Minar-e-Pakistan, a public monument commemorating the historic Lahore Resolution, is one of Pakistan’s most well-recognized landmarks. Yet little is known about the man responsible for its design and construction, a man whose story goes beyond the minar, and far beyond Pakistan. Journalist Sonya Rehman uncovers the legacy of a true visionary who is only now getting the credit that he deserves.

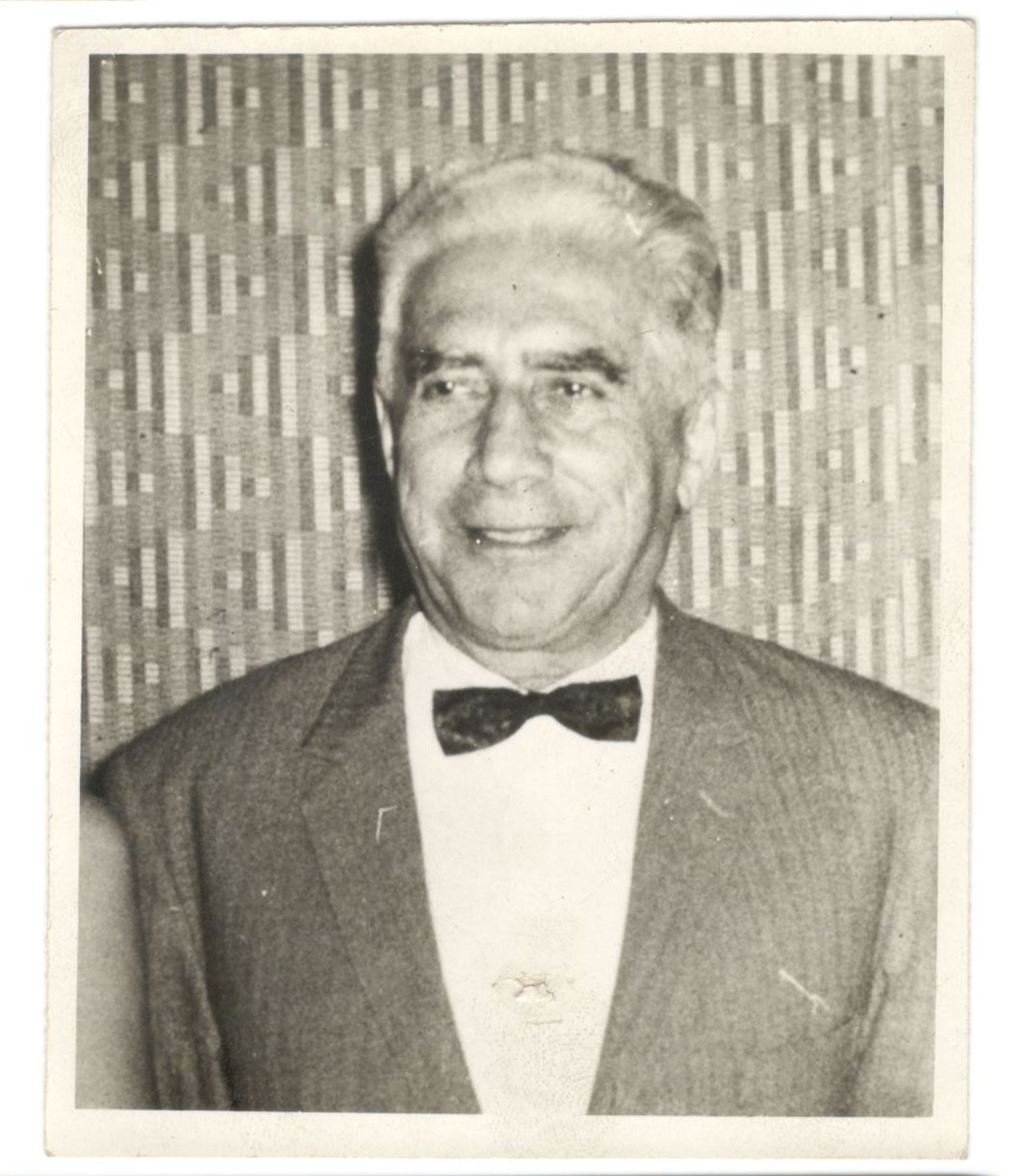

He wasn’t ordinary, and neither was his life. Even though Nasreddin Murat-Khan is largely acknowledged as the ‘architect behind Minar-e-Pakistan,’ his story goes beyond the minar (tower), and far beyond Pakistan.

