The Soan Valley is an area measuring 780 square kilometer, located in the northwestern part of district Khushab in Punjab. Sher Shah Suri coined the name of the area due to the sweetness of its water (Khush-ab). The valley and its surroundings boast some extensively rich history. Soan is now considered home to what might be the earliest civilization in human history, as evidenced by the recent discoveries of ancient stone tools here. It goes with the nature of this place that such a significant finding would go almost unnoticed.

Gripped by a desire to explore this beautiful area and discover the ruins of Hindu temples and Buddhist stupas that I knew existed here, I left Lahore with my friends Ali and Hasan for a three-day trip. We had booked a room at the Sakesar PAF Base, the highest and the farthest point of the valley, and planned to use it as a base for excursions into the valley.

There are many ways to get to Soan Valley and most take around 6 hours from Lahore to Sakesar. Our first stop was meant to be the Kanhati Gardens, built by the British in the 1930s. I had heard of a waterfall there and we proceeded to it in the hopes of beating the heat with some fresh, cold water.

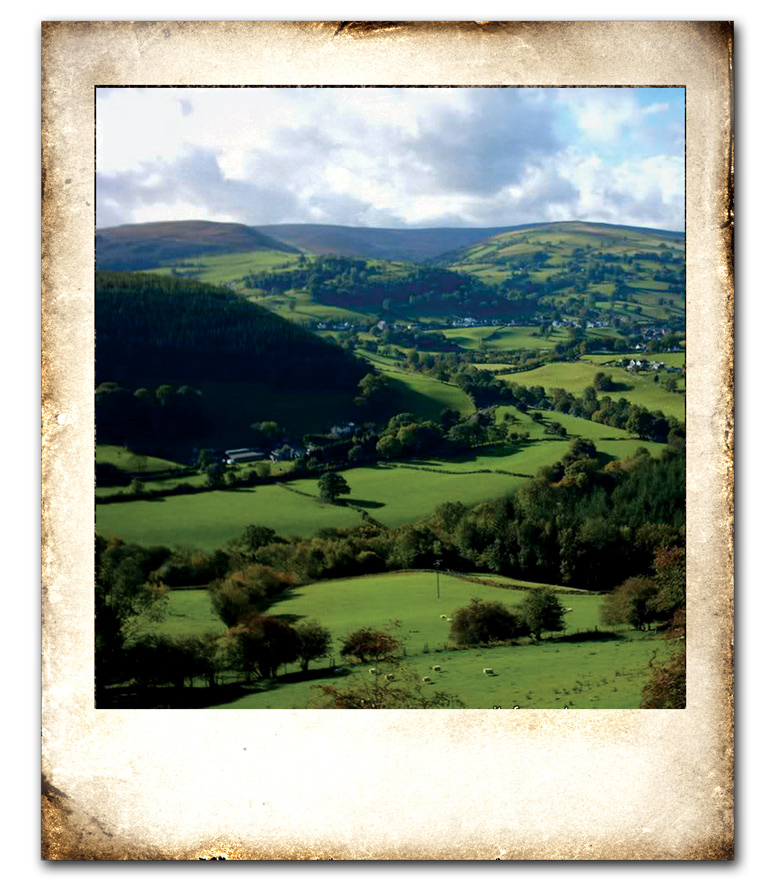

To describe the terrain of the valley is next to impossible since there is seemingly no set characteristic to it. It resembles the American Wild West in some places, the Australian Outback in others and there are even hints of the rolling green meadows of the English countryside in several places.

One moment we were driving though a forest, only to find ourselves on a vast plateau next, flanked by a barren hill on one side and the vast, unending plains of Punjab on the other. It was beautiful and bewildering at the sametime and ensured that the journey never became monotonous.

Chambal Mandir

Around 30km before Kanhati Gardens we spotted a board indicating the direction for Chambal Mandir. There was no mention of such a temple on Google Maps or on the web. But since there was a sign, we decided there simply had to be an actual temple as well. Asking for directions from the first people we encountered, we set off down the canyon.

Around 30km before Kanhati Gardens we spotted a board indicating the direction for Chambal Mandir. There was no mention of such a temple on Google Maps or on the web. But since there was a sign, we decided there simply had to be an actual temple as well. Asking for directions from the first people we encountered, we set off down the canyon.

It seemed like a strange place for a temple. The path downwards was quite steep and we had to climb over rocks all the way to the bottom. The only sound we could hear was the loud and melodious chirping of birds. Around 15 minutes later, we suddenly came upon a leafy part of the mountain and the songs of the birds amplified. Scores of colourful butterflies whirled around us in a frenzy, like something out of a fairytale. There was a rusted iron gate in front of us and what looked like fortified walls around it. We were disappointed because it looked nothing like the temple we had imagined. The trees were beautiful though, and to get a better view I climbed atop the wall. To my delight, inside the walls was an actual temple!

