A visionary, an original, one of the greatest abstract artists of our time – Waqas Khan has been described as all this and a lot more. His intricate drawings are coveted by top international galleries and collectors, and featured amongst the permanent collections of the world’s most prestigious museums. In this exclusive two-part series with DESTINATIONS, the artist shows us around his home and studio in Lahore and takes us on a retrospective journey that begins in rural Punjab and sees him take on the world. In the second segment, photographer par excellence Abdullah Haris shoots Waqas Khan at one of his favourite Lahore spots, the historic Lahore Fort, once the seat of royalty and power and a befitting venue for the reigning star of the global contemporary art scene.

On what he would have preferred to be a leisurely Sunday evening spent at home, Waqas Khan is stuck in a snarl of traffic just outside Old Lahore, at the entrance of the shrine of the Sufi saint Data Ganj Buksh. The urs (death anniversary) of the ancient mystic is just a few days away and devotees have begun arriving by the hundreds for the 3-day celebration that will mark the occasion.

“No wonder I don’t get out of the house any more,” he smiles, good-natured and unfazed despite the delay the jam has caused him. Is it the traffic that’s keeping him away, I joke, or the fact that as the hottest new star of the international art world, he spends more time catching flights to art fairs, exhibitions and biennales across the globe than he does navigating the streets of his current home city? “It’s probably the latter,” he laughs.

Coming from any other person, such an admission might come across as arrogant or self-congratulatory. In the case of Waqas, it’s a simple, guileless acknowledgment of his current status, which has seen the Guardian compare him to the likes of Rothko and Mondrian, two of the greatest abstract artists of the 20th century.

