The sun has just dipped beneath the dunes, setting the western horizon ablaze. Overhead, a coppertoned waxing moon hangs against the first stars of night. The sand, already beginning to cool, tempers the desert air soughing through the branches of the kundi tree where four or five owlets engage in a nattering argument. The day done for him, Allah Vasaya leans back against the bolster on his charpoy under the kundi.

From the direction of the toba – the pond that slakes man and beast alike – he hears the clangour of livestock bells and he recognises the deep, resonant bhoongan sound of the one his prized bull wears. The animals are drinking for the night and soon the bull will lead the rest of Allah Vasaya’s livestock home. Minutes later, the ringing becomes a medley of sounds from the bells of his cows and the smaller ones worn by sheep and goats.

The ability to recognise the sound of the bell – tull as it is called in Seraiki and Punjabi – on his lead animal is not a gift endowed upon Allah Vasaya alone. It is something every livestock owner in Cholistan can do with ease. Indeed, from the desert in the east to the canal-irrigated region of Bahawalnagar and the districts in the south, livestock owners have the same ear for animal bells. And everyone knows the best bells come from the little village of Sheikh Wahin near Chishtian in Bahawalnagar district.

The elderly Faiz Baksh of Sheikh Wahin says his family has been in metallurgy for ten generations and more, that is, a little over two hundred and fifty years. Time was when the family’s major production was swords and shields. In the early 19th century the family was also gun smithing and had become quite adept at the craft. Post-1947, says Baksh, this latter was completely given up.

It was the family’s mastery in producing bells that won it renown, however. This is a craft they have practiced for more than a century. Says Faiz Baksh that he can produce two of the large bhoongan bells of exactly the same weight, yet the tenor of each will differ. He says that even if neighbouring livestock owners used those on their animals, both would be able to differentiate the ring of the tull.

Baksh says bells come in three sizes. The large one for camels or lead cattle; medium for herd members and the smallest for goats and sheep. While the medium and small ones may not necessarily produce differing tones, it is essential, says Baksh, that the sound of each large bell be discrete from every other, even if in a barely noticeable degree. According to the man, this fine difference is created by the coating of brass that goes on the finished raw item.

Baksh says bells come in three sizes. The large one for camels or lead cattle; medium for herd members and the smallest for goats and sheep. While the medium and small ones may not necessarily produce differing tones, it is essential, says Baksh, that the sound of each large bell be discrete from every other, even if in a barely noticeable degree. According to the man, this fine difference is created by the coating of brass that goes on the finished raw item.

In a street in the heart of Sheikh Wahin, three young men recline against a wall hammering away at pieces of iron set against steel lasts to give them the bell shape. Bells of all sizes are crafted in two different parts: the cylindrical lower end is one, while the cap-shaped top with the suspending loop fits on the lower. Both parts are not riveted, rather hammered together. To create a stronger bond for the greater weight of the large bell, the jointing is done over fire.

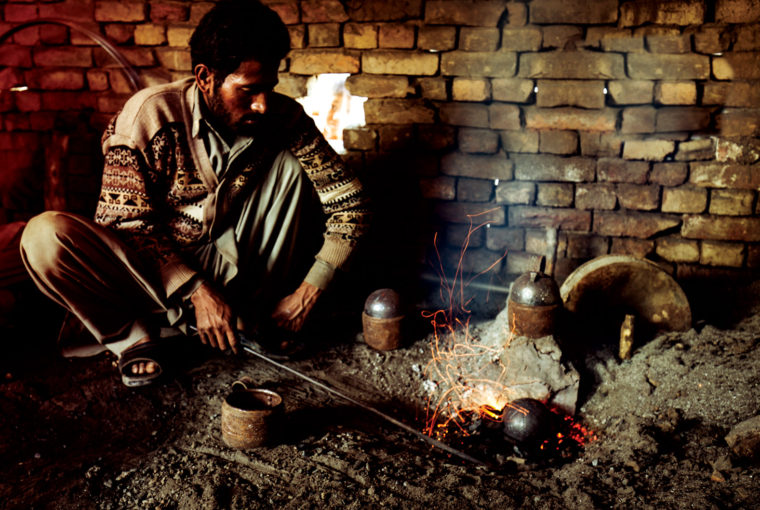

The bell, with bits of brass around its body, is liberally slathered with a coat of clay and arranged on a bed of coals in a shallow, circular baking oven. The furnace is so primitive that it may not have changed since they first began using it during the Harappan heyday. Several dozen clay-coated bells are arranged in the oven and covered over with coals. Since nothing is done manually nowadays, a motorcycle with its rear wheel raised above ground is rigged to a blower turbine to fan the furnace.