A serene pool of water lay in the middle of the structure, surrounded by more greenery than I had ever laid my eyes on. The trees were massive, especially the Buddha trees, and their size and girth left little doubt that this place was centuries old. The temple grounds were built as terraces on the edge of the cliff and at the bottom, was a small stream of water whose sound echoed throughout due to the narrowness of the canyon. Birds of several colours could be seen flying around. It was a nature lover’s paradise. The arduous hike back to the top of the canyon explained the low profile of the temple but we were not complaining. Chambal Mandir was the cleanest and greenest part of our whole trip, free from the litter that defaces natural beauty.

A few minutes away from the temple was the shrine of a pir and we gave it a cursory look. Preparations were underway for an urs after sundown and men, women and children could be seen gearing up for a celebration. We saw numerous shrines during the trip, which indicated the large presence of Sufi leaders in centuries past – yet another reaffirmation of the area’s historical significance.

Kanhati Gardens

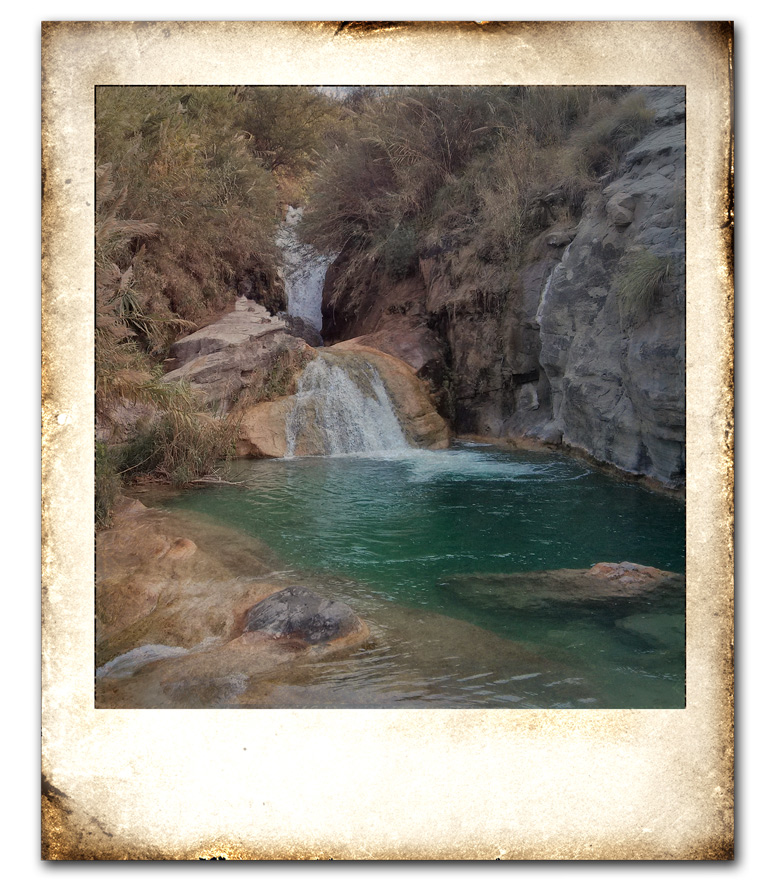

The gardens are located about 9km into a side road from the main Naushera-Jaba road, a route that presented stunning vistas. After a series of tough but rewarding side expeditions, what awaited us was the perfect culmination to a hot and heavy day. The gardens were beautiful, as most British-era gardens usually are. The highlight, though, was the waterfall and the view that preceded it.

The gardens are located about 9km into a side road from the main Naushera-Jaba road, a route that presented stunning vistas. After a series of tough but rewarding side expeditions, what awaited us was the perfect culmination to a hot and heavy day. The gardens were beautiful, as most British-era gardens usually are. The highlight, though, was the waterfall and the view that preceded it.

An endless sea of strange red rocks met the eye wherever it searched, interspersed with some green shrubbery and what looked like the white remains of what once used to be a river. The brain was unable to make sense of it all. It did not need to. Just gazing at this strangely mesmeric view was enough. Yet this was not even the best view of the next hour.