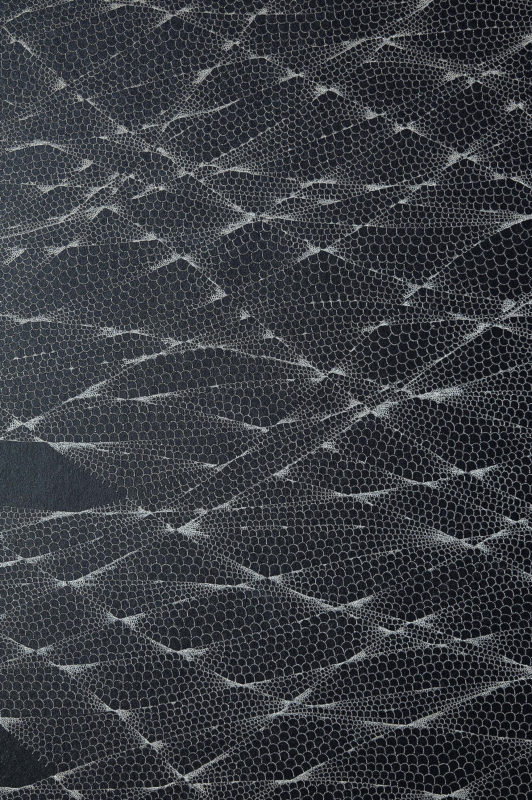

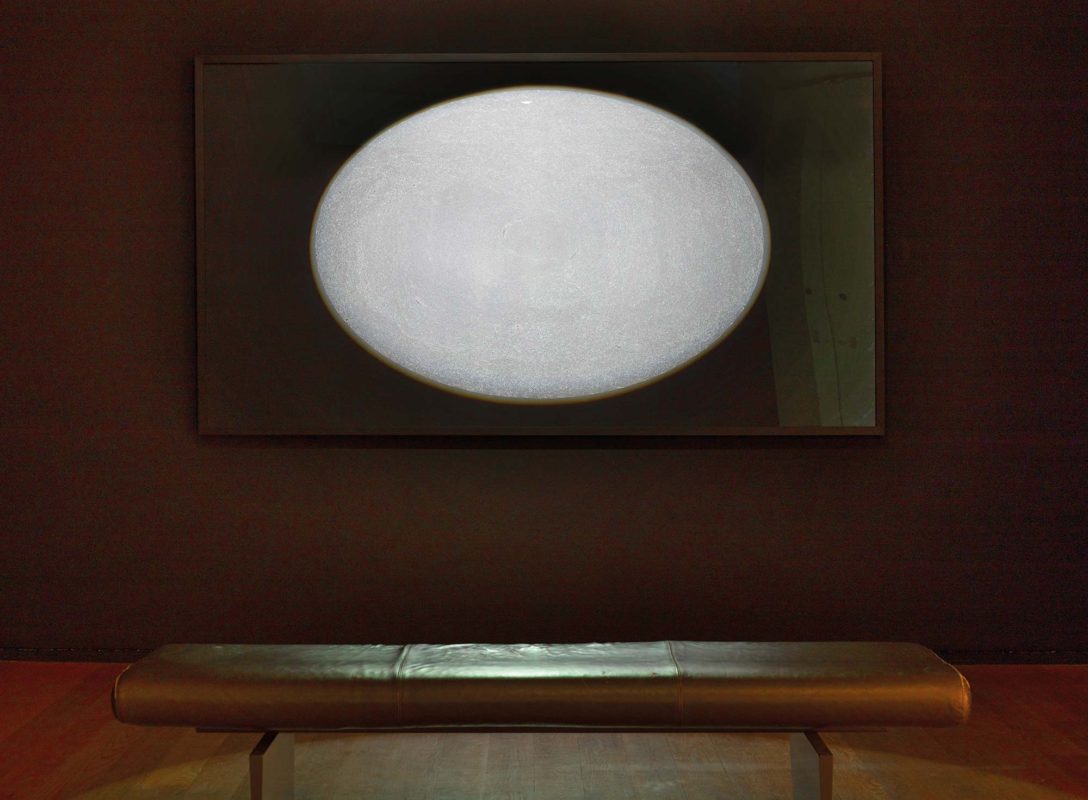

Waqas makes intricate, detailed drawings, comprised of precise tiny dots and dashes arranged in lines and circles that expand to form soothing, meditative expanses resembling delicate webs and celestial shapes. His works are part of the public collections of prestigious organization such as The British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (UK); the Deutsche Bank Collection, Frankfurt (Germany); the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art and The Devi Foundation, New Delhi (India). His art has been described as “delirious and disorienting,” and “blazing with spiritual intensity” by critics around the world.

Such rapturous reviews are, of course, humbling, admits the artist. “But what really inspires me is the people around me and how they interact with my work. I want to make connections with everyone,” he says. “I want to know what he thinks of my work,” he gestures towards a devotee in a brightly coloured shawl crossing the road in front of our car. “Someone like him will ask me, ‘how the hell do you find the time to do all this?’ and I love that purity, that honesty.”

The jumble of people and vehicles finally untangles, and as we cross the shrine, which will be lit up with thousands of candles and lights and resounding with the hypnotic sounds of drums in just a few days, I bring up Waqas’ own connection with Sufism that has been referenced extensively by the international press.

“I tend to get boxed in with Sufism, but I have always been very clear that I don’t talk about Sufism, I only talk about the Sufi poetry that I grew up hearing my elders recite. In small communities such as my village, people interact, they sit and talk and share stories.” The tales that a young Waqas heard encompassed universal themes such as love, truth and devotion, and it is this universality that is now reflected in his art.

It is art that, in its refusal to be pigeonholed into themes and subjects one might expect a Pakistani artist to conform to, often tends to take the viewer by surprise. “The first question a critic ever asked me during my early international shows was, ‘are you really from Pakistan? Where are the guns, the blood, the woman in a veil?’”

Nothing gives Waqas greater pleasure than such instances of confounding expectations. Another story he enjoys recounting is of his first European show back in 2012. With him not present at the opening, many of the guests believed they were viewing the works of a female artist. “Can you believe, they thought I was a woman?” he laughs. It’s a mistake one can easily be forgiven for, I admit, given the striking contrast between the delicacy and gracefulness of the work and the strapping, burly 6’2’’ physique of the artist creating it.

Waqas’ journey to becoming one of the most celebrated new artists of our times has been similarly unpredictable. It began in a small village called Akhtarabad, near Okara in rural Punjab, where his family owns agricultural farms. With two younger brothers who moved away to pursue careers, Waqas stayed behind to look after his parents and tend to the family lands. He was eventually sent to Lahore to study in an all-boys government college, and ended by at the nearby National College of Arts (NCA) after his aptitude for drawing was spotted by friends and teachers.

“NCA was a culture shock for me, a complete departure from the environment that I was used to,” he recalls. “The thought of being an artist had never even crossed my mind up until then. It took me three tries to get in. By then, I was already part of the NCA family because I had been living in the hostel for 3 years and knew everyone.”

