Recently Siddharth and Lara Morakhia of the designer jewellery label “Lara Morakhia” made their way across the border from India to Pakistan to showcase their exclusive statement jewellery. During the course of their trip, they found themselves in Lahore, Karachi and Islamabad. Here’s a heartwarming account of their journey penned by Siddharth that details a narrative of pure love based on shared history and culture.

For all the shared history between India and Pakistan, it is strikingly odd that there are very few Indians who have seen Pakistan since partition and vice versa. In the absence of contact, the ideas of India and Pakistan tend to become grandiose hyperboles in our collective imaginations.

I have always wanted to visit Pakistan. I have wanted to see it for myself and develop my own judgements on the topic. Thus, when the chance to partner with my mother to showcase her elaborate, statement jewellery – under her brand Lara Morakhia – in Pakistan materialized, I could not miss the opportunity to embark on a trip of a lifetime.

I have never bought in to the idea of the perpetual animosity between the two countries. Rather, I have been captivated by our similarities and shared culture. For me, Pakistan has been and always will be a reflection of everything I am familiar with.

“How do you divide a soul?” – Fatima Bhutto on her journey from Lahore to Amritsar.

Wagah Border

60 kilometers separate the cities of Amritsar and Lahore. 60 kilometers separate India and Pakistan. In between runs a border that has fractured a soul. The notoriety of this border rests not in its at-present militarized nature, but rather in its everlasting ability to amplify insignificant differences and distort reflections in the process. For a barrier that stretches from the mountains of Kashmir to the humid shores of the Arabian Sea, there is perhaps only one point where the psychological damage of such a fracturing is manifest for public display: Wagah Border. Two gates, one either side of the “Zero Line” – the border between India and Pakistan – adorn the final one-kilometer stretch of the Grand Trunk Road between Amritsar and Lahore, forming the theatre of Wagah. There used to be a time when the Indian gate was crowned with a portrait of Gandhi, locked in an unwavering gaze with his counterpart, Mohammad Ali Jinnah on the Pakistani gate. How fitting it seemed that the two men from Gujarat who failed to see eye-to-eye on leadership of a free union were permanently locked in philosophical discourse to introspect (perhaps even, regret?) on their chosen courses of action. These days however, the Indians have put Gandhi out of his misery, erecting a stadium in place of his humble gate, and have left Jinnah with the awkward solitude of staring back at what he left behind.

As Punjab bakes under the retreating sun, the Pakistani Rangers and the Indian Border Security Force (BSF) perform the heavily choreographed gate-closing ceremony at the Zero Line. For those unfamiliar with the ceremony, the Rangers and BSF march towards the Zero Line in troupes and raise an outstretched leg to each other in a show of leashed antagonism. The more I look at it, self-contained in its own manufactured atmosphere complete with merchandise and snack vendors, the more absurd I find the entire ceremony becomes. Hostility, it seems, is the only accepted and encouraged form of normalcy between the two countries. The nauseating high-pitched ballads of yesteryear mixed with modern fist-pumping hits fill the air on the Indian-side as the crowd riles against the Great Enemy just beyond the border. Similarly, a lone performer on the Pakistani side, consumed in his own performance, stirs his crowd to jeer back at the Indians. Two reflections in dissonance.

“How is this normal?”

All the while, for the hundreds of spectators in presence, the gap between the gates provides the solitary vantage of a fractured soul—obscured only by the outstretched legs of the Pakistan Rangers and the Indian BSF. And then suddenly, in a complete break from the contrived aggression of the past hour, there is a wink, a smile, and a handshake between the two commanding performers. If you blink you miss it. The acknowledgement of the farce. The two pieces of the fractured soul touch, the gates close, and the reflections dissipate. Surely this cannot be real.

The Crossing

“Go through Wagah, it is the easiest. They are used to seeing people go back and forth”

Wagah Border during the day has a very different feel than Wagah Border at sundown. The general mood is somber and more in sync with the realities of political aggression. Nevertheless, while the theatrical atmosphere of the evening is missing, crossing the border is no less cinematic. Although it seems straightforward to follow the Grand Trunk Road straight through, a procedure that should take no longer than two minutes, there are instead a series of machinations in place that lengthen the process. On the Indian side, a heavy presence of camouflage is interspersed with stoic desk officers. It is evident, that unlike most shared border crossings on ground between two countries, there is no mutual communication between India and Pakistan. Nobody knows what to expect on or from the other side. The two countries and their procedures are completely isolated from each other. The removal of my SIM card on the suspicion of wire-tapping and a solider-accompanied bus ride to the Indian Gate increase the drama.