The waterfall was a let-down at first. The pool at the bottom was used as a garbage dump and hence was completely unappealing. alloescort.ch. However, I climbed up to the top and was stunned by what lay before me. After the long hike under the blazing sun, God had prepared for me the perfect denouement to the day – a Jacuzzi by the sunset full of clear, clean water. It even had a natural jet of water that kept a constant stream in and out of the Jacuzzi. I had uncomfortably lugged a watermelon during the walk and it was the perfect food to eat in such a setting.

Ambh Sharif

The next morning we had an early breakfast at the Sakesar PAF base, with a view of the adjacent Namal Valley and headed to Ambh Sharif, the location of the famous Hindu temple on Sakesar Mountain. It was about an hour’s drive from the base on the road to Quaidabad. The drive this time was not through a plateau or valley but around crimson mountains laced with purple and yellow rocks.

The next morning we had an early breakfast at the Sakesar PAF base, with a view of the adjacent Namal Valley and headed to Ambh Sharif, the location of the famous Hindu temple on Sakesar Mountain. It was about an hour’s drive from the base on the road to Quaidabad. The drive this time was not through a plateau or valley but around crimson mountains laced with purple and yellow rocks.

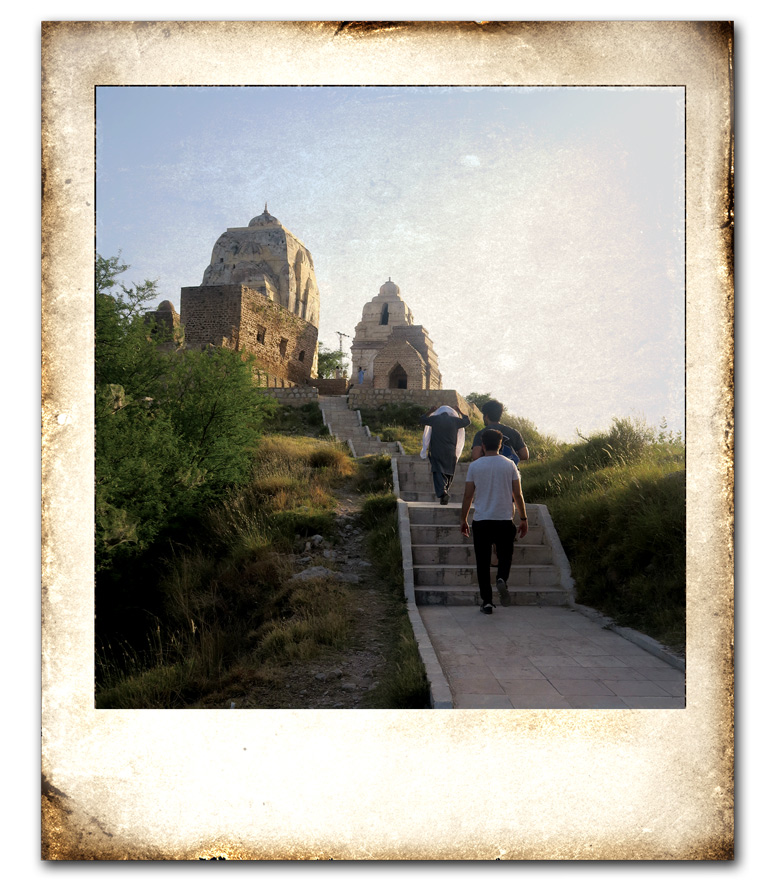

Ambh Sharif actually derives its name from a shrine located about five minutes away from the better-known Hindu temples – a great example of religious harmony and coexistence. The temples are architectural marvels and are believed to be more than a thousand years old, dating back to the Hindu Shahi period from 615-960 CE. The smaller structure is set on the edge of the cliff while the bigger, multi-storied building is about 50 yards further. The setting gives the temples an extra touch of divinity, as if perched on the pinnacle of a mountain amongst the clouds of Eden.

The sheer size and complexity of the temples was an eye opener. The brick and mortar structures made the carvings and designs seem even more intricate and extensive. Unfortunately, the walls had been stripped of the statues that had once adorned them. Gaping holes in the exterior also pointed to the presence of precious gems in the past and the locals confirmed this.

Steep stairs leading up an adjacent mountain uncovered more ruins. Upon inquiry, the locals told us that this was probably the mansion of an ancient king who ruled the area and the temples were built for his private use. This may not be historically accurate as the supposed mansion’s completely ruined state suggested that it predated the temples. The mystery, however, can only be solved by digging for further remains. The fact that such magnificent temples in such a stunning location can be ignored, is astonishing. A rich history, an ethereal setting and complex masonry make it the perfect candidate to be labelled a UNESCO World Heritage site; yet, most Pakistanis don’t even know of its existence.