He wasn’t ordinary, and neither was his life. Even though Nasreddin Murat-Khan is largely acknowledged as the ‘architect behind Minar-e-Pakistan,’ his story goes beyond the minar (tower), and far beyond Pakistan.

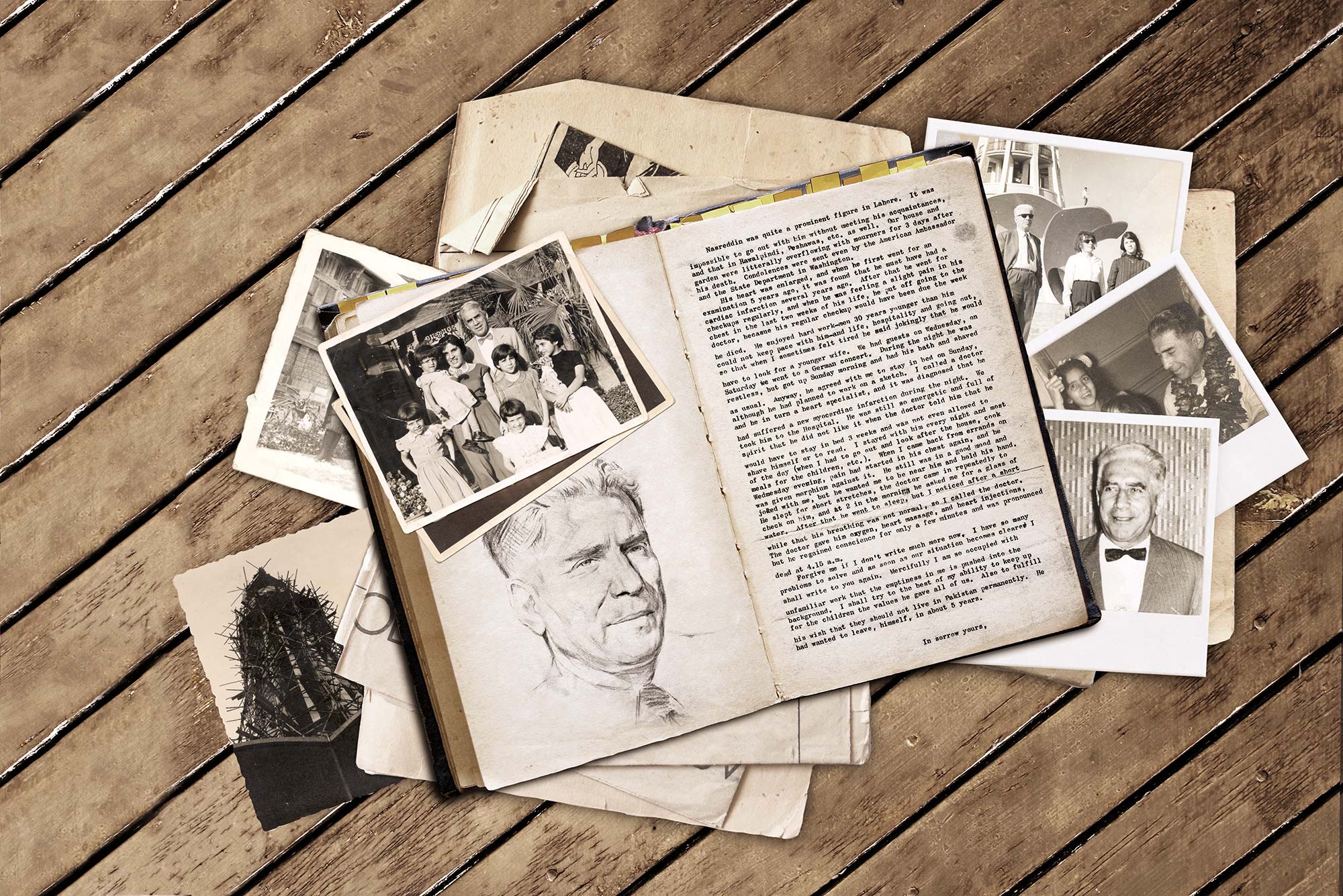

We meet at her childhood friend’s home in Lahore for tea. Meral Murat-Khan, Murat-Khan’s youngest daughter, is soft-spoken and candid as she narrates her beloved father’s journey from Daghestan, Russia, to Lahore, Pakistan.

Born in Daghestan in 1904 to a father who was an Imperial Russian Army officer and a mother who died when Murat-Khan and his siblings (a brother and a younger sister) were very young, Murat-Khan and his family, Meral tells me, were deeply involved in the resistance movement to free the Caucasus from the then USSR; a movement that first began as the Caucasian War, led by Imam Shamil in the 18th century against the Tzar-controlled Russian Empire.

Graduating with triple degrees in architecture, civil engineering and town planning from the Leningrad State University (now known as the Saint Petersburg State University) in 1930, Murat-Khan enjoyed a thoroughly successful career in the capacity of both a chief civil engineer and chief architect involved in a number of projects in the former USSR, such as the national theatre in the city of Derbent (for which he won first prize), a polytechnic institute for 800 students in Makhachkala (the capital city of Daghestan), a 600-bed general hospital (in Makhachkala), town planning and designing for a new township of 60,000 families in Makhachkala, a V.J. Lenin memorial and numerous other projects.

