The Shahi Hammam, a 17th century public bathhouse dating back to the reign of Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, is one of Lahore’s most spectacular historical monuments. In 2013, the Walled City of Lahore Authority (WCLA), in partnership with the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, undertook the conservation of this ancient building that was suffering from neglect and it now stands restored to its former glory, a feat of design and engineering that reflects the Mughal era’s cultural richness.

Ancient legend has it that the king who defeated and finally killed the mighty Mongol Changez Khan, Veer Dada Jashraj, was born here in Lohargadh, as it was known back then. Old Lahore, or the Walled City as it now known, is a cultural hotspot in the historical landscape of Pakistan. While myths and legends abound regarding the actual history of this 2.6 kilometre city state, architectural marvels from hundreds of years ago lay testament to the glory of its past. Passing hands between Hindu, Muslim and Sikh rulers, most of the town structures contained within its 13 gates are design gems that reflect a foregone era of cultural richness and financial prosperity. Intricately carved wooden balconies, cobbled streets, grand monuments, ancestral havelis, the food and festivals, the hustle and bustle of the bazaars all lead one back into a past when the Walled City of Lahore was the prime hub of culture and trade.

Having served as the capital seat for numerous empires, the city demands more than a mere perambulation if one is to explore the tradition and folklore it holds within its historical walls.

It was on one such expedition, during a photo walk inside Delhi Gate a few years ago, that I first came across the Shahi Hammam. I was quite taken aback by my lack of knowledge regarding this unique piece of heritage we possess. Although remains found in the Lahore Fort, the Shalimar Gardens, Wah Gardens and some of the larger havelis in the Walled City indicate that smaller, private baths may have been popular during the Mughal and Sikh eras, this royal monument is the only structural bathhouse from the Mughal era that continues to survive in the entire Indian subcontinent.

During its history, the building was converted into a boys’ primary school, a girls’ vocational school, a dispensary and was used as offices by various government departments. Makeshift structures, to provide residential accommodation for some of the staff, were added on the roof. The north-western rooms were rented out as shops by the Department of Auqaf while additional shops were allowed along the building’s northern, western and southern façades. These occupations resulted in the structure of the hammam being subjected to numerous alterations and modifications without any regard to its historic or cultural sanctity, besides leaving it without proper maintenance and upkeep. Lack of maintenance also resulted in the deterioration of the building. It was not until 1955 that the Shahi Hammam was recognized as a cultural asset and declared a protected monument by the Department of Archaeology.

In 2012, the Walled City of Lahore Authority (WCLA) took over the restoration of the Shahi Hammam as part of The Royal Trail Project, carried out in partnership with the Aga Khan Trust for Culture. Within three years, the ancient bathhouse stood restored to its former grandeur.

As one crosses mounds of colour in varying degrees through Akbari Mandi, a historical spice bazaar set up by Mughal Emperor Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar (1542-1605) that continues to serve its original purpose to this day, and passes through Delhi Gate, a security landmark also built by Emperor Akbar, a small inroad towards the left will lead you to a side entrance of the Shahi Hammam.

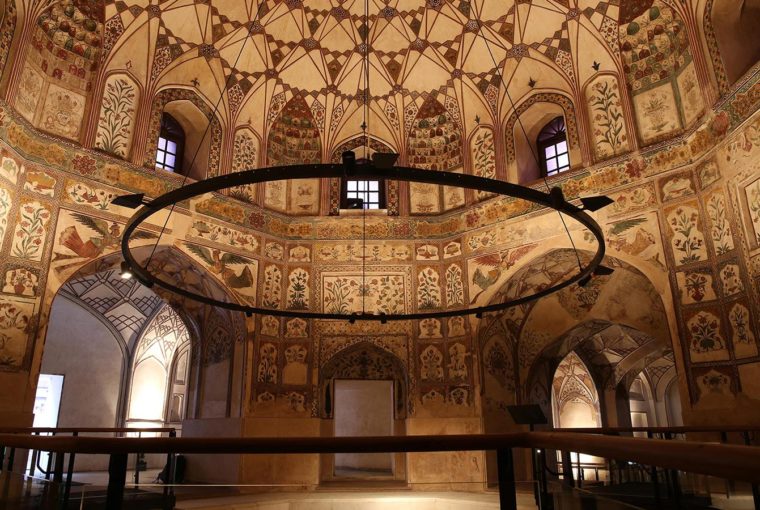

Upon entering the hall, one is astounded by the quiet elegance and regal splendour of the space. The vibrant colours of painted fresco serve as a gentle reminder of the rich opulence of Mughal architecture. As a photographer and a visual artist, I found it difficult to pull my eyes away from this surviving marvel that transports one back into a time when this region was amongst the most splendid in the world – when the magnificence of the Mughals outshone the brilliance of the outside world.

An engraved plaque near the entrance reads as follows: “The Shahi Hammam was originally built around 1634 AD by Hakim Ilmuddin Ansari, the Governor of Lahore, during the reign of Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan (r. 1628-58 AD). It was designed as a public bath for the travellers as well as the inhabitants of the city køb viagra. Hakim Ilmuddin Ansari, who was granted the title of Wazir Khan, was also responsible for the construction of the famous mosque The Wazir Khan Mosque inside the Walled City which now bears his name.”

The hammam is a single storey structure covering an area of 1110 square meters, built on the pattern of Turkish and Iranian bathing establishments of its time (which consisted of hot, warm and cool plunges, sweat rooms and related facilities). Designed as a public bathhouse not only for the inhabitants of the city but also for travellers visiting it, the monument serves as an example of a Mughal community space that provided opportunities for social interaction in the lives of the citizens. Travellers would enter Lahore via Delhi Gate and would freshen up at the hammam, before continuing onwards into the city.

It is a collection of 21 inter-connected rooms offering all the facilities found in a public bath. An additional room is set at an angle facing Mecca for offering prayers. The entrance gateway on the west and the main hall in the northern part of the building are exquisitely decorated with frescoed panels depicting angels, animals, birds as well as floral patterns and geometric designs.

Tourist guidebooks available inside the hammam outline its unique form and function, explaining how wood logs were used to heat water and convert it to steam which then passed through pillars or channels and heated up the entire place. This expansive heating system was destroyed during the Sikh rule.

WCLA, with the help of the Aga Khan Cultural Services Pakistan and in collaboration with the Royal Norwegian Embassy, carried out extensive restoration works for the exposure and display of the original waterworks, drainage and heating networks, as well as the levelling of the original floor that had been covered over in 1991.

On the western side, the hammam’s original entrance has also been restored, through which the bathhouse is accessible now. The centuries-old frescoes inside the Hammam have been cleared and restored with the help of fresco conservation experts from Sri Lanka.

I had the good fortune of meeting the team in charge of the conservation project while it was being restored. I was informed that the aim for the conserved monument was not only to serve as a display of the ancient tradition of public bathhouses as a space for social interaction, but also to extend it as a space for promoting art, culture and literature through hosting talks, art exhibits, poetry recitations and traditional story-telling activities.

Looking at the newly restored interiors of the splendid structure fills one with awe and wonder at this ancient design and engineering feat, a feeling of pride and honour for our association with its history and culture and a deep sense of responsibility and ownership for preserving this spectacle for generations to come.