Eight kilometres south of main Shahi Qila Chowk, the crowded streets of Hyderabad, teeming with rickshaws, cars and motorbikes, converge on to a cloth market that is much like any bazaar you would find elsewhere in the country – a collection of concrete buildings with apartments on the top floors and tiny shops along the street, displaying their merchandise on the footpath. Swathes of embroidered cloth flutter in the humid air while Chinese imports of cosmetics and accessories beckon luridly.

The pedestrian streets weaving through the market are not meant for vehicular traffic; my rickshaw driver deposits me a few blocks away and I complete the remainder of the distance on foot. The cloth market itself might be unremarkable but tucked within its depth is a unique landmark; and it is to photograph this marvel that I’ve undertaken the journey from my hometown Karachi despite the sweltering heat.

Amidst the congested stalls of the cloth bazaar, a tiny entrance leads to a narrow alley. There is no signboard and none is needed; just ask for ‘Choori Gali’ (Bangle Market) and dozens of hands will lift to point you in the right direction. Row upon row of glittering bangles, in a mind-boggling array of colours and styles, greet me as I step inside the Choori Gali. The salesmen, lolling around shop fronts and engaging in banter given the lack of customers this early in the morning, suddenly snap to attention. “Aajai, baithay (come, sit),” they beckon, pointing to their display of beautiful ornaments set up behind glass counters. It doesn’t matter if you are a man or a woman; they seek everyone as a potential customer.

Hyderabad, Pakistan’s fourth largest city, is known for its handmade products but perhaps none define it better than bangles – that glittering ornament that no South Asian festivity is complete without. The city’s Choori Gali or Bangle Market is the largest wholesale bazaar of its kind in the country, consisting not only of shops selling the product but a huge network of manufacturing and designs units that produce bangles known for their high quality all over Pakistan.

The retail side of the market is primarily the narrow alley through which I entered, with around thirty shops on either side. Business is slow in the mornings, given the high temperatures that hit Hyderabad but once the sun goes down and the weather takes a turn for the better, shoppers begin to crowd around the colourful displays. “Men and women both are our customers. The men buy for their wives or sisters who cannot make it to the market while our primary costumers are women,” says Mohammad Ayub, who owns a small shop in the market.

Walking down the street, I am greeted by the tantalizing aroma of samosas and pakoras being fried next to tea-stalls and eventually exit into an open area flanked by buildings that house the small factories.

Unlike the shopping street, this part of the bazaar is characterized by frenzied activity. Men of all ages are busy at work. I barely move out of the way as a four-wheeled cart loaded with bundles of bangles lumbers down the path. Nearby, a teenaged boy whistles loudly to signal his approaching arrival as he carries glass bangles threaded into a rope. Trucks stand ready in the centre of the square, loaded with boxes that are to be sent to other parts of the country. This bustle continues throughout the day.

The smell I encounter here is unlike the familiar aroma of fried delicacies I had chanced upon earlier; it is pungent and chemical in nature. The source, I discover, is the ‘liquid gold’ that is being used by artisans to coat the glass bangles. The known history of bangles as a form of ornamentation can be dated back to 5,000 years ago, based on the remains of a dancing girl statute found at a Mohenjodaro excavation site in Sindh. The modern-day glass bangle, however, began manufacturing around a hundred years ago in a small town called Firozabad in Uttar Pradesh, India. After partition, many of the craftsmen and artisans who were part of the bangle industry migrated to Pakistan and settled in Hyderabad.

One of them was a man named Rustum Ustad, not only a craftsman par excellence but also a shrewd businessman. He can be credited for initiating the bangle-producing industry in Hyderabad, for he was the first of Firozabad’s artisans to set up production in the new country. His grandson, Azhar Hussain Siddique, is currently the representative of the union office of the Bangle Market.

“There are around 2,000 shops in the area that are associated with bangle production,” says Azhar. “When my father started off, there were only about ten shops here but now close to twenty hundred thousand men and women in Hyderabad are associated with the work.”

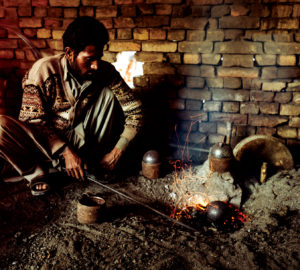

The sound of tinkling glass holds my attention and I look around to see a few workers huddled around a small glass bottle. They take a bangle and hit it on the bottle and based on the sound it makes, can tell if the bangle is broken or intact. The ones deemed fit for further processing are coated with the liquid gold by artisans who use special brushes to create intricate designs.

From here, they are carted off to the furnace factories located right behind the market where the bangles are arranged in a single layer and ‘baked’ inside huge ovens to give the liquid gold a desired temperature, whereby it attains its original glittering sheen. “The production cycle of the bangle, from manufacturing to retail, goes through 20 to 30 stages depending on style and design,” reveals Azhar.

“We get plain bangles from the factories, we sort them out by weight and size, take them for cutting and design work and then sell them in the wholesale market,” says Khalid Raza Mirza, who runs a small wholesale business in the market.

Khalid is well-versed in the trade, for he has been a bangle-seller all his life. It’s what he grew up seeing his father do as well. “I have seen a lot of changes in the business for the years. Now we have modern machinery to make the bangles which has increased production rates,” he says. “It used to be manual till a few years ago, but technology has made it easier and also more innovative. We have machines that can emboss different patterns and designs on bangles,” he adds.

Since bangles are favoured by women during all festive occasions – be it weddings, parties or Eid – the business runs throughout the year, though peak times are usually before the festivals of Eid or during December, which is wedding season. The salesmen particularly look forward to the month of Ramazan, especially the days after the tenth roza, as Eid shopping reaches a frantic pace and women crowd the market looking for the perfect accessory to match their Eid finery. “The market is open throughout the night on Chand Raat and that’s when we make the most sales,” says Khalid.

I am told that the latest trend in bangle-design is to have the wearer’s name engraved on the ornament and these are favoured particularly during weddings. Such designs are made only on special order, though. The more traditional types of bangles are the Sath Rangi (seven coloured) or Panch Rangi (five coloured).

By now the sun is setting and the market has lit up, making its displays look even more vibrant. Shoppers start to trickle in as I head out, the images of the colourful and festive chooriyan fresh in my mind.

Comments are closed.