However, due to his involvement in the movement, Murat-Khan had to flee Daghestan with the German retreating army for fear of his life between the years 1943-1944. “He had to leave,” Meral states. “Forty members of his family were massacred right before his eyes. He lost everything.”

While his brother was sent to Siberia (due to their entire family being blacklisted), Murat-Khan’s sister immigrated to Iran.

“It was a very hard, painful time for him. I remember as a child I used to try and pester him to tell me stories of his life in Daghestan but he’d never talk about it, except he did tell me about how proud he was of his heritage. He used to say people in his village would rather commit suicide than give in – they were a very close-knit, proud community. Even if it meant an entire family destroying themselves, they would never surrender.”

After escaping from Daghestan in 1944, Murat-Khan’s life changed drastically: from a thriving career in Russia, he now lived as a refugee in a camp run by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), in Berlin, Germany.

But it was here, at the refugee camp – where Murat-Khan worked as a camp engineer and chief architect – that he met the love of his life: Hamida Akmut, a Turkish national refugee.

Half Austrian and half Pakistani, Hamida was studying to become a doctor when Vienna was invaded by Russia. While her parents were settled in Turkey, Hamida, like Khan, became a refugee, working in the camp as a nurse since she couldn’t complete her degree (given the political climate at the time).

Coincidentally, both Murat-Khan and Hamida had adjoining cabins at the camp. “I think it was love at first sight. She used to say it was his voice that she fell in love with,” Meral laughs. “They wanted to get married within three weeks of meeting!”

