Nick Merriman is the Director of the Manchester Museum, UK’s largest university museum. His background as an archeologist and heritage expert has seen him take on numerous projects centered around the themes of cultural diversity and sustainability, the most recent of these being ‘New North South’, a partnership of ten arts organizations in the UK and South Asia that seeks to promote deeper understanding between the regions. While recently in Pakistan, Nick chatted with Team Destinations about why Pakistani contemporary art is taking the world by storm, the historical ties that bind Manchester and Pakistan, and how Lahore turned out to be a city of surprises.

The Manchester Museum will soon be home to a permanent South Asia gallery, set to open in early 2020. Why did the museum feel the need to create a separate gallery dedicated to the region?

The starting point for the idea a gallery dedicated to the history and culture of South Asia at the museum came about from a realization that 13 percent of the city’s population is of South Asian heritage, and most of those are of Pakistani origin. Yet we don’t see South Asian visitors to our museums and galleries in that proportion – only about 4 percent of the museum’s visitors are of South Asian origin. We realized we were obviously missing something; there was no narrative anywhere for the history of South Asia in Manchester. Manchester Museum is a museum of human and natural history; and we have very little material from South Asia.

To cut a long story short, we entered into a partnership with British Museum to create this space, which will be the largest single gallery in the museum. It will tell a pretty comprehensive story of South Asia from early human settlements to empires like Asoka’s to the British Empire. Crucially, it will be the first gallery to tell the story of migration from South Asia to the UK.

The city of Manchester is also celebrating contemporary South Asian art at the moment, under the expansive New North South project, for which you serve as the lead spokesperson. Can you tell us more?

We wanted to do something to mark the 70th anniversary of the independence of Pakistan and India and also to celebrate the shared heritage of the North of England and South Asia. New North South is a three-year programme that focuses on the contemporary art scene in South Asia – by which I mean Pakistan, Bangladesh, India and Sri Lanka. It hopes to reimagine the relationship between the North of England and South Asia on a more equitable basis than the historic ties. It’s a partnership between 10 different organizations facilitated by the British Council; 5 in the North of England, namely the Manchester Museum, Manchester Art Gallery and Whitworth Art Gallery in Manchester, the Liverpool Biennial and The Tetley in Leeds, and 5 in South Asia, which are the Lahore and Karachi Bienniales, Colombo Biennale, Kochi Biennale and the Dhaka Art Summit.

Other than engaging with the city’s substantial South Asian population, does the project also intend to reshape the UK’s general perception of what it means to be South Asian?

One of the main aims of my museum is to promote understanding between cultures by showing a different image of South Asia, based around its creativity, its dynamism and its variety. Through the New North South, we are trying to mainstream South Asian art; and the ultimate aim is to make it unremarkable in that it ceases to matter where it comes from.

During the opening weekend, 6 shows opened at the Manchester Art Gallery, out of which 4 were by Pakistani artists, including Waqas Khan, Risham Syed and Mehreen Murtaza. Some of the anecdotal feedback we’ve received from audiences so far is that they are just amazed at the dynamism of the works, and the fact that these artists are no different from artists anywhere else in the world; that they are not necessarily defined by their background but are defined by their humanity.

Can you cite any one particular show/performance/installation that perfectly captures the aim of New North South?

Nikhil Chopra is a performance artist from India and I particularly liked the story that his work encompassed. He put up a non-stop, 48-hour performance at the Museum of Science and Industry based around a steam locomotive that he discovered there. It was built in Manchester for the North West Indian Railway and then transferred to Pakistan around the time of partition. It still has these giant initials on it – ‘PR’ for Pakistan Railways. It was one of those locomotives that was most certainly bringing people to safety, to Pakistan, during partition. Nikhil adopted different personas during the performance and drew on canvas. His father, who grew up in Lahore, was also involved, and it was a really moving piece. It encapsulated a lot of things we wanted to do – it was prompted by the 70th anniversary of the partition, it linked Manchester to South Asia, it showed a great artist at the peak of his power and told a story that was easy to relate to for non-traditional audiences.

What was the process of choosing the artists who became a part of the project?

A whole team of us from North England made various visits to the region and saw that there is so much going on here that doesn’t get exposure in the UK. The aim was to find artists who are mid career, and who really deserve international recognition. There was no one theme we were looking for; the selection was based on the quality of their art, its excellence and innovation.

One of the stand-outs for me has been Waqas Khan from Lahore. His work is so amazing in its minute detail, with its swirling organic shapes based on biology and Sufi philosophy. It is abstract work, but it’s very moving in a way that’s almost inexplicable. Waqas’ show received 5-star reviews from the UK press and he was announced as a major international artist. That’s what we want – to find someone who is really good and give them a platform.

This is your second visit to Pakistan in less than a year. You work closely with the South Asian community in Manchester and now that you’ve been to Pakistan twice, do you feel you have a better understanding of the country, the art coming out of it and the context in which it is being produced?

I was conscious that I was working in partnership with the Karachi and Lahore Biennales and I had never been to Pakistan. I felt I couldn’t understand how to work with the organizations unless I had been there. Also, there is no substitute to meeting people face to face. During my first visit in February, I spent a few days in Lahore being wonderfully hosted by members of the Lahore Biennale and visiting quite a few artist studios.

