshi and Aisha Khalid are leading contemporary artists from Lahore. They are also married and have recently built a new home where they work and live with their two young sons. Life and art are inextricably intertwined and at the core of their very being is the beating heart of their beloved Pakistan: a new country with an old (and important) history.

Both studied Mughal miniature painting at the National College of Arts in Lahore in the early 1990s at a time when the expansion of what a modern miniature might be was yet to be determined. Both have had a profound impact on this process of self-determination. Indeed, both students under the tutelage of visionary educators like Zahoor ul Akhlaq and Salima Hashmi found themselves at a moment when tradition and innovation were to collide in new and unexpected ways. This was a time when the burden of growing up under General Zia’s military dictatorship weighed heavily on creative and impressionable minds. At every turn there were conduits and dead ends as the NCA administration found itself playing cat and mouse with the military junta in a bid to fulfil its pedagogic duty.

During his time at NCA, Qureshi ran the student puppet society and found himself deeply embedded in all manner of dramatic arts. Performance has been a source of inspiration for many of Qureshi’s experimental ideas. While the hanging of pictures within frames on walls was never really part of the South Asian tradition, the performative has always been deeply embedded in the Indo-Pak psyche. These early activities were Qureshi’s introduction into expressing contemporary issues within traditional formats. The arts of South Asia have also always been about a rollicking good yarn and Qureshi’s pull towards story-telling started as early as the bedtime stories he listened to from his beloved grandfather, which made an indelible impression on the boy Imran’s mind.