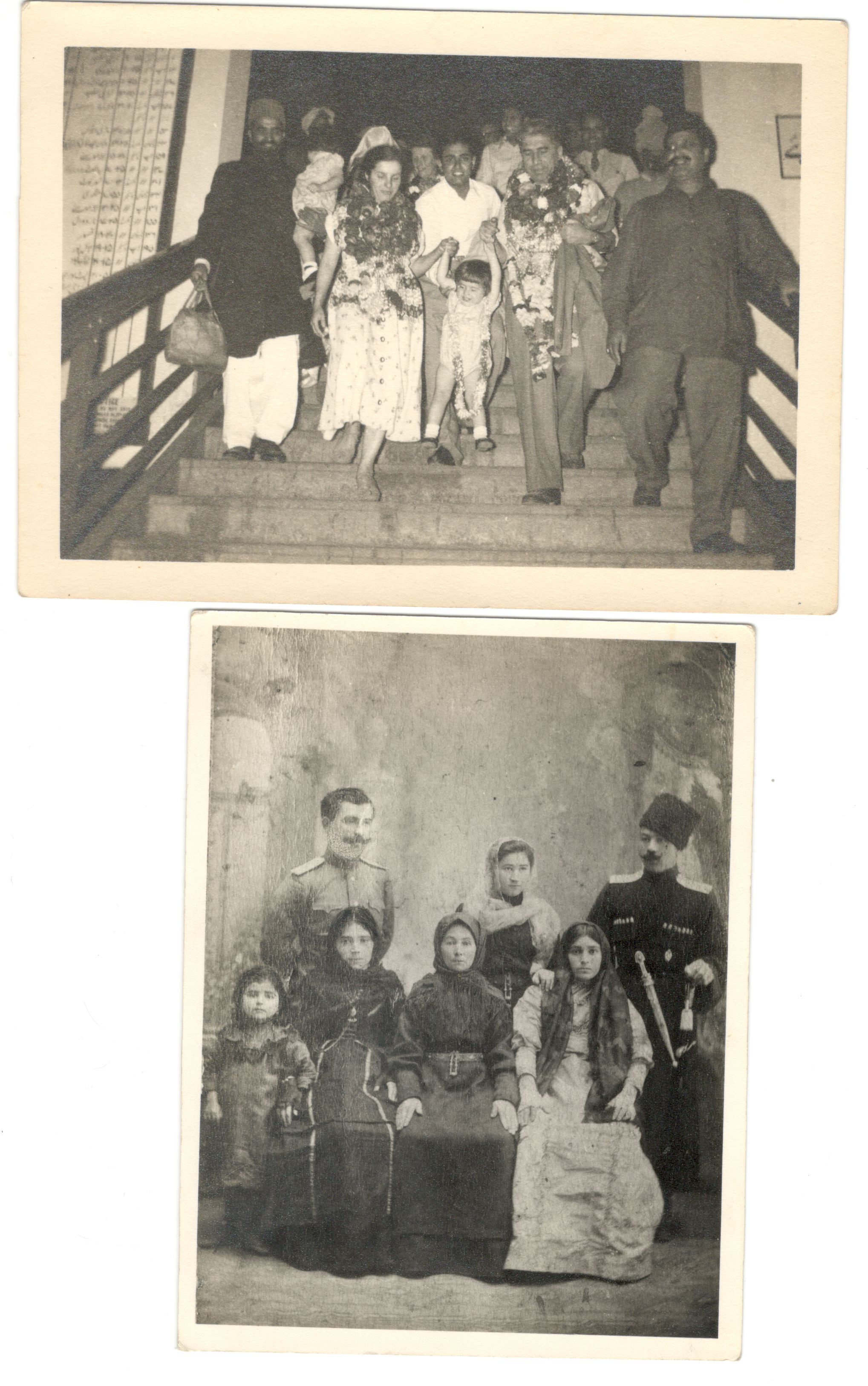

Not long after, the young couple decided to migrate to Pakistan since the UNRAA camps were shutting down. Without a country to call their own, Meral states that the decision to shift to Pakistan was partly due to the fact that her mother had family in Pakistan (Hamida’s father was Pakistani).

Arriving in the country in 1950, thus began a new path in Khan’s life; a path which would eventually lead him to single-handedly make one of the largest and most iconic monuments in Pakistan.

“Initially it was very difficult for them to settle in,” Meral states, speaking about the early years of her parents’ move to Pakistan. “They had to start from scratch because they were coming into an environment which was completely alien to them.”