“Once you cross the Zero Line, you will be in Pakistan. We will not be able to help you from that point.”

Is this really happening? Lahore is just 30 kilometers away from these gates, but why is it meant to feel like it is a world away? The walk towards the Zero Line lacks public fanfare. There is no urgency; it is silent, empty and lonely – yet incredibly emotional. Each step becomes a step closer to the missing piece of an identity. The weight of our division becomes heavier as every second passes by. “We were all together once and we still have so much in common – how did we get to a point where seeing each other was such an ordeal?” And then suddenly, I snap back to reality as the porter helping me with my luggage stops. I am at the Zero Line. India ends here. Another porter from across the gate reaches across and pulls my bags through, and just like that, with one step, I am in Pakistan. A psychological divide breached. Joy, ecstasy, sorrow, relief. The missing piece – always so close and yet always so unattainable – is finally in grasp. What’s changed? For starters, I am thirty minutes back in time. But what else? What’s

really changed?

“Gandhi won’t work here. You’ll need Jinnahs. The going rate is…”

Immigrations and customs on the Pakistan side is surprisingly unfussed, with the exception of a 10-minute interrogation from an intelligence officer that is almost cinematic in nature. The purpose here is to verify that espionage is not part of my prescribed itinerary. The mistrust is palpable. But soon after, with paperwork in order, I am free.

Lahore

The drive from the border into Lahore, past the village of Wagah, is surreal. Have I really left Amritsar? It’s the same life, the same scenery emanating in every direction. The joint history is tangible. Is this what pre-partition India was like? I can’t help but reminisce to the now fading Golden Temple, whose foundation stone was laid by Sufi Mian Mir from the fast approaching Lahore. There is so much that is shared. It feels like I’m reading the missing pages of an incomplete story – like I’m finally seeing the chapter of Punjab unfold. How could you divide this place? How could you divide these people?

“This is not Lahore” – at least not anymore.

As Lahore city limits came to the fore, the rustic memories of rural Punjab quickly evaporate. Smooth wide roads, booming infrastructure projects, and high-end boutiques paint the surroundings distinctly urban. Forget Amritsar, have I just entered Delhi? I had heard before of the comparison of Lahore was to Delhi – the twins of the North – but I suppose I was not prepared for such an intense similarity. The look of the cities, the greenery, the bungalows, the food, the block malls, the history…it all just blends in.

“Is this Cantt. or is this Lutyens?”

While, in truth, I was conditioning myself to the nostalgic feel of the majestic Badshahi Masjid standing tall in the old city, the electric neighborhood of Gulberg was the most refreshing first stop after a long morning of border formalities. Lahore’s scene is here. Dotted amongst the shalvar-kameezes and dupattas, a younger and hipper Pakistan, with its overly-styled women and men with perfectly trimmed beards, makes its curated entry across the ubiquitous bourgeoisie cafes. For me, coming from Bombay, this “urban decay” felt wonderfully comfortable – so comfortable that although I let slip I was actually visiting from the Great Enemy beyond the border, nobody raised an eyebrow. I could be in Dubai for all I knew.