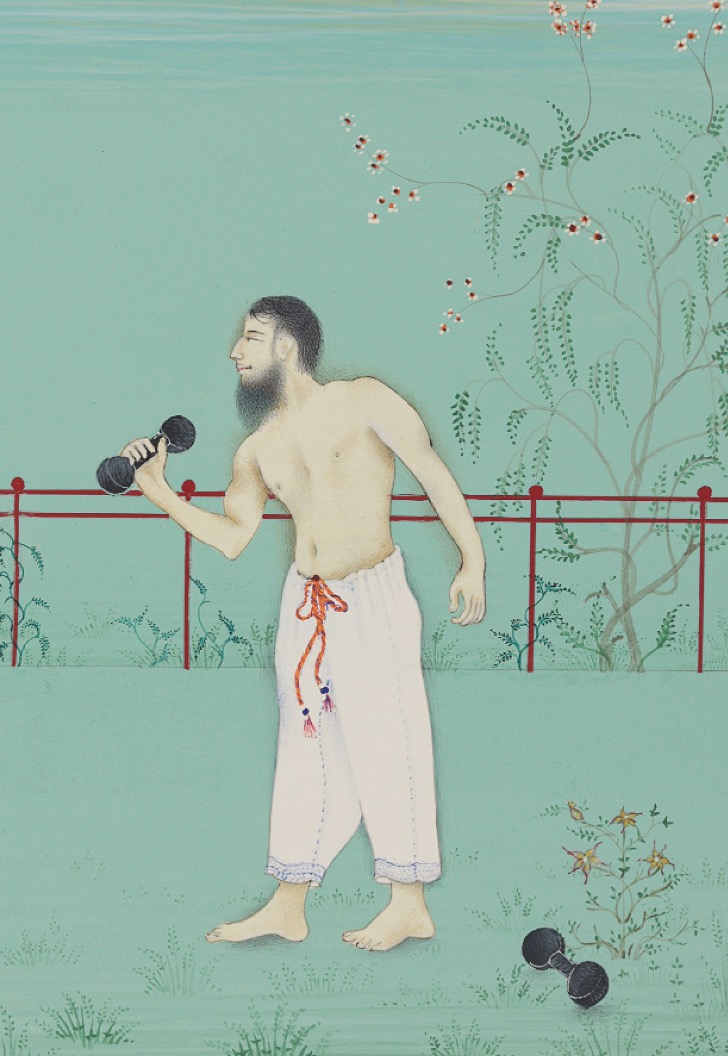

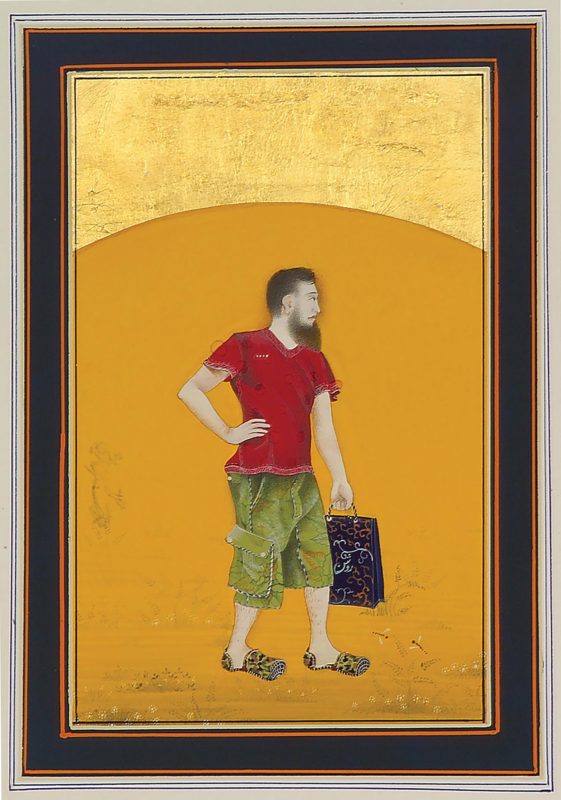

Today, Qureshi aspires to disrupt the illusion of the performative frame by the framing of stage, which later translated to the framing of narrative within his painted works, most notably his diminutive but mighty series entitled “Moderate Enlightenment.”

“Moderate Enlightenment”

“Moderate Enlightenment”

“I… represent bodies in a more abstract and performance-based way; at times there is no literal presence of a body but a strong sense of ‘someone’ in these works… the way I transform and stylize the figure and its background completely changes the original meaning. I am surprised when people describe me as a ‘figurative painter’. I would never categorize myself in that way. What is important for me is that the work has some kind of narrative, even if the imagery is completely abstract and non-figurative. I think perhaps this is due to my strong affiliation with miniature painting, in which storytelling is an essential element.”

“Every morning, since childhood, as soon as I wake up I read the newspaper. I have always been interested in my country and its politics and it’s a habit that has influenced my art practice. In 1990, on my first day at art school, there was a pile of chairs in the middle of the studio. Our professor, Salima Hashmi, asked us to draw it as a still life. Instead of choosing a white sheet of paper, like my classmates, I chose that day’s newspaper, which was full of news about unrest and agitations, and drew the piles of chairs on that.”

Qureshi’s approach to performance is almost Shakespearean: for him “all the world’s a stage” and it is this stage he presents, deconstructs, drops you into and then propels you to the edge of to consider larger narratives at play – most often in his sense of the birth and growth of this young country.

Talking about his shift in palette, Qureshi describes how “In 2009 and 2010, Lahore, where I live, was a main target for Al-Qaeda. There were bomb attacks almost twice a week. They destroyed the city. There was a blast near my house. I had very nostalgic connection to one place I used to go to with my wife, Aisha – a market that had been full of life. After this blast it was transformed into a bloody landscape. That was when I switched to using a blood-red tone.”

Eleanor Nairne of The Barbican described Qureshi’s recent show as an “epic distillation of labour… The works themselves speak of hours bent over an easel, executing tiny strokes with the customary squirrel-hair brush.” Amid the quiet labour, blood-red pigment and chaotic streaks intervene in otherwise serene compositions. Tiny, meticulous strokes of paint are applied with a gesture of magnitude. And as Qureshi’s mark-making spills out of the borders of pictorial space, onto the walls and the floor, we are surrounded by and immersed in the theatre of his painted world.

