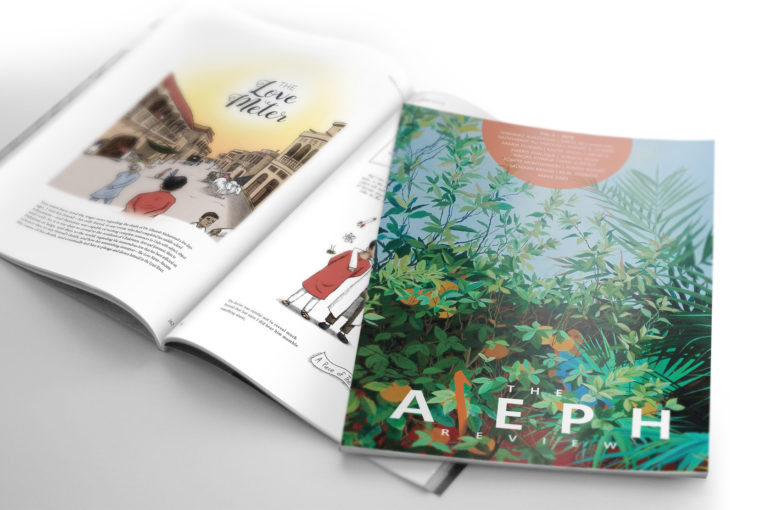

The Aleph Review is an anthology of creative expression covering all forms of poetry, prose and art. With its launch last year it provided a much-needed Pakistani platform where emerging talent can be published alongside the vanguards of literature and art. This month the Review came out with a vibrant second edition that includes contributors from the Pakistani diaspora abroad and other international talent. Insha Bukhari spoke to publishing editor Mehvash Amin about the Review and what it means for creative expression in Pakistan and abroad.

How do you pay adequate tribute to a mentor? For most, a name dropped in the course of a speech or a dedicated work does the trick. For indomitable literary powerhouse and poetess Mehvash Amin, though, simple just would not suffice. Setting out to honour her own mentor, the legendary Taufiq Rafat, Amin’s relentless pursuit of an appropriate ode culminated in the 2017 launch of The Aleph Review’s inaugural issue, a hefty anthology showcasing an immensely eloquent cast of Pakistani writers, blazing trails across a range of genres, sending ripples through the sub-continent’s intellectual and literary circles.

Now, with the release of The Aleph Review’s second volume, Publisher and Editor-in-Chief Amin is even more acutely aware of the weight of her wildly ambitious work. Plainly acknowledging that a sizable chunk of commercially acclaimed South Asian literature is heavily dominated by a buffet of stereotypical tropes – war, violence, toxic patriarchy, stifling cultural traditions, the plight of the poor, the excess of the elite – Amin bravely and purposely chooses to deviate, curating a powerful collection of literary contributions that need no crutches.

Skim the journal and it is obvious that amongst Aleph’s motley mix of authors, being South Asian is secondary, almost an afterthought. More prominently, this is a group of distinct voices, masterfully removing just enough of the self and its overburdened sensibilities to focus on their subject and shine across a multitude of genres. Equally exciting, the linguistic prowess of an incredibly accomplished literary guard – Athar Tahir, Ahmed Rashid, Sorayya Khan – flawlessly mingling with an invigorated flank of fresh, rising aspirants the likes of Palvashay Sethi and Mina Malik Hussain, bringing together a cadre who are, above all, committed to their craft.

DESTINATIONS spoke to Mehvash Amin for a preview of what readers can expect from this issue, her thoughts on the current literary landscape for both aspiring and accomplished writers in the sub-continent, and where The Aleph Review is headed in the future.

The Aleph Review’s inaugural issue cantered on your mentor Taufiq Rafat’s seminal essay, “Defining the Pakistani Idiom,” in which he writes of an exquisitely talented, burgeoning literary class experimenting, moulding, and reshaping the English language to suit and reflect their native sensibilities. Are you optimistic about a similar revival within Pakistan’s modern literary landscape and how would you define the modern Pakistani idiom?

What Rafat was talking about was mainly a group of poets, writing poetry that delighted in the ownership of a ‘Pakistaniat’ that encompassed both language and perception (there were other poets like Adrian Husain who did not agree with Rafat et al).

With the rise of the Pakistani novel, firstly poetry has been relegated to a second place and the celebratory ‘Pakistaniat’ of before has turned into the lucrative one of bombs, mullahs, sectarianism, etc. Not an idiom as much as a dubious gift from the Western publisher – write about these things and we shall publish. I do not agree with that, I think we should go on from both the Pakistani idiom and the Pakistani trope to write about whatever we want to. I hope we can mature into writing without thinking of the Pakistani idiom. That was necessary then, now we need to think in terms of great writers who happen to be Pakistani writing great literature.

