Travel writer and historian Salman Rashid narrates a fascinating account of the history of Bahawalpur, from the times of the Rajput prince in the 10th century who laid the foundations of the mighty Derawar Fort in the Cholistan Desert to the reign of the descendants of the Abbasid caliphate who became the founders of this vastly affluent state.

The river Jamuna was home to a fearsome dragon in an age long ago. For some reason the gods became displeased with it and ordered it to leave the river and seek a new home in the vast oceans. But because the dragon could only travel through water, the gods were benevolent enough to order the Jamuna to send a stream southward all the way to the sea.

The dragon left the river by this new stream that was for millennia known as the Hakra. But the long and creative passage of time leaves nothing, not even the work of gods, unaltered. The Hakra that was once the dragon’s passage and which slaked a huge country turning it green with farmland and orchard dried up. The land turned desert and today the only sign of the lost river is a meandering depression through the dunes of the Cholistan Desert.

Here, amid the dunes-hardy desert, Rajputs continued to worship Dharti Mata, the Earth Goddess, whose echoes we still hear at the festival of Channan Pir near Yazman. And here the crafty prince Rawal Deo Raj carved out a kingdom for himself. Given a cowhide by his father-in-law and told to build his territory on an area that could be covered by it and no more, the astute prince did not have to think long. Cutting the hide into thin strips, he compassed a large area that his father-in-law could not deny him.

On that he raised his mud-brick fort calling it Dera (home) Rawal Deo Raj after himself. That was in the middle years of the 10th century. Over time it came to be known as Derarawal or Derawar and as its hoariness grew, legends accreted to it. Among others, it was believed to be the repository of a vast treasure left behind by Alexander the Macedonian as he passed on southward through this territory.

Drawn by these stories, Shah Hasan Arghun, then ruling over Sindh, raided Derawar in 1525. His history refers to the fort as Dilawar and we are told that after a short siege, he defeated the Langah chieftain and removed a large treasure from the fort.

The truth sprinkled across the dunes of modern Bahawalpur district in the form of cultural mounds is that the Hakra did indeed flow and nurture an ancient civilisation whose cities easily rivalled the better-known Moen jo Daro and Harappa in the Indus Valley. The truth also is that some four thousand years ago, the Hakra ran dry. The inhabitants of its rich cities moved away and the sand moved in to smother their homes. While the Indus Valley received the archaeologists’ fullest attention, the lost Hakra remained a poor cousin and was only cursorily investigated so that we do not know what surprises still sleep beneath the Cholistan dunes.

This silence, broken periodically, prevailed for centuries until far away in the south a squabble broke out between brothers. Amir Channi Khan, holding sway in upper Sindh, had on his deathbed passed on his turban, the symbol of government, to his elder son Mehdi. To the younger Daud he bequeathed his copy of the Quran and his rosary to take on the role of spiritual guide. Some years later when Mehdi died, Daud Khan attempted to deprive Mehdi’s son, his own nephew, Kalhora of the turban. Bitter strife ensued until Daud abandoned his claim to the throne and migrated north to stake out another area.

Known as the Daudpotra (sons of Daud), surnamed Abbasis for they claimed descent from the Abbasid caliphate, this man’s progeny became the founders of a state that was so affluent in the 20th century that besides doing great public works in its own domain it also financially supported the municipal uplift of Mecca. The first Abbasi to come into prominence was Sadiq Mohammad Khan I in the 1730s. He was an administrator who subdued local brigands to bring peace and order and built towns in the country today known as Rahim Yar Khan and Bahawalpur.

Seeing his ability, the Persian invader Nadir Shah placed him in charge of the important towns of upper Sindh together with the ancient fort of Derawar. This latter place, Sadiq Mohammad had only a few years earlier wrested from the Rajput prince Rawal Akhi Singh. But Sadiq Mohammad’s days were numbered.

As soon as Nadir Shah had withdrawn to the west, Sadiq’s kinsman Khudayar Kalhora attacked him in his Shikarpur stronghold. A hard fought battle resulted in the death of Sadiq and his turban passing to his eldest son Bahawal Khan I. Realising that he did not possess the wherewithal to hold a country extending as far south as Shikarpur and Larkana, Bahawal Khan turned his attention to a spot way off in the north.