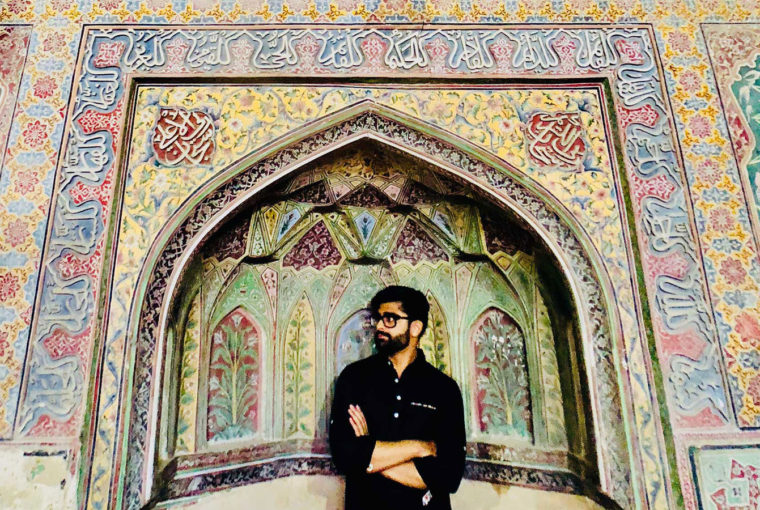

Lahore is an extraordinary tour-de-force; it has its own bold character and style. The city is modern, chic, and incredibly cultured. Even in the Androon Shehr, Lahoris have reinvented their surroundings to stay refreshingly relevant and also true to their storied past. The overwhelming beauty of the flamboyantly mosaiced Masjid Wazir Khan is one example. The elaborately colourful and ornate mosque is an oasis of peace that stands in self-imposed isolation from the world around it. Along with the equally enamouring Shahi Hamaam, the resonating Mughal architecture gives Lahore a distinct gravitas. Although I am seeing these structures for the first time, I can’t help but feel that I have been here before.

The barricading walls of Lahore Fort feel as welcoming as ever. I am uncharacteristically at ease in Lahore. I do not feel the discomfort of impolite stares or bustling crowds invading my personal space. Instead, I am able to control my own pace and craft my own experience and judgements. Lahore, much like Delhi, has an incredible history and a culture that blends and borrows from the Punjab. From the Dera Sahib Gurudwara standing proudly, almost hand-in-hand, with the Badshahi Masjid, to Nehru’s historic call for independence on the banks of the Ravi River, to Jinnah’s equally historic call for the creation of Pakistan – commemorated by the Minar-e-Pakistan, Lahore feels particularly grand, inviting all to write another chapter in its history.

One of my favourite Lahori moments takes place on the rooftop of the posh Andaaz restaurant, overlooking the majestic Badshahi Masjid. Shortly after the final azan call, the restaurant’s soundtrack switches to vintage Bollywood to set a mood befitting of a recently gentrified red-light district. Almost on cue, the suggestive Dum Maro Dum reaches the top of playlist and the high-pitched Hare Krishna Hare Rama chorus rings out over Lahore. Customers and wait-staff proceed to subconsciously hum along to the catchy tune. The grand Badshahi Masjid stands unperturbed as Lahore’s nightlife sparkles and reflects in the mosaics of the Sheesh Mahal and beyond. Lahore was in the mood to have a good time.

This is the curious case of India and Pakistan, why there are no other countries like them and why their division remains captivating. No matter how much you mix and match their core social fabric, their shared culture still prevails. These are two halves of a soul, almost yearning for each other, across an unnatural border.

Taxila, Katas Raj, and Islamabad

The drive from Lahore to Islamabad is stunning. Across five hours, lush Punjabi farms spread over the Chenab and Jhelum Rivers transform into the green hills and mountains of Kashmir. The drive is reminiscent of rural Switzerland in many ways considering the landscape, only more charming thanks to presence of some marvelous, eye-catching trucks and buses.

Along the way, tucked away in the Potohar Plateau, I find myself lost in the Katas Raj temples. This complex is one of Pakistan’s most colourful and fascinating mythological sights. As legend goes, the temples surround a pond created by the teardrops of the Hindu god Shiva, who roamed the Earth in grief after the death of his wife Sati. The temples of the complex themselves play significant roles in the Hindu Epic, Mahabharata. In present day, these structures are extremely peaceful and well-maintained. I can’t help but ask my guide if their presence has caused problems with locals after partition.

“Why would [the temples] cause problems? Ultimately, it is a place of worship and people respect that. We lived together before 1947.”

And perhaps, in that moment, the prejudices that conflict feeds us surfaced. The image of Pakistan consistently propagated is that of a place of fear and intolerance. Yet, every second I experienced here showed me the opposite – the epitome being a Muslim family from a nearby village who were excited to pray in a Shiva temple. What had changed since I crossed Wagah? This burgeoning question was harder to answer at every turn. Culture prevailed yet again.

Perhaps I would find the true roots of antagonism between Pakistan and India further north in Islamabad – the imposing capital territory that was frequently the source of fear in most of what Indian media reported. Yet again, however, my premonitions were wildly off-target.