Literary anthologies are often considered ominous volumes by writers, for writers. What makes The Aleph Review approachable and relatable for the average reader?

I think it is beautifully laid out, with blurbs that should draw the reader into the text and accompanying art that is reflective of the writing alongside which it is placed. Beyond that, perhaps you have to love reading to like it. Words have to be a part of your DNA. It is certainly not airport reading, but then there is a lot of that around.

Commercially successful South Asian authors tend to veer towards subject matter that reinforces a too-broadly painted portrait of the modern South Asian experience. Is the ubiquity of these themes stifling aspiring authors into a specific style of writing?

With some writers, sadly, I feel that is very true.

“Tired” by Eissa Saeed, “Not Man Enough” by Muneeb Ahmed Khan and Sehba Sarwar’s expertly woven “They Will Make Muslims Out of Us” poignantly point out the simmering frustration of a South Asian community that feels detached from an identity forced upon them by circumstance. Could this sense of alienation become a catalyst for South Asian authors to explore a more diverse range subject matter?

The sense of The Other is a universal theme. As for the issue of alienation, I think it holds true for Muslim writers as opposed to merely Pakistani ones. That sense of victimization and the ensuing rage will definitely be a subject as long as the present political climate lasts.

The genres and categories featured in the Review change annually. Is this fluidity designed to encourage authors and aspirants to move beyond their comfort zones and explore new ground?

Definitely. When I visualised the Review, I wanted to include all kinds of creative writing. Last time we had a section titled Epistle/Reportage. Another called Screenplays. This time we have a graphic story, Magic Realism, so many others. We found a unique voice that could only go under the title of Alternative Writing. Sometimes serendipity plays a part in creating a section. This time we received four essays that came under Food, Skin, Body and Music and I couldn’t help titling them Epicurean Essays, though the approach of each writer was not epicurean as such.

With a section dedicated to Magic Realism and sci-fi masterpieces such as Annie Zaidi’s “Wandering Womb” that delve into imaginary worlds, even touching upon the supernatural, there remains a uniquely human element to each of these stories – longing, acceptance, loss, loneliness. Was this a serendipitous happenstance or were contributions selected because they included these elements?

You know, if the writing is good, these universal, human elements will always be a part of it, no matter what ‘category’ it fits in. So basically, we are looking for good writing.

What was the purpose of a Translation category in this volume?

There is so much good work in Urdu that would be lost not only to people abroad, but even to our English-thinking elite if it were not translated. I believe passionately in translation.

Shahnaz Aijazuddin, who translated the formidable, “Tilism e Hoshruba,” spoke of the importance of “retaining the flavour of a language.” Could you explain what Mrs. Aijazuddin meant?

I will tell you a little story of my own to illustrate what she meant. While doing French Literature, I read Camus’ The Outsider (L’Etranger) in French. But for our BA degree we had to read it in English as well. I chafed every time I had to read it, because where Camus intended his protagonist Meursault to be removed and almost philosophically detached, in that translation he came across as an individual who was just coarse and hedonistic.

I was delighted when a second translation of the book came along, closer to the original. I remember even Time magazine reviewed the new translation, and said exactly what I had felt about the first one.

Good translation is that important. You do not just translate words, but a whole way of thinking – not just the author’s, but also the ethos from which the author comes.

The Aleph Review prides itself as platform for young, aspiring writers and poets. What is your advice for authors interested in contributing and what kind of guidance does Aleph offer during the editorial process?

Ah, such a good question. We had two new voices this time that we thought were promising, but needed editorial input. One accepted the heavy editing – not changes, but pruning – that I inflicted on his work and is in the book. The other did not, I think because of his ego, and Ilona and I decided not to include his work because some bits were brilliant and some just didn’t make sense. I remember when I started writing poetry, I accepted every change suggested by Kaleem Omar, my other mentor, because I trusted his editing. I think younger people should realise that no good editor would suggest changes unless they improve their work.

Could you tell us about the value of mentors?

When I started writing poetry, the fact that Taufiq Rafat and Kaleem Omar mentored me made all the difference to me – they actively showed me how a poem is written, that sometimes you have to rework it perhaps forty times to get that perfect balance. They ground my ego into the dirt. You may be talented, they seemed to say, but you will have to work like a dog to give a proper voice to that talent. If it hadn’t been for them, I might not have stuck to writing through marriage and kids, I might not have come to the stage where I said: okay, I am going to start a journal which will encourage new talent to come forward. If I encourage even one young person to continue writing and become a good writer – as opposed to a merely successful one – I think the journal will have acted as a mentor.

Ultimately, as a collection, the second volume of The Aleph Review decisively reinforces the anthology’s founding mission, to showcase the best of South Asian writing, while staying true to its guiding philosophy that a singular, homogenous South Asian experience and identity neither exists, nor is it necessary to create an impactful, lasting piece of literature.