After winning the 2011 Sharjah Biennale for his breath-taking installation “Blessings Upon the Land of My Love,” Qureshi’s practice shifted in scale to a larger forum, beyond the borders of wasli. Any place became his ‘canvas’, from the rooftop of the Metropolitan Museum in New York to the nave of Truro Cathedral in England to a stone tower in medieval Sienna. The expanded canvas was both delicate and strident as opposites became reconciled in his work: violence and beauty, life and death, darkness and light. From the poetry of violence with its emotional scarring come the seeds of new life, of hope and a sense of boyhood wonder at beauty and the possibility of growth. In this way, Qureshi confronts people’s expectations of the jewel-like traditional Indian miniature, disrupting its visual field as people enter the work emotionally and physically and, walking on it, become embedded in the performance themselves.

Blessings Upon the Land of My Love

Blessings Upon the Land of My Love

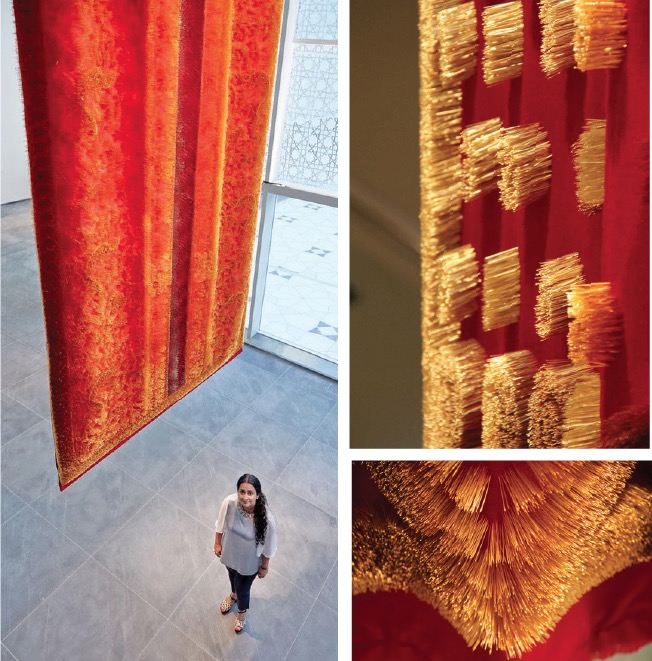

Aisha Khalid’s work is a celebration of beauty through the marriage of craft and concept. Her training in the miniature department at the NCA is similarly parsed with her traditional upbringing and an early encounter working with textiles as an activity that was solely the preserve of women at home. Khalid still works at home but home today is a state of the art minimalist space, replete with the old and the new, the traditional and the modern constantly at play with one another and designed by celebrated architect, Raza Ali Dada.

