Anarkali – the name has the ability to evoke a variety of emotions depending on one’s disposition. Shopaholics experience a rush of adrenaline at the thought of all the bargains on offer within the narrow alleyways of the thriving market. History buffs prefer to delve deep into the past and ponder over Anarkali’s Mughal and colonial heritage. And those who love a good tale remain forever enchanted by the myth that defines the origins of the bazaar.

The legend of Anarkali – the beautiful courtesan who seduced the Mughal Prince Saleem only to be entombed alive in a wall for her transgression by Salim’s father Emperor Akbar – has inspired poetry, music and films but no tribute is as enduring as the tomb built by the grieving Prince in her memory. Completed by Emperor Jehangir aka Prince Salim in 1615 to mark the spot where she was buried, the tomb gave name to the bazaar that sprung up around it during the time of the British, close to 200 years ago.

The history of Anarkali, that heaving, bustling maze of congested streets and tiny shops located outside the Lohari Gate, can be traced back to colonial times. According to noted travel writer Salman Rashid, the area originally served as barracks for the British Indian Army for a short while when troops moved into the Punjab following the clash of 1857. The cantonment soon shifted to Mian Mir, and the street became primarily residential. Eventually, business establishments began to flourish on the ground floors of the residential complexes, and over time, Anarkali became known as the poshest bazaar of its time.

“In the 50s and the 60s, Anarkali was the only market in Lahore,” recalls Rashid. “Back then, the city had a total of 200-300 automobiles and when ten cars gathered close to the bazaar, it created veritable chaos. Anarkali was home to locally made products; none of the Chinese stuff that has flooded the market these days. The one shop that stands out in my memory is the Kanpur Leather Store known for its stout leather suitcases the likes of which were not found elsewhere.”

Other old establishments included Inayatullah, known for its overcoats, dressing gowns and dress shirts, Bombay Cloth House, with its treasure trove of imported materials and saris of the finest French chiffon and softest English voile and Mohkham Din Bakery, renowned for its delectable confections. For a generation that saw Anarkali in all its glory, the sight is one that is hard to forget. Indian writer and scholar Pran Nevile, who was born in Lahore, reminisces fondly about the bazaar in his book Lahore: A Sentimental Journey. “With the passage of time, Anarkali grew richer and more captivating,” he writes. “By the late 1930s, it had become the most fashionable shopping center of the city and bevies of elegantly dressed women also began visiting it.”

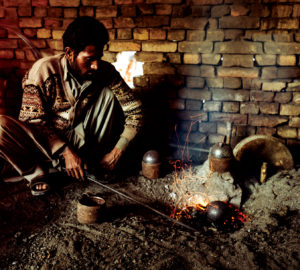

Describing the bazaar’s significance as a social and cultural hotspot, he writes, “Anarkali had also grown up as a place of recreation with a host of restaurants and bars, patronized by the landed gentry of Punjab and western UP who came to Lahore on a spending spree.” Today, the market may have lost its glamorous veneer but within its various iterations it still holds a significant appeal for those looking to sample a taste of the Lahore that used to be. Old Anarkali is known for its food street, where you can taste Punjabi street food at its best. Bano Bazaar is a kaleidoscope of colour offering a dizzying assortment of trinkets and accessories. Paan Gali brings a slice of Delhi to Lahore, with its wide offerings of Indian goods ranging from saris and jamavars, to herbal products, oils, bindis and rangolis.

Vibrant and chaotic, Anarkali embodies Lahore’s spirit of grandeur, contradictions and co-existence. Amongst shops selling everything from stationery to handembroidered khussas to fresh nimbo paani, you’ll spot architectural styles derived from the various eras to have shaped the city’s cultural ethos – from Mughal to Sikh to British. Sandwiched between buildings in the traditional sub-continental design adorned with wooden jhorakas lies the Anarkali Church, a red and yellow building that speaks of European influence. Sikh architecture is visible in the rounded cupolas of General Allard’s tomb near the historic Jain Mandir.

Not many visitors to Anarkali know that located inside one of the narrow alleyways exists the mausoleum of Qutub-din Aibak, the slave general of Mohammad Ghauri and the founder of the Slave Dynasty in South Asia. He was killed playing polo in Lahore and was buried at Anarkali. The tomb was originally constructed in 1210 and renovated by the government in the 1970s.

It is surprises such as this, and so many more, that add to the charm of the market – a beguiling mix of commerce, legend, history and that indefatigable spirit that makes Lahore such a culturally rich destination.