But after a few years of getting their bearings, Khan began working for the Pakistan Public Works Department (PWD) for a few years before launching his very own architecture firm in 1959 by the name of Illeri N. Murat Khan & Associates.

But after a few years of getting their bearings, Khan began working for the Pakistan Public Works Department (PWD) for a few years before launching his very own architecture firm in 1959 by the name of Illeri N. Murat Khan & Associates.

Residing in a beautiful, picturesque home on Montgomery Road (on Mall Road) in Lahore, Murat-Khan, with his wife and five daughters (Pari, Zeynab, Maryam, Mesme and Meral), lived a stable and happy life.

“We always had an open house where guests came and went,” Meral reminisces fondly. “My mother was always in the kitchen concocting meals because we had visitors all the time.”

A devoted, gentle father who, Meral mentions, “had a great sense of humour,” Murat-Khan was a caring man who was utterly crazy about his girls.

“We were such a mix; neither Pakistani nor European, it’s amazing my parents created that cocoon for my sisters and I,” says Meral. “Both of them had suffered, but they managed to create a home for not just us but for everyone who knew us.”

In the eleven years of his prolific private practice, Murat-Khan designed countless residences (in Lahore, Islamabad, Rawalpindi, Peshawar and Gujranwala), in addition to a number of town planning schemes (the WAPDA residential colony at Mangla Dam, Lahore and Multan), hospitals and clinics (the 1000-bed Nishtar Medical Hospital in Multan, a mental hospital in Mansehra for 500 patients), educational institutions (the Divisional Public High School in Faisalabad, Divisional Public High School in Lahore, an auditorium for a 700+ seating capacity at the Forman Christian College in Lahore), mosques (at the Governor’s House in Lahore, the Jamia Mosque in Mirpur), WAPDA residential flats in Lahore, a library and ladies park in Rahim Yar Khan, the Bank of America in Lahore, Fortress Stadium and Gaddafi Stadium (both in Lahore), the Municipal Office in Multan, a shopping centre in Peshawar and several others, too many to list.

For his outstanding service to the country, President Ayub Khan honoured Murat-Khan with the Tamgha-i-Imtiaz (Medal of Excellence) in 1963.

Yet, speaking about the minar, Murat-Khan’s youngest daughter is pained. “He spent ten years on that project and never charged a penny for it,” Meral states, “He said that he was making the minar as a contribution to the country which gave him a new home.”