Sakesar

The Sakesar base was built in the 1950s and is beautifully designed in conjunction with the topography of the area. It was an oasis of calm, despite the presence of a large number of guests. This was due to the extremely high number of trees which not only housed birds that chirped merrily all day but also covered the terraces in such a way that you felt isolated in your own little world. Wild olive, apricot and pomegranate trees provided a lush green cover all around us.

The Sakesar base was built in the 1950s and is beautifully designed in conjunction with the topography of the area. It was an oasis of calm, despite the presence of a large number of guests. This was due to the extremely high number of trees which not only housed birds that chirped merrily all day but also covered the terraces in such a way that you felt isolated in your own little world. Wild olive, apricot and pomegranate trees provided a lush green cover all around us.

Sunset at the saltwater lake Uchali, right beneath Sakesar, was a surreal experience. A narrow road has been built into the middle of the lake where a strong and pleasant breeze blows constantly. The sun disappeared behind the Sakesar Mountain just as it does in those seemingly quixotic children’s paintings.

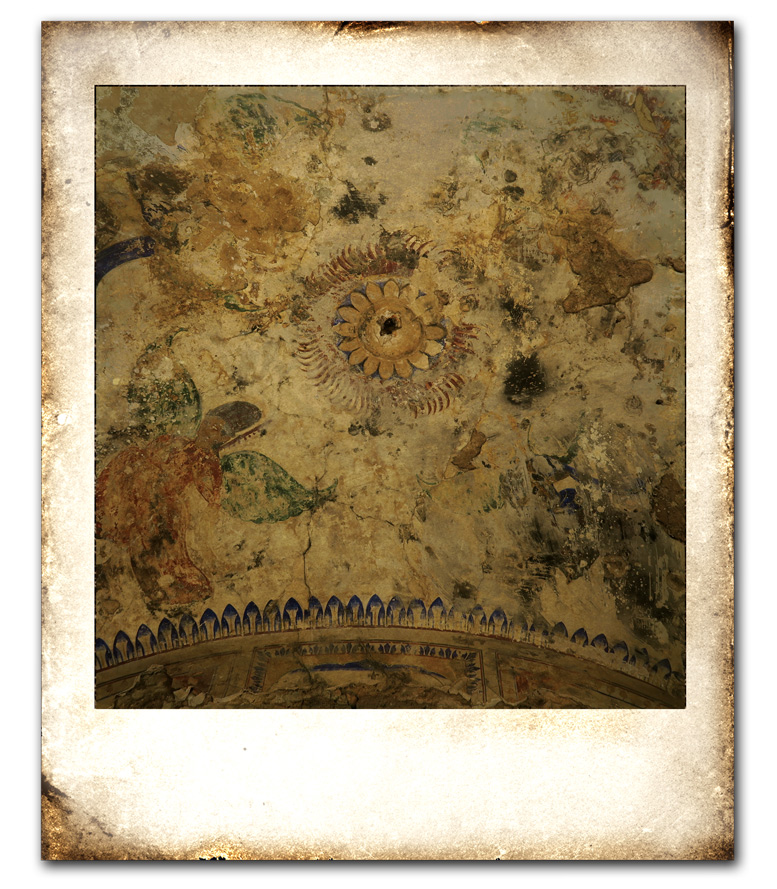

We also found the remains of a gurduwara at the base. It had also been stripped of its jewels but some parts of the deliciously colourful wall paintings remained.

The dominant sound throughout the trip had been the soothing clank of cowbells. In some inexplicable way it provided a sense of calm, as if reassuring the traveller that this was a safe, domesticated place.

Being a city dweller brings with it a mistrust of strangers, but the people we met on the trip forced us to shed our misconceptions. Our queries and questions were never met with disdain, but with an enthusiastic and earnest response. The people exuded a relaxed and happy vibe; however, to assume this was so due to the lack of pressure the village people face is to know nothing of the perils of the small farmer.

The weather, topography and people of the region are considerably different from those of Central Punjab. The main language is Saraiki, spoken in a sing-song lilt. What is even more striking is the fact that we did not once encounter anyone playing cricket! Instead, volleyball was the sport of choice and it is said that Pakistan’s best players come from this region.

The Soan Valley and its adjacent areas are indeed a land within a land. From the Paleolithic Stone Age to the Gandhara period and the subsequent Hindu Shahi and Muslim eras, the valley has remnants of all and is a must-visit for lovers of history and culture. The Punjab government has promised to pump money into the area and make it a tourist spot and if the past is anything to go by, now is the time to visit before the inevitable desecration takes place.