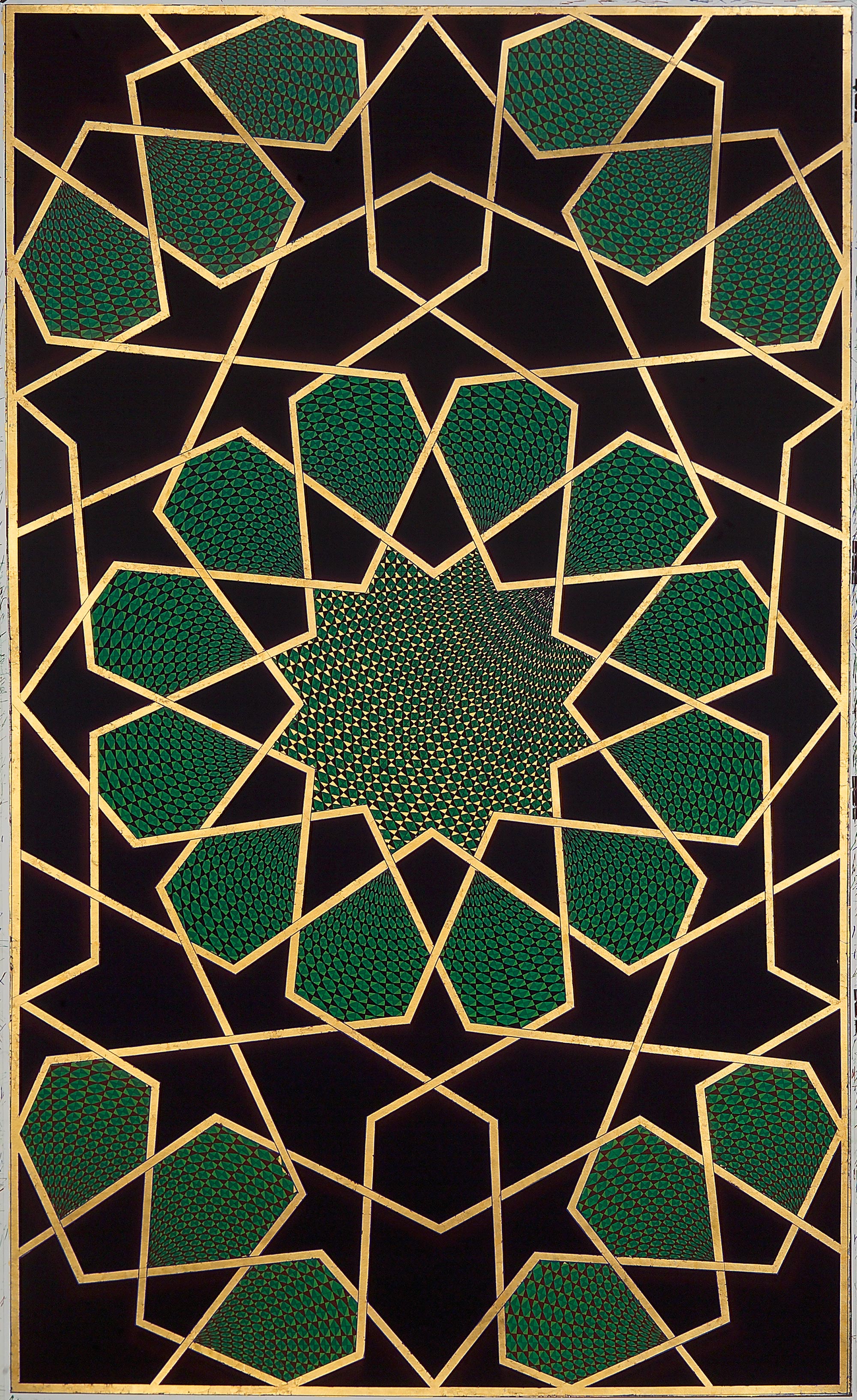

Khalid’s traditional upbringing has informed her reflections on the position of women in Pakistani society. The thing that constantly draws me to Khalid’s practice is the way in which I am seduced by beauty, by pattern and its satisfying symmetry. Yet the final statement is never declarative. Khalid upsets the apple cart by not subscribing to any one view. For me as a British-born Hindu woman of Indian descent, I find the ambiguity and nuance in Khalid’s hand utterly beguiling, full of sensitivity, complexity and richly riven with multiple layers of meaning. In Khalid’s painted world, the claustrophobia of an interior space is met with the unseen eyes of the veiled or camouflaged woman. Within her painted box, which has the illusions of a mathematical construction by Escher, a hidden female form is submerged becoming part of the fabric itself.

There is comfort in the order and symmetry of geometric patterning in Islamic art and at every turn, Khalid plays with pattern and with the social ordering of ritual. Ritual is in training the eye on pattern. Khalid finds refuge in this but even as she does, there is always an underlying narrative that serves to disrupt.

Aisha Khalid’s breath-taking 2009 “Kashmiri Shawl” is a seventy-foot hanging. The intricately hand-made traditional paisley pattern constructed with 300,000 gold-plated pins is suspended in a way that one can walk around it. For Khalid, the sharp pins symbolise the pain of the people in occupied Kashmir, from where her own ancestral roots originate. She took this process to a new scale with the 2015 work “Your Way Begins on the Other Side” created for the Agha Khan Museum in Toronto, a massive six metre long tapestry of 1.2million pins used to create an intricate pattern. On one side the pins protrude to form a silken carpet. On the other is a Persian carpet as the pinheads create outlines of a garden filled with animals. But we are beckoned not only to be seduced by the magnificent reference to the Mughal Garden, a recreation of Paradise on Earth, but to what lies behind, beneath and beyond.