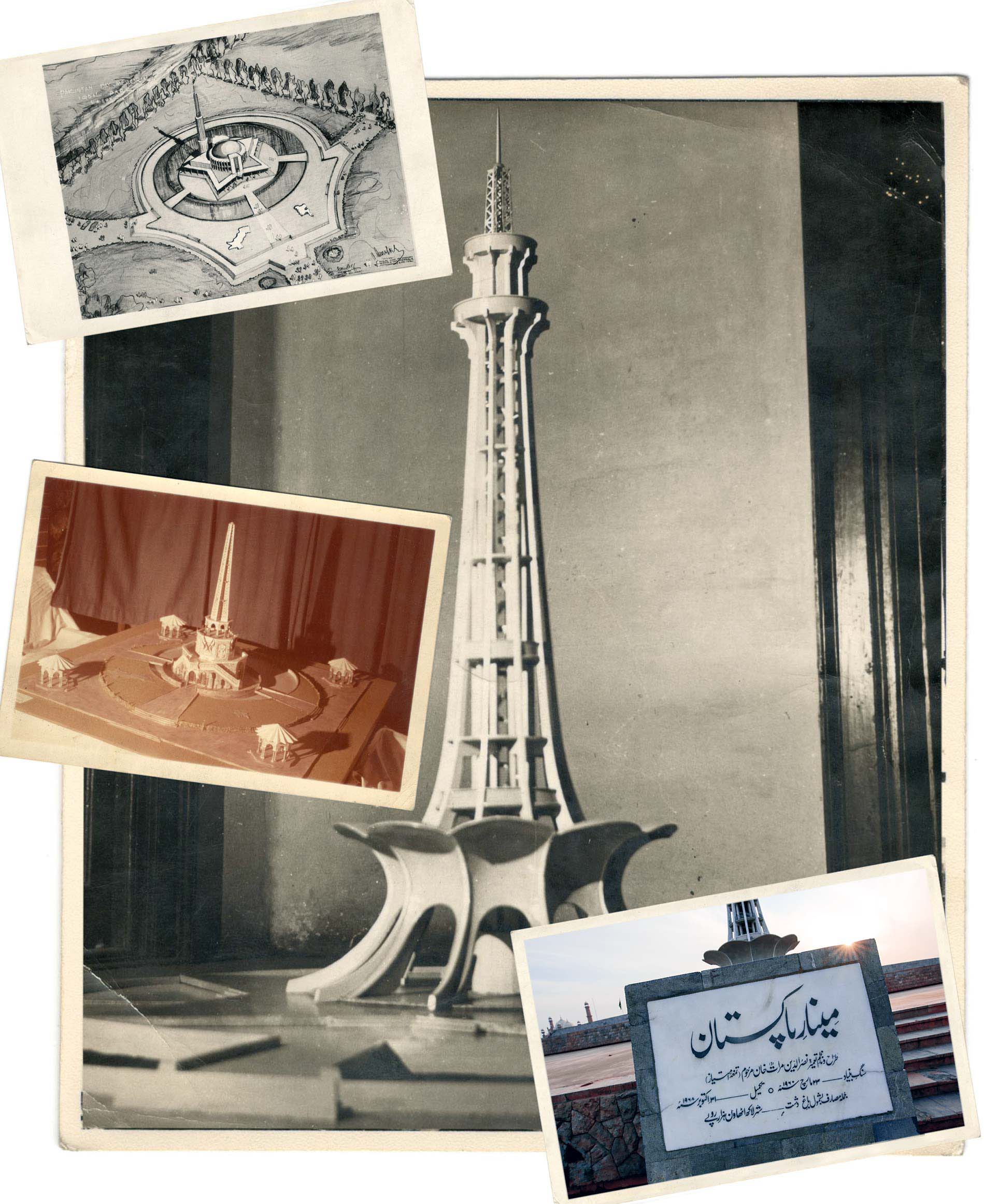

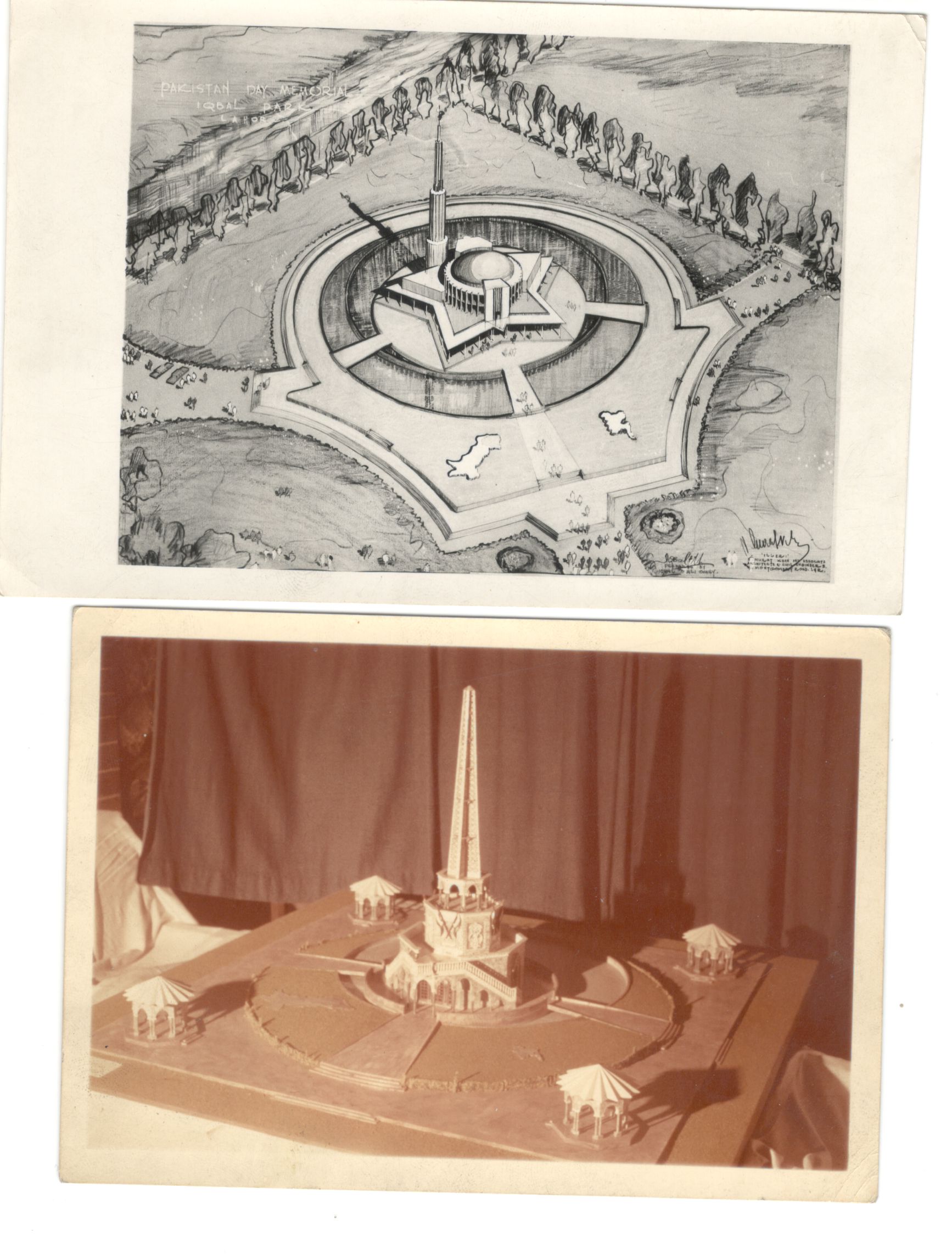

Invited by the government of Pakistan to submit a few preliminary designs of the minar, Murat-Khan began formally working on the monument’s construction in 1959.

To be built in an area (Iqbal Park) where the historic Lahore Resolution was passed on the 23rd of March, 1940, the architect’s original design portrayed the minar without a covering. Why? To signify a young country’s infinite, promising growth.

However, Meral states that her father was asked to cap the minar with a dome as the committee didn’t find the design of the dome-less structure “Islamic enough.”

“He told them you’re stunting the growth, but they insisted on the dome,” Meral says. “Right from the very beginning, from what I remember, there were squabbles. My father was a man of great integrity; he refused to allow any dishonesty,” she says, mentioning that this irked certain committee members who then sent Murat-Khan a letter thanking him for his services, and maliciously ousting him from the project a month before the monument was to be officially inaugurated.

Meral further reveals that the building committee then took over the building site without her father’s consent, disallowing him from overseeing the last few weeks of the minar’s completion, and sent him the final bill for an approval.

Murat-Khan rejected the bill. The defects had to be verified, corrected and removed. Only then would he allow the final bill to be passed.

But the committee didn’t budge and eventually went ahead with the launch, not having the courtesy of inviting Murat-Khan to the inauguration.

“He was very heartbroken,” Meral states. In fact, so devastated was Murat-Khan that he decided to leave the country with his family for good.

However, exactly one year after the completion of the minar, Murat-Khan died of a sudden heart attack. It was 1970 and Meral was only fourteen-years-old when she lost her father.

“It was the final nail in the coffin,” she says, alluding to the fact that her father did indeed die of a broken heart.