In the sandy wilderness, a few kilometres from the banks of the Sutlej River, stood the solitary mansion of a local zamindar. Raising a fortified wall around it and establishing a town within, Bahawal Khan called it Bahawalpur after himself. So that verdure may replace desert aridity, he ordered a canal to convey water from the Sutlej and along its serpentine course he planted gardens. The year was 1748.

Sixty years later, in 1808, the peripatetic statesman and writer Mountstuart Elphinstone came to Bahawalpur. The walls enclosed a town of about ‘4 miles in circumference’ where mango orchards grew amid tightly packed houses. He found the streets crowded with townsfolk who had a language distinct from that of central India and a particular mode of dress. The man also noted that industry thrived and cotton lungis and silk girdles and turbans were the major manufacture of Bahawalpur.

Fast forward to 1827 and we have Charles Masson, the scholarly deserter from the East India Company army travelling about under a pseudonym to escape arrest and court-martial. He was delighted to reach Bahawalpur after the long journey through sandy wastes to find himself ‘in a large populous city, surrounded with luxuriantly cultivated fields, and groves of stately palm-trees.’

Bahawal Khan’s canal that he called Khanwah and which was commonly known as Nagini – serpentine – because of its meandering course had worked wonders for the city: Masson found it a place of ‘fertility and abundance.’ The wall was gone however, for the ex-soldier noticed but traces of it.

Time passed and one thing that stood out was that the Abbasi rulers of Bahawalpur treated their fiefdom with great concern and an eye for progress. By the end of the 19th century, the town was a bustling mart with a brisk trade in cotton, indigo, oil seeds, dates, mango, livestock, carpets and leather products. Travellers of a hundred years ago noticed narrow bazaars roofed with matting to keep the heat out and thronging with buyers and sellers engaged in animated trade. By every measure, Bahawalpur was a success story.

This progress is remarkable in view of the disturbances of the 1860s during the reign of Nawab Bahawal Khan IV (reigned 1858-1866). The Nawab’s own kinsmen, colluding with some Baloch chieftains, planned to replace him with an uncle of his. On 27 March 1866, the Nawab was served a poisoned meal and before the night was over, he had given up his ghost.

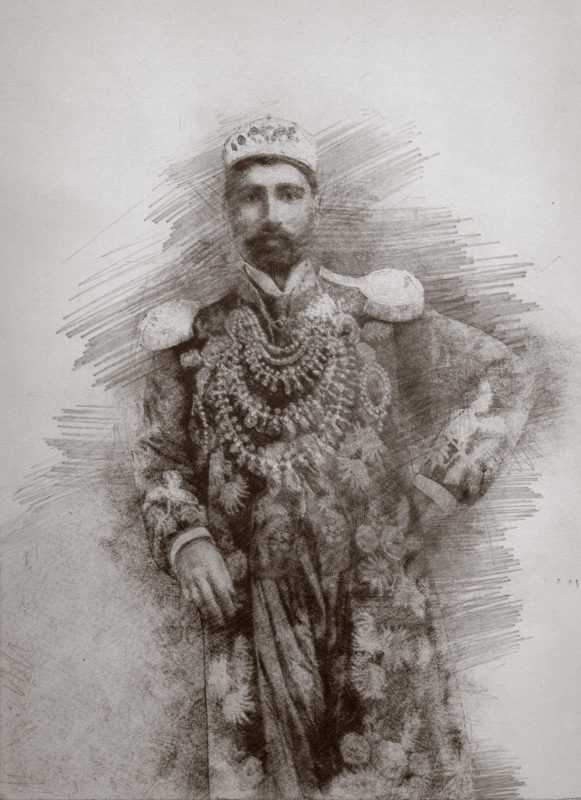

His son, Sadiq, not yet five years of age, was named the next Nawab. It was a time of great uncertainty as his dowager mother fended off the intrigues of courtiers and pretenders to the throne. At eighteen he received the turban and became the ruler of Bahawalpur as Sadiq Mohammad Khan Abbasi IV. He was a man cultivated and possessed of fine taste. In the annals of Bahawalpur, he can easily be celebrated as the finest builder who set the tone of the building tradition among his successors.

1866 – 1899

In 1874, Sadiq Abbasi ordered the fabulous Noor Mahal to serve as his private residence. When it was completed the following year, his treasury was the poorer by Rs. 1.2 million, but the city of Bahawalpur had gained a jewel that it can still be proud of. With its domes, pillared verandas and pediments, it is a masterpiece of Italian architecture in our part of the subcontinent.

But even before he could move in, the Nawab realised the palace’s proximity to a graveyard. Rather than hear the wailings of the bereaved come to bury their departed, he gave up the idea of residing in it. It was, however, all right for visitors to be troubled by the breast beating for His Highness re-designated his palace as a guest house and office.

For his own use he raised an even more fabulous retreat. Sadiq Garh Palace in the palm-saturated setting of Ahmedpur (aka Dera Nawab), 50 kilometres southwest of Bahawalpur, became the new pride of place. Nawab sahib was clearly taken by Italian architectural vocabulary. But this time, his appreciation of the Indian was wedded to the European.

Completed in 1895, in no fewer than thirteen years of painstaking intricate work, Sadiq Garh Palace became a very mixed extravagance of two styles. Here is a fantasy of Italian domes, bay windows with Mughal domelets, mock arches juxtaposed with pediments, and pillars with Doric capitals and the overflowing pot of Laxmi at the base. The Nawab’s fancy was duly matched by the skill of his architect.

This was a time when the Nawab maintained three capitals. Bahawalpur where he would entertain visiting dignitaries; Dera Nawab as an informal capital for private and state business and also his family’s residence. And across the dunes in the desert Derawar Fort, its clay ramparts now lined with fired bricks, the place for the traditional dustaar-bundi – the formal donning of the turban of kingship. As well as that, Derawar was the royal burial place. Even today, the stately domes of its many mausoleums, dusty and somewhat the worse for neglect, not far from the royal mosque recall a past grandeur.

Alas, Sadiq Mohammad IV could only enjoy the pleasures of this palace for four years. He died in 1899 leaving his building tradition and his fiefdom to his son Bahawal Khan Abbasi V. The young prince inherited the fine taste of his father honed by a first-rate education at Lahore’s Aitchison College and private tuition from a very able teacher. He not only followed his father’s building tradition, he redoubled its speed and accomplishment.

His reign saw a stupendous blossoming of new buildings. Darbar Mahal, foremost among the new additions, is a Mughal extravaganza. Sadly, this Nawab’s life was almost a replay of his father’s: Bahawal Khan too died early (in 1907) and left behind an infant son to be overseen by a Council of Regency. Even before Sadiq Mohammad Khan V wore the turban of chieftainship, he began to make his mark by continuing his father’s and grandsire’s superior building tradition.

However, where his forebears built palaces, this remarkable and civic-minded ruler with his eye on educational development in his kingdom raised the Bahawalpur Library in the 1930s and Sadiq Public School in the early 1950s. While the library created a reading public, the school, functioning to this day, has produced some very fine women and men to lead in various fields.

Ruled 1924 – 1966

Long before oil enriched the Saudi kingdom, Nawab Sadiq Mohammad V was shoring up the impoverished kingdom with lavish handouts. Later, though he ceded his kingdom to Pakistan with some hesitation, he was liberal with his financial assistance to the new struggling country. In his largesse, he gifted his private properties to King Edward Medical College and the Punjab University, besides a large tract of prime real estate to the Punjab government.

In 1955, Sadiq Mohammad ceded the independent State of Bahawalpur to Punjab province. Eleven years later this able and far-sighted ruler passed away leaving his erstwhile to a progeny that was nowhere near his visionary leadership.

The priceless built heritage of Bahawalpur fell into neglect. Invaluable pieces of fittings and decoration were pilfered by none other than the children of the late Nawab, the very inheritors of it all, who squabbled over possession of the various properties especially the exquisite Sadiq Garh Palace.

The abandoned palaces of Bahawalpur city may well have crumbled to dust had they not been taken over by the army in the late 1980s. Not all was lost!

Today Sadiq Garh Palace, the jewel of Bahawalpur’s crown, stands forlorn and wretched, its beautiful fittings plundered, its gardens unkempt and its rooms bereft of every adornment. It is a sad testament to the greatness of three of the finest rulers of a bygone dynasty that turned Bahawalpur from sand desert to a very orchard.