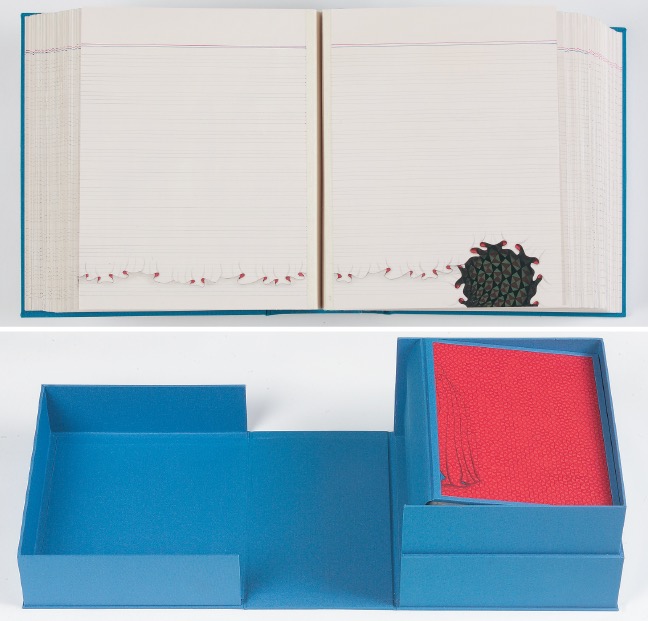

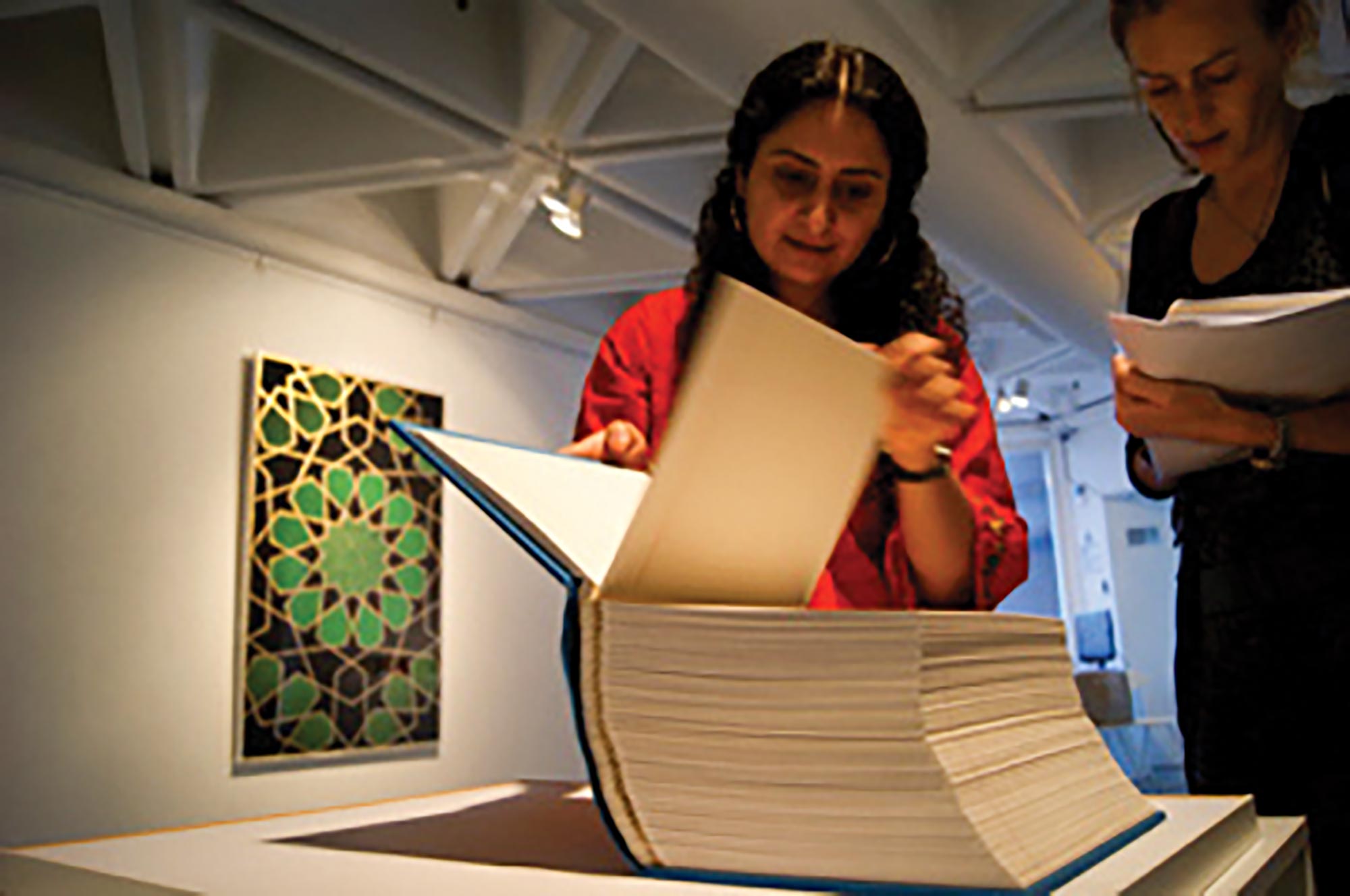

The 2009 work “Name, Class, Subject” is a trompe-l’oeil artist’s book inspired by the teaching aids used by government schools in Pakistan to teach writing in Urdu and English. Khalid meticulously crafted each one of the hundreds of pages to look exactly like a ruled exercise book. But there are ‘errors’ in the Urdu pages, reminders of the faults Khalid used to find in her own printed text-books as a girl, such as missing text and lines or badly cut margins. In the middle of the book both English and Urdu lines overlap and blur, a reference perhaps to Pakistan’s complex relationship with its own past and present. Everywhere in Khalid’s gentle oeuvre is the play between perception and reality.

Few ancient civilisations have so tenaciously preserved their traditions and an original facet of South Asian art is its conservative nature. Unlike the rejection of tradition at seminal moments in European modernism, South Asia’s modernist project was forged through a highly specific negotiation of its historic traditions, and not through the outright rejection of them. So what is the relationship to tradition and innovation, between the old and the new? Where does creative output find its best expression if not in the rejection of the past but rather in simultaneously accommodating and transforming it?

What is celebrated in both Khalid and Qureshi’s work is the act of making, its endeavour. The production itself is like a slow performance and our engagement with it is also part of the performance and life of the work. This is the brilliant marriage of craft and concept; two aspects often understood as diametrically opposed in the western world-view are, under the watchful guidance of these two, given an entirely new edge.

Qureshi and Khalid are not noisy and yet their work is pervaded with deep emotion, managing to carry powerful ideas without polemic. This is a kind of painted poetry and both have reclaimed (and transcended) the original function of Mughal miniatures as chronicles of contemporary social issues. The fact that Zahoor ul Akhlaq’s ‘revision’ of miniature painting came about as a result of his encounter with the collections of Indian painting held in the hallowed halls of the Victoria & Albert Museum and the British Museum, speaks to an East-West encounter that is still being explored and celebrated at the hands of both Khalid and Qureshi.

For me, Khalid and Qureshis’ worlds are replete with mirrors, whose reflection and refraction create a portal through which my emotions can travel, arrive, resonate and reverberate. They play with the edges, the borders and the frame of possibilities. They understand rasa.

It’s fashionable in museum circles of today to talk about the emotional landscape of the artwork like it is some kind of modern neuro-scientific discovery. But the landscape of emotion has always been integral to the arts of South Asia, which has postulated that the aesthetic experience rests not with the work of art, nor with the artist who created it but with the viewer. And it is the viewer that both Qureshi and Khalid place at the centre of their work creating intimate, proximate and intense exchanges.