In the years that followed, Meral made it her life’s mission to correct the grave misconception (in the press and online) that her father was only the architect of the minar.

“He was both the architect and the engineer – I’ve been fighting to resolve this inaccuracy for fifteen years; but there’s so much misinformation out there, the facts are continuously presented inaccurately… besides, the plaque which mentions my father’s name at the base of the minar doesn’t mention anything about his background, his story.”

“He was both the architect and the engineer – I’ve been fighting to resolve this inaccuracy for fifteen years; but there’s so much misinformation out there, the facts are continuously presented inaccurately… besides, the plaque which mentions my father’s name at the base of the minar doesn’t mention anything about his background, his story.”

“I don’t want any publicity for myself,” Meral says, her voice choking with emotion. “This is why I didn’t really pursue to fix it for a long time, but when you keep reading about how the engineer of the minar was someone else, it hurts immensely.”

A few weeks after meeting Meral, my phone lit up with an SMS from her bearing good news: a brand new, detailed plaque on Murat-Khan was finally approved and placed on the monument thanks to a go-ahead from a man called Mian Shakeel, the Director General at the Parks & Horticulture Authority (PHA) in Lahore.

In the message, Meral sounded thrilled, but more than that, her sense of relief was tangible.

Finally, her father, Nasreddin Murat-Khan, an unsung national hero, would get the credit that he so rightly deserved.

Maryam Murat-Khan

“I remember Papa as a perfectionist and someone who would stick to his principles; one time I failed my Urdu dictation in class and the teacher called me stupid and slapped me in front of the whole class. I went home and told Mum and Papa, and he went back to the convent school and told Mother Andrew that no one had a right to slap us. He said he didn’t slap his kids and so no one else had the right to slap them. The teacher (I can’t remember her name) never dared yell at me again.

[Papa] would also play tricks on us, he tied my braids to the chair once, and I couldn’t get up.

Also, when I was really young and decided to ‘help’ him by drawing all over his plans, he didn’t yell, as he understood it wasn’t deliberate bad behaviour.

Also when Chippy (our squirrel) got into his detailed house plans and chewed them up, he was mad, but didn’t make us give him up as he knew we loved Chippy.”

Mesme Tomason

“I used to go along with my father when he went to the fruit bazaar on Sundays. My sisters did not want to go along, especially in the summers but I loved it. I would skip along or almost run because Papa walked so fast and expected me to keep up with him. He let me pick out some of the fruit, so I picked my favourites of course.

Growing up with an architect and civil engineer taught me many things. I would draw and take my drawings to Papa to give me some pointers… he would end up drawing over to make the improvements. For some kids, this may have been discouraging, but to me, it always encouraged me to do better.

Papa would also take us along to building sites. While the Minar-e-Pakistan was under construction, we loved to go along and play in the piles of raw materials. I would walk up the spiral staircase that was being built a few steps at a time, and I remember one time he got very upset because I was about half way up and standing on the last step that had a sheer drop. Needless to say, I was not allowed to go up that far again until the entire staircase was completed.

Papa travelled to sites away from home and frequently would bring little presents back for his ‘girls.’ One time, he brought us a cute little lamb; another time he brought home a couple of bunnies.

Papa liked to try growing different kinds of vegetables and fruit. The gardener would make sure he followed direction on how to take care of them and we would have freshly picked veggies for our salads, etc. We entertained many different dignitaries and clients at home. One time he pulled a joke on a client friend of his. We had a plate of fresh radish from our garden, both red and white ones. He cut a horseradish (very spicy) and added it to the plate. We kids knew that horseradish was a creamy colour and the white radish was a little translucent white. He offered his guest some. The guest, knowing my dad’s propensity for playing jokes, asked one of us to eat one to see if it was okay. One of my sisters took a slice of white radish and finished it off. Now the client took a slice, not realizing that my dad had turned the plate so that the first thing he picked was a horse radish… poor man, his eyes teared up as he tried to finish the bite without spitting it out!”

Comments are closed.