Photographer: Michael Pollard

Courtesy of Manchester Art Gallery, the artist and Sabrina Amrani Gallery

Contrary to what his stellar professional accolades may suggest, Waqas was hardly a model student, rarely attending classes and barely scraping through semesters. It wasn’t until his 4th and final year, when he started working on his thesis collection titled ‘Dot’, that a sense of purpose began to permeate his creative process. “I started working on the idea of making a connection. I wanted to know how to make people see spaces and interactions in a different way.”

This reimaging of the concept of space has remained one of Waqas’ primary motivations and is reflected in his recent work, the ‘Khushamdeed’ signs placed across Manchester, a city that also happens to be the venue of his ongoing exhibition for the New North South programme. ‘Khushamdeed’ is an Urdu word meaning ‘welcome’ and Waqas’ neon installations at three of Manchester’s museums and art galleries are an intriguing invitation to the city’s diverse population to step inside.

The idea came to him when he noticed that Manchester’s vast South Asian and Arabic communities seemed hesitant to enter many of its buildings. “They didn’t connect with the structures, I could tell,” explains the artist. The bright Urdu lettering is now making those very people stop for a second look and increasingly, cross the threshold. “The installation has literally activated the community, people are now stepping inside the buildings. The whole point of the works is to start a dialogue, get people to let go of preconceived ideas.”

Like the neon signs that offer up a friendly yet compelling invitation to all, Waqas draws in people with his openness and eagerness to start a conversation. From the technicians at the Manchester Museum who helped set up his installation, to the international art critics covering his shows to the domestic staff that works at his home in Lahore, he knows them all and treasures their opinions.

In fact, when the Sabrina Amrani Art Gallery in Spain that represents him asked for names of Pakistani critics who could analyze his work for one of its publications, he insisted on having his mother and his cook send in their opinions. “A critic would have said ‘ah wonderful!’ I wanted honesty. I sat down and thought about who knows me best and I realized that it was the woman who gave birth to me and the man who has been working in my house for years.”

Sure enough, Shahid Shah, Waqas’ cook, finds a mention in Abstraction Contained (2012) where, describing the artist, he writes, “Either you are a lover of Allah or a psycho man… but, for me, your work is so deep.”

Indeed, when Waqas is at work in his studio, he straddles a thin line between spirituality and madness. It’s physically gruelling work – a man of his height and bulk hunched over a drawing board for hours on end, gripping the pen with both hands for accuracy. Yet there’s a meditative quality to it – he syncs his breathing in time with the strokes of the pen, the repetitiveness of the process often transporting him into a trance-like state.

The bigger works can take weeks, sometimes months, to complete, with Waqas hardly ever leaving the tranquility of his studio located above his house in Model Town, one of Lahore’s oldest residential neighbourhoods. It is the smaller works, however, that give him the freedom to connect with outside spaces. “When I travel, I make sure I keep a small drawing board handy and I sketch on it. These smaller works are really important to me because they are the keys on which I base my large drawings.”

Travel for Waqas can mean any one of these things – cycling around Model Town’s quiet streets early in the morning, catching a rickshaw to soak in the ancient architecture of the Shahi Hammam inside the Walled City, racing his jeep at Gilgit Baltistan’s spectacular cold desert, Sarfaranga, during a national car rally or escaping to his ancestral village for a few days of solitude. Of late though, most of his trips have taken him to international destinations – Manchester, Vienna and Paris to name the last few.

“I used to think that other places were different from Pakistan,” he muses on his recent trip to Manchester. “But I don’t think so anymore. Whether I’m in Lahore or Manchester, I take to the streets, I talk to people. I have made so many friends around the world by striking up random conversations.”