“Islamabad? We prefer to call it Isloo up here…”

Isloo. I like Isloo – how could you not like a place called Isloo? I wonder if tensions between India and Pakistan could be downplayed if the media replaced the imposing “Islamabad” with “Isloo” in its reporting.

Nestled in the Margalla Hills, “Isloo” is a remarkably organized, well-planned and lush city sitting atop the garrison of Rawalpindi. As with Lahore, Islamabad showcases Pakistan’s beautiful cultural diversity in its own unique way: Punjabi mixes with Pathani mixes with Kashmiri. I have my first taste of gulabi Kashmiri chai here and I’m left wondering how this delicious concoction has been out of my mainstream for so long. Pile on a hearty serving of chapli kebabs in hill-top settings and what’s not to love about the immaculate Islamabad. While indeed, on surface-level, Islamabad is more reserved than its other Punjabi siblings, the capital territory has its wild side. As with any place, it is people that ultimately make moments special, and I was truly blessed to have my gracious hosts and dear friends hail from this unique citadel. On a lovely autumn night, when my hosts’ families and friends learnt I was visiting from the border across, they threw a party. Interest focused less on existing political stalemates and more on “the amazing time we had years ago at yoga retreats in the South of India.” Why did such charming memories between

us cease?

A stone’s throw away from the capital territory stand the deserted ruins of the Gandhara civilization, where Buddhism flourished in the region years before the introduction of monotheism. A small museum in the center of the city of Taxila now houses the astoundingly well-preserved Greco-Buddhist stone statues and reliefs found at the various archeological sites in the immediate vicinity. Rummaging through history, I paused by a small description under a carving labeled “The dream of Siddharth.” I couldn’t help but smile. Here was a sign that quite literally took stock of an increasingly endearing experience in Pakistan.

Karachi

The descent from the lush greenery of the Punjab to the dun-coloured Sindh is a welcome shock to the system. Throwing all caution to wind, I enter a boiling-pot of a city on the shores of the Arabian Sea. Karachi, the old capital long since shunned for northern pastures, is maddeningly diverse, hot, chaotic, and disorganized. Karachi is the rebellious, misbehaving, and brash sibling to Lahore; Karachi is everything that Lahore is not, and as much as I love Lahore, I find Karachi perfectly embodies modern and urban Pakistan.

“What am I going to do here? Everything.”

While Karachi may not offer many instagrammable touristic sights, the city offers a jaw-droppingly eclectic vibe—if you can find it. Hidden amongst the extravagant bungalows in Clifton and Defense, Karachi has an incredibly urban scene behind closed doors. My first night took me to the uberhip AAN Gandhara Art Space. Everything changed here. The formality bound to Lahore and Islamabad gave way to a casual and inviting coolness as the showcased artists gushed about their metaphysical inspirations.

In almost every observable aspect of life, Karachi commands its own style. The refined Urdu of the north starts to mix with English, Pathani (Pashto) Sindhi and everything in between. Ripped jeans and cocktail rompers replace the uniform-like salvars. Even though I had barely just made headway in the city, Karachi felt like home. There is a political incorrectness in this city that transcends nationality. The attitudes of Karachi are whole-and-soul the property of Karachiites – nobody has the power to tell a Karachiite how to behave or what to think. Put simply, Karachiites do whatever they want to do.

Just as Lahore and Delhi are fused at the hip, so too are Karachi and Bombay. The free-spirited mentality of the two cities is eerily similar and I find it incredibly fascinating that Karachi is perhaps more synchronized with Bombay than it is with Lahore. How a billion-plus people that have so much in common are kept apart is baffling.

Leaving Pakistan

“This is Wagah Border, where do you think you are going, India?”

I found leaving Pakistan to be an extremely saddening experience. I was leaving a place that was too familiar, I was leaving people that I had far too much in common with, I was leaving something I ultimately loved without the guarantee of returning.

Pakistan and India are two sides of the same coin. The politics that scrutinize our differences fail to recognize the mutual love and culture shared by the people. Our souls are magnetic, there is a universal attraction that seems to overcome every wedge driven between us. We are meant to be together and I encourage all to cross the divide if the opportunity arises. Pakistan is a beautiful place with equally lovely people. The line and its subsequent machinations that keep us separated are unnatural. As I made the lonely trek back to Wagah Border, I found myself asking the same question I had been asking before I entered Pakistan.

How do you divide a soul?The Answer: You can’t.