The bell, with bits of brass around its body, is liberally slathered with a coat of clay and arranged on a bed of coals in a shallow, circular baking oven. The furnace is so primitive that it may not have changed since they first began using it during the Harappan heyday. Several dozen clay-coated bells are arranged in the oven and covered over with coals. Since nothing is done manually nowadays, a motorcycle with its rear wheel raised above ground is rigged to a blower turbine to fan the furnace.

Within minutes of fanning the coals glow an evil yellow-orange and I estimate the temperature rises to well over 800 degrees Celsius. After about forty minutes of baking, the top layer of coals is hauled off to reveal that the clay on the bells has turned into blackened slag. With hoe-like implements, the men set to separating the slag covered bells and wait for them to cool. The outer slag is smashed and out come burnished little bells.

Faiz Baksh says that the brass plating of the large bells is more difficult as each piece has to be brass-plated separately. He also tells me that after a few years of use, the large bells lose their tenor. They are then returned to his workshop to be reconditioned. Once again the bell receives the brass plating treatment and is again as good as new.

Following the plating process, the ready bells are fitted with the clapper – the lara (palatal r). In Punjabi and Seraiki, this is the cognate for bridegroom and as a wedding is never replete without this all important protagonist, so too the bell without its lara, explains Faiz Baksh. The smaller models come with metallic laras; the ones used on cattle and camels have wooden ones.

We are told that the bhoongan model can cost up to Rs 10,000. And that time was when bells supplied at calving time were recompensed with a cow. But today things are so bad, Faiz Baksh says wistfully, he has to buy his supply of wheat flour on a daily basis. He is somewhat circumspect about the reason of the industry’s privation until one of the hangers-on lets out that the middleman who supplies the ready ware to the market skims off the major profit.

This man, whose name I never asked, sitting serenely on the charpoy next to me and never divulging his role smiles sheepishly. Why, the bell-makers are so poor they cannot procure raw materials in bulk and he provides them everything on credit. If he refused to play ball, they would go out of business, he says. It is therefore his right to take the ready products. But not at the cut-throat price he offers the craftsmen, says the interlocutor who had just given away our villain. The man lamely tries to justify his loan-shark role but no one buys it. He looks at me and grins. The grin refuses to fade. Faiz Baksh says he and his relatives are the last bell makers in lower Punjab and their famous wares every evening herald the returning livestock from Bahawalnagar to villages in Rahim Yar Khan and Dera Ghazi Khan, three hundred kilometres away. But they barely make a living, existing on the goodwill of the grinning loan shark who will forever hold them in monetary thrall.

This man, whose name I never asked, sitting serenely on the charpoy next to me and never divulging his role smiles sheepishly. Why, the bell-makers are so poor they cannot procure raw materials in bulk and he provides them everything on credit. If he refused to play ball, they would go out of business, he says. It is therefore his right to take the ready products. But not at the cut-throat price he offers the craftsmen, says the interlocutor who had just given away our villain. The man lamely tries to justify his loan-shark role but no one buys it. He looks at me and grins. The grin refuses to fade. Faiz Baksh says he and his relatives are the last bell makers in lower Punjab and their famous wares every evening herald the returning livestock from Bahawalnagar to villages in Rahim Yar Khan and Dera Ghazi Khan, three hundred kilometres away. But they barely make a living, existing on the goodwill of the grinning loan shark who will forever hold them in monetary thrall.

But Faiz Baksh and his clan know that the people of Cholistan will forever remain livestock and camel herders. And forever and the day, they will need the bells to tell them if it is their animal or the neighbour’s they hear headed back to the village. The craft will never die. Even if they have to buy food on a daily basis, the elderly craftsman knows that his clan will forever continue to make their bells.