Peshawar is Pakistan’s oldest living city. Much of its history remains shrouded in clouds of dust revved up by the hooves of conquering forces and centuries of political upheaval. At the heart of it all is the city of flowers that retains its mystique in crowded bazaars, in qehvakhanas and in caravanserais that homed many a weary traveller. Explorer and travel writer Salman Rashid narrates a compelling tale as he weaves through 2500 years of its recorded history, noting down conquests and observations made by famous historical figures through time.

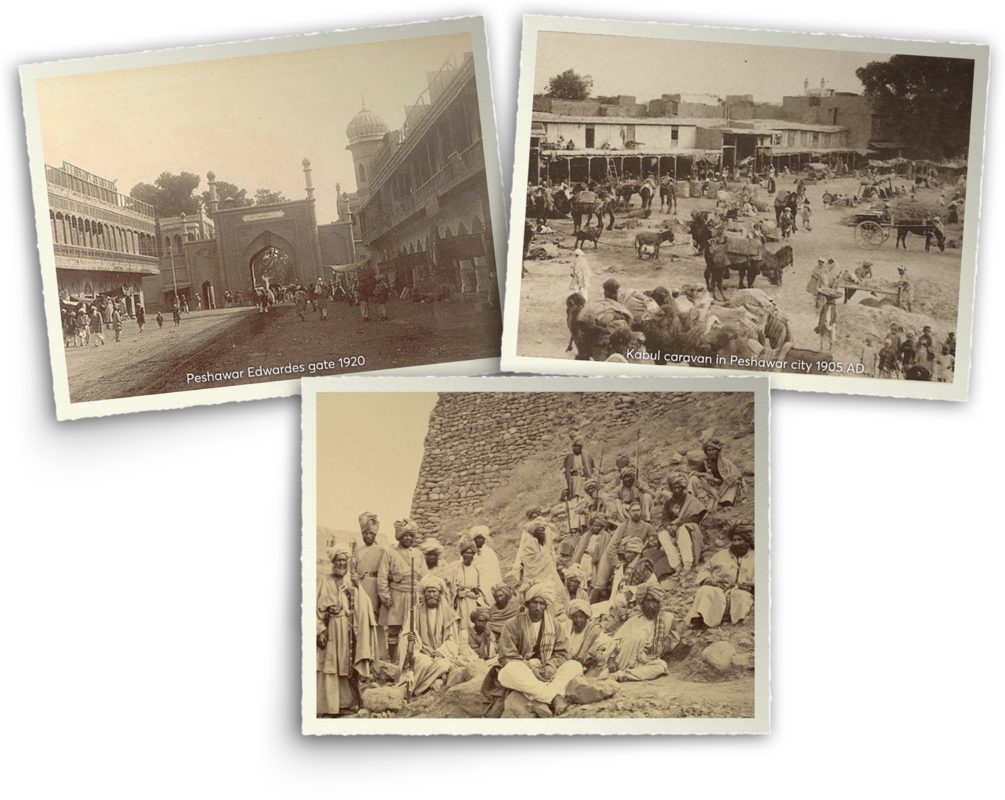

Peshawar is not about the clatter of armoury, the tramp of soldiers’ feet and the raging din of battle; it is not of a city on fire and the cries of the dying. Peshawar is about murmured prayer, of the ringing of the temple bell and the call from the minaret, the clang of the jaras – the bell around the camel’s neck in the caravan – and the soft plop of the animals’ feet on unpaved streets, it is of the vendor crying his wares in streets where rows of shops run on either side and which are crowded with buyers and sellers. Peshawar is about long distance travellers, of caravanserais and story-tellers.

It was April 1977, and I was wandering about Namak Mandi in Ander Shehr (Inner City) Peshawar. In a narrow street lined with stores and qehvakhanas, it leapt straight out of a story-teller’s repertoire: the caravanserai with its open-to-the-sky courtyard and spacious rooms on all four sides. A timber staircase led to the floor above where smaller rooms were equipped with fireplaces. But in 1977, the fireplaces were cold, the rooms empty and dusty, unused for perhaps a couple of decades and the downstairs rooms served as warehouse for packaged goods.

The men working in the warehouse did not mind my pottering around and in those few minutes I was taken back through the centuries. I saw the caravans work their way along the street, the camels – all double-humped Bactrians – coming through the high gateway of the sarai and crouched in the courtyard to be unloaded. The travellