By Afia Salam

Environment activist Afia Salam visits Karachi’s first urban forest and talks to Shahzad Qureshi, the eco-entrepreneur who planted the seeds for this revolutionary conservation technique in Pakistan.

How many city slickers have experienced a forest? The quiet hum, the fragrant breeze wafting through the herbs and shrubs, the leaves of trees pungent with their fruits? The sudden drop in the temperature as you step into the shade of a tree, the buzz of the bugs and the chirping of different birds?

The way cities grow out, gobbling up green patches in the name of development, chances are that there may be an entire generation that has grown up without experiencing any of the above mentioned bounties.

But then it is not just the city dwellers. Even our rural areas have been stripped of the thicket of trees to make more and more land available for cultivation, and the disastrous agro-forestry policy is a whole different can of worms.

Here we want to talk about some other kind of worms, which are thriving in a patch of Karachi that was once designated as a park by the municipality, but had over time been turned into a garbage dump. These worms are now jostling for space with other bugs and insects that have found a happy new home in the mulch and natural environment of an ‘urban forest’ started by one concerned citizen, Shahzad Qureshi.

While the terms ‘urban’ and ‘forest’ lumped together may read like an oxymoron, it was an idea that was born out of necessity and a strong belief in the greater good. Qureshi is quick to credit the inglorious personification of the city’s growing problems, primarily in the context of climate change, as the ‘chief architects’ of this solution.

The lopsided development paradigm, where construction is leaving little space for breathing and much else, is a concern that requires immediate attention. The expansive built area and building materials are both contributing to alarmingly high temperatures.

Albeit Qureshi’s tech start-up makes him a citizen of quite another type of landscape (the virtual realm), it is his other business, a spa, that has kept him rooted firmly to solid ground, through his search for nature-based solutions. When Karachi was hit by the debilitating heat wave three years ago, some smart people started looking at the reasons, and possible solutions to avoid such an eventuality again. Although that calamity had a natural cause of air pressure and rise in temperature, there was consensus that the stripping of the green cover was the other contributing factor.

The shrinking area of existing parks, the disappearance of space allocated for new ones, and the development of ‘showcase’ parks with large grassy tracts sans trees, with bushes trimmed into shapes of bunny rabbits and dinosaurs, was hardly going to take the heat off Karachi-ites.

While Qureshi was convinced that fighting the vagaries of nature was certainly beyond him, he believed that at least a wrong done by some humans could be righted by others. During this quest, he happened to come across a video of conservationist and eco-entrepreneur Shubendu Sharma, who had grown a forest in his own backyard by adopting the award-winning Miyawaki method of restoration of natural vegetation on degraded land. They got in touch and he invited Sharma to Pakistan to help him replicate the technique.

Sharma obviously needed a space in which to start a forest, and Qureshi’s flurry of activity ensured that his neighbouring counterpart’s visit would not be in vain.

His start-up experience meant that he had the ability to go from concept to reality, and to do whatever was needed, in this case by making the municipality give him permission to ‘adopt’ the park-which-was-a-dump.

He then rallied around friends and well wishers, who not only dug into their pockets, but also vested their time and commitment into getting the park cleaned off, the garbage disposed properly, and making a space ready for Sharma to come and start the forest; all with friends, and their young ones in tow.

Since then, Sharma has visited Pakistan both in actuality and virtually, inspiring audiences and starting off patches in Lahore and Islamabad. But it is the ‘proof of concept’ in Karachi that is growing and thriving and gaining traction through word of mouth and amplification by the media.

More and more people, at individual, family and corporate level, are getting involved. People have been asking on different forums to be introduced to Qureshi so they can offer assistance. There are people who are offering him their unused pieces of land within the city, as well as on its outskirts so the initiative can be replicated.

Children who were part of the original plantation drive to set up the forest are now coming back to visit, demanding to see ‘their’ tree and more and more children are accompanying their parents to make donations for trees as well as planting them. One environmentally conscious mother also plans on suggesting tree-saplings to be a part of birthday goodie bags or gathering children to have birthday parties themed around actual tree plantation.

Already, a school near the park has its own very healthy patch of a ‘forest’ growing within its premises, also initiated by Qureshi, who now has big plans and dreams to maximize the benefit of the space he has adopted. He has had to allay the looming fear of the residents of this water-starved city that his forest would be taking their share of that precious, essential commodity.

For those unaware, it may help to know that his trees and plants are being fed by the brown water treated through reed bed plantation of ‘kaina’ a flowering plant that looks like a banana plant but has bright orange flowers. These have been planted over the sewage drain, and this method of bioremediation oxygenates the water, treats it and makes it useful for his plants, all 33 varieties of which are indigenous.

When you meet Qureshi, he is like an excited parent talking ceaselessly about his amazing offspring, and making plans for the future. He delights in seeing the ‘babies’ thriving and wishes to provide them a better enabling environment by seeking more and more resources for them to thrive in.