Photographer: Michael Pollard

Courtesy of Manchester Art Gallery, the artist and Sabrina Amrani Gallery

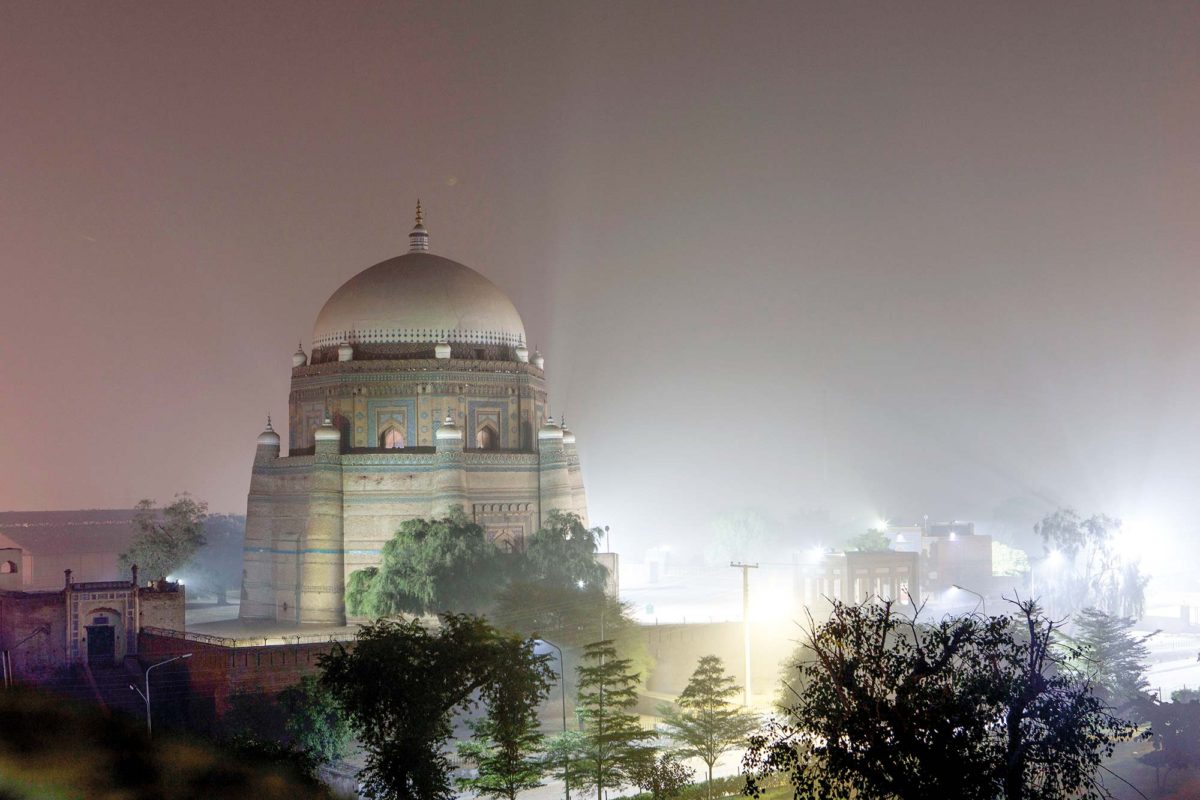

One such chance encounter led to a friendship that has spanned 5 years and two continents and is the reason why we’re navigating Old Lahore’s perilous traffic on a Sunday. During his 2012 residency in Vienna, Waqas met and befriended British artist William Mackrell and this fall, successfully managed to convince him to make the oft-talked about trip to Pakistan with his photographer girlfriend Agnese. Waqas, his wife Bushra and their 17-month-old son, Abdul Aziz have spent the day showing off their adopted city to the visitors, rounding up an eventful day of sightseeing with a tour of the Badshahi Mosque. Tomorrow, the group will head off to the countryside to be hosted by Bushra’s family at her village in Mianwali, enjoying a week of traditional rural hospitality.

Archival ink on wasli paper (diptych). 244 x 244 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Sabrina Amrani Gallery

As the sun dips below the horizon, we sit adjacent to the 17th century mosque’s sprawling courtyard, gazing up at a skyline dotted with some of Lahore’s most iconic buildings, sipping chai. “I used to come here with friends when I was in NCA,” recalls Waqas. “But I don’t think those people would recognize me anymore.” And who could blame them, for gone is the uninspired art student seeking distraction. In his place stands a man who is disciplined and at peace with himself, a man at the pinnacle of achieving greatness, worthy of being crowned Pakistan’s rising art star of the moment.