There had been a bomb incident just before my visit, so there was some nervousness on behalf of the hosts about letting me wander around. Colleagues in England kept asking me if I was really going to go as it was very dangerous. The timing actually turned out to be very salutary because after the Manchester Arena bomb this year, some of our colleagues from South Asia were worried about coming to Manchester. I think the trip was really good for mutual understanding. When you come to a city, you realize that for the vast majority of people, it’s just normal life despite the rare terrible incident.

After the two visits, I could also understand the context of doing a biennale here in Lahore and Karachi where so much of the budget is spent on security and then on electricity generators. These are the kind of things that one doesn’t think about in the UK and it is very important to understand the context in which people who you work with are operating.

What are your impressions of Lahore?

The first time around, security was heightened so I spent most of my time inside a car. I did go to Old Lahore, which as I expected was full of narrow alleys bustling with life, similar to some of the older cities in other parts of South Asia. What I didn’t appreciate until this second visit is what a lively, modern, cosmopolitan city Lahore is, and what a young population it’s got. I’ve had really excellent quality international food and where we’re in right now is a lovely little coffee shop, the kind that I’d expect to see in any major city of the world.

What’s really struck me is how vibrant the art scene is and how much creativity there is. I’m not just talking about visual arts, I see it in architecture, in fashion, in craft as well. In that sense Lahore has confounded my expectations because its image perhaps is more of an older city but it’s got the old and the new working very well alongside each other.

This time around, you’ve come as a delegate of the Heritage Now Festival, an event aimed at discussing issues that face museums and the heritage sector in Pakistan. What do you think are some of the major challenges that Pakistan has to confront in that area?

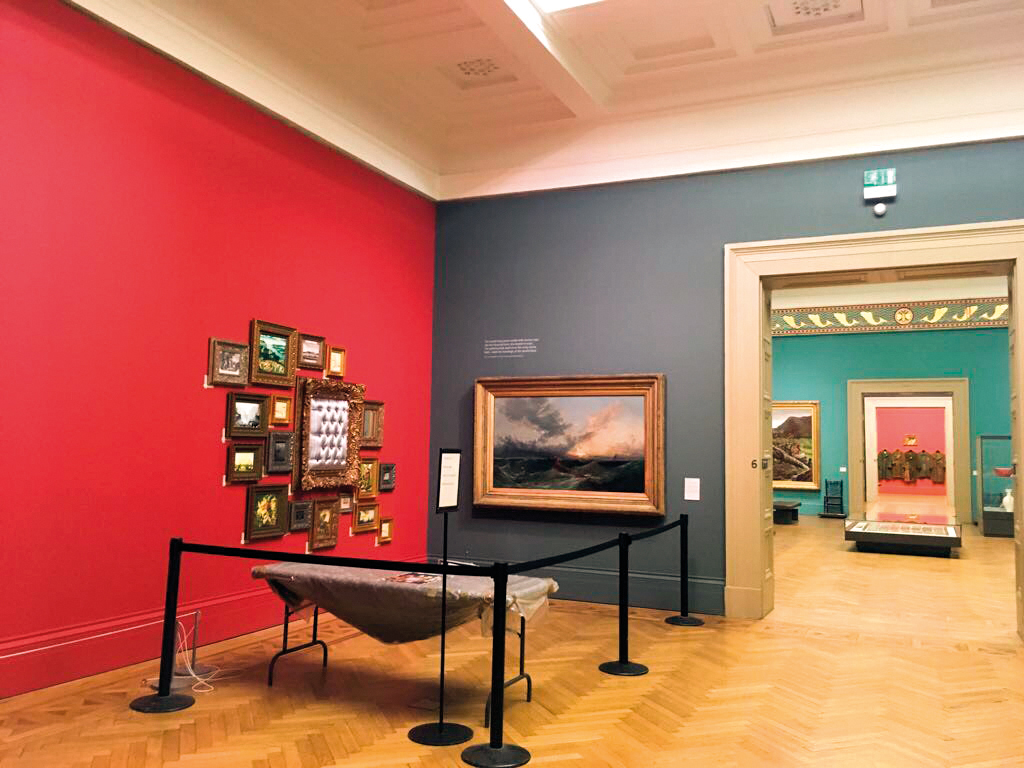

The heritage of Lahore is absolutely fantastic but as with many heritage cities, there is a real challenge as to how you preserve, conserve and make accessible that heritage for contemporary audiences. I hope the seminar will get some momentum behind a new heritage strategy for Lahore that will see the Walled City being looked after and made accessible to wider audiences. Similarly, the Lahore Museum is a fabulous building with a fantastic collection that needs investment to bring it up and make it attractive for contemporary audiences.

Museums are incredibly popular in the UK at the moment, and that is a result of 25 years of hard work. Most of them, including the big national museums, are free of charge. At the Manchester Museum, we have really worked at making ourselves accessible through our programming, through the welcome you get when you come in and you see people like you. To get to this point, Pakistan requires investment in buildings and staff and that’s the next big challenge facing the country and its heritage sector.

This is an exciting time for art in Pakistan, poised as we are between the Karachi and the Lahore Biennale. What are your hopes from the two international art events?

What I’m really hoping for is that they will put Pakistani art properly on the international map. More importantly, within Pakistan where the audience for contemporary art is perhaps not as large as it could be, they will show a different way of engaging people with art – in a more fast-moving, non-traditional world outside of building-based institutions; in spaces where ordinary people would feel comfortable going. What’s fantastic is that two biennales are working to showcase the dynamism and sheer variety that exists in the art scene here in Pakistan