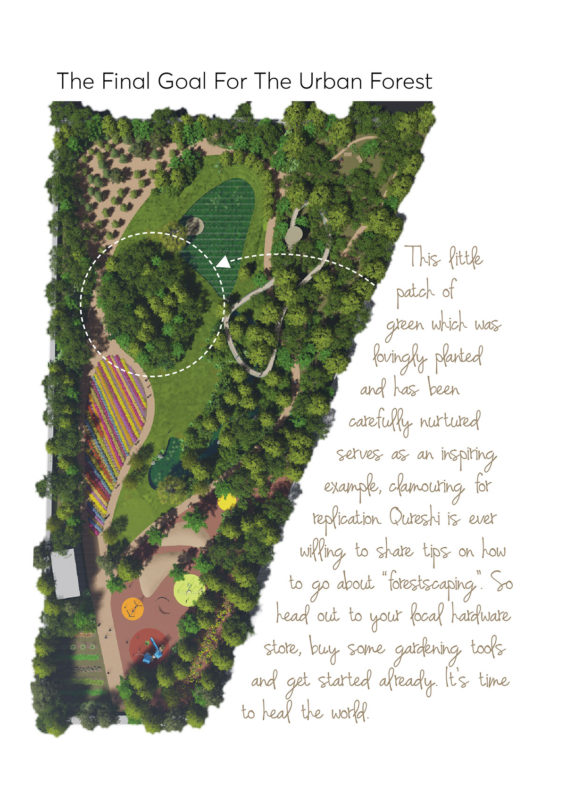

And he is planning big! The forest is in a circular match in the middle of the park. He is aiming for a butterfly park, an aviary, and a wetland, the beginnings of which can already be seen, in the area where the water is stored after piping it from the drain where it is treated biologically through the resplendent glory of flame-coloured ‘kaina’.

Of course, he has been advised by friends to eat this elephant bit by bit. There are unfortunately not many takers yet to take the entire project on, which is surprising because if one compares his estimates in terms of the education and recreational value of what he is trying to set up, the cost benefit analysis would definitely weigh them in the park’s favour. He has since been advised to make the offering modular, so he does not have to chase after one big sponsor but can allow many to have a buy-in, literally, into the process.

Qureshi has been busy promoting the urban forest, spending a considerable amount of time away from his core business to show it to whoever wants to see it. However, since it is not possible to clone either Qureshi or Sharma, we must find other concerned citizens whose imagination they can stoke to promote as many patches of green as there can be in the city, whether on a voluntary basis or through any other workable solution.

His ‘solution’ has raised eyebrows too. It has been argued that many of the local plants he has identified and recommended for future urban forests are available at various commercial nurseries at a fraction of the cost Shahzad quotes. Then why is he quoting sums that fall just short of four figures for the same plant, one may ask! It must be said that there is no wrong-doing. His math on this is quite simple. He says the amount he tags on each sapling is inclusive of the cost of the plant, and its watering, manure and nurturing by a qualified gardener for a 3-year period.

The other concern people have is that Shahzad Qureshi’s company “Urban Forest” is a commercial enterprise. So why should they ‘donate’ to an entity based on profit?

The successful start-up man Qureshi has a clear answer, “This adopted park is a Corporate Social Responsibility project of our commercial business. We invested all our money into it to get the pilot going, and now we are raising funds to scale it up.

The company offers consulting and turnkey project solutions to our clients who wish to create forests anywhere from their houses to factories and offices, schools, colleges, parks, open spaces, farm houses. Being a profit-based company pays for our time and manages to sustain our efforts in a line of business that benefits the environment and the people – whether directly or indirectly.

As for our adopted park, I strongly believe that we need to encourage, seed, fund, and subsidize eco businesses and make them so profitable that a vast majority of people would switch their professions and get into creating solutions for saving water, cleaning air, recycling all material, growing chemical-free food and green energy.

This is the only way to make rapid conversion possible from enabling earth-destroying habits to pursuing earth-restoring habits.”

For starters, let us get the word around. The more people talk about it, the more interested they are, and the sooner action would follow. There are no “quick fixes” here. And if you can’t come forward for tree plantation activities, then donate and watch the grass (or in this case, the tree) grow.

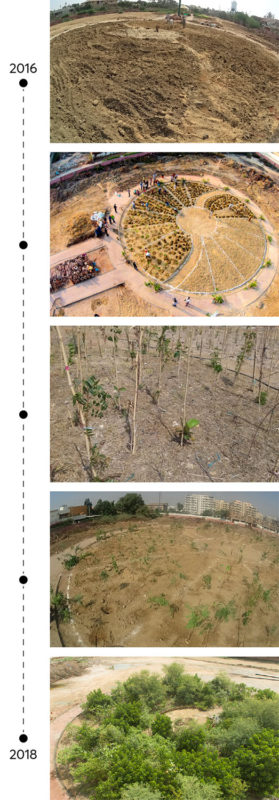

In a little over two years, some trees have already attained a height of over 10 feet, which is living proof of the fact that if nature is not interfered with, it has the capacity to heal itself.

This little patch of green which was lovingly planted and has been carefully nurtured serves as an inspiring example, clamouring for replication. Qureshi is ever willing to share tips on how to go about “forestscaping”. So head out to your local hardware store, buy some gardening tools and get started already. It’s time to heal the world.