Archival ink on wasli paper (diptych). 70 x 102 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Sabrina Amrani Gallery

Archival ink on wasli paper. 244 x 132 cm

Photographer: Michael Pollard

Courtesy of Manchester Art Gallery, the artist and Sabrina Amrani Gallery

What the critics are saying…

“The visionary art of Waqas Khan has the power to lift you into a poetic paradise of shimmering lines in cosmic space. He is a true original, whose big, abstract drawings are as intricate as the structure of a leaf, as alive as water, as absorbing as a book. He lives and works in Lahore and this, his first solo show in a British gallery, is an unprecedented chance to explore his artistic magic in depth.” – Jonathan Jones, The Guardian

“… the religious and mystical power of his art is inescapable. That same spiritual intensity blazes in the paintings of Rothko and Mondrian – two great abstract artists with whom Khan, as his art grows in grandeur and complexity, deserves to be compared.” – Jonathan Jones, The Guardian

“As each piece demands your attention in the quietest way possible, the work is at once understated yet commanding — ensuring you experience the trance-like state of Khan’s work, rather than merely view it. Delirious and disorientating, each piece takes control of how you view it. The sweeping detail dictates how you must walk around it, negotiate it, and interact with it. You find yourself getting get right up close to it in wonder, urging yourself to find an imperfection, a mistake — but Khan has meticulous control.” – Cicely Ryder-Belson, The Mancunion

“Resistant to interpretation, sinews of incredible fluidity are accentuated by buoyant moments of rupture in the artist’s monochromatic abstractions. You can’t help but be pulled in. They are labours of love from the many hours, days and sometimes months spent hunched over his desk in Lahore.” – Christie Lee, COBO Social

“Waqas Khan does not offer any insights on how to navigate one’s way through the cryptic marks he offers up — marks which have expanded vigorously from their early diminutive beginnings. Coming across these secretive, somewhat tender accumulations of mark-making in 2009, one could only surmise that these were private communions that the artist was sharing for the first time. There was a shyness about the work which implied that Waqas Khan was as yet unsure about the veracity of his purpose. Yet the precision of the mark belied any self-doubt that may have lurked in the artist’s mind. The works spoke of an attentiveness to craft which invited the viewer’s focus.” – Salima Hashmi, Dawn

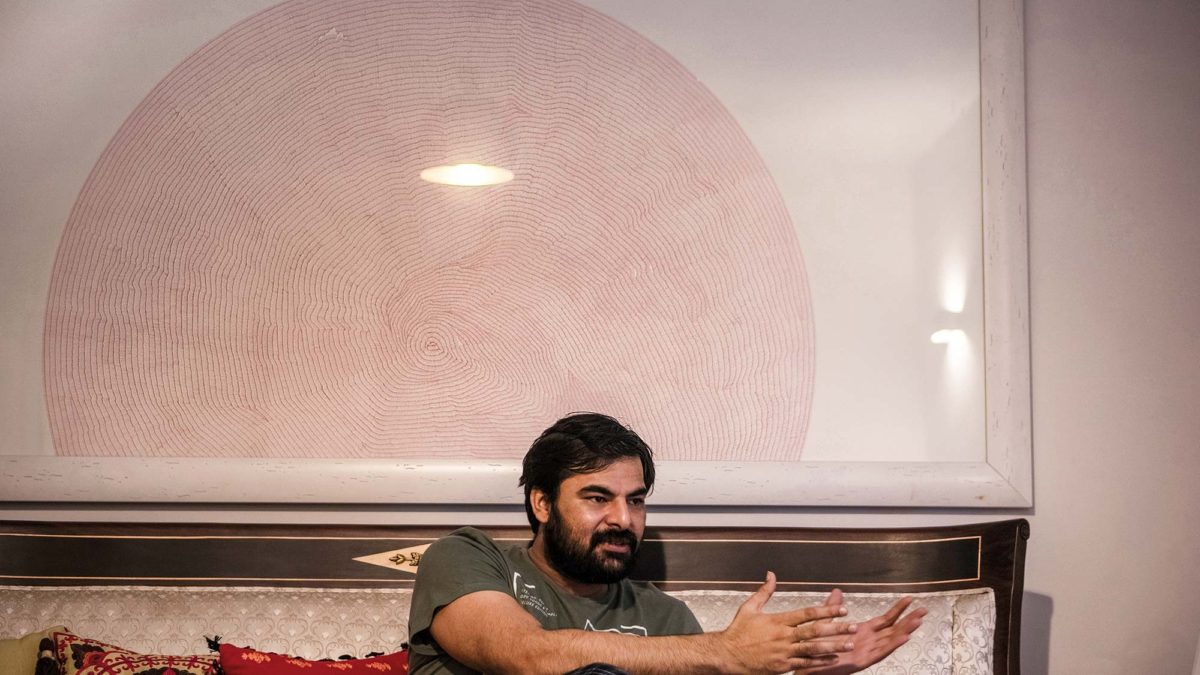

Waqas at his home and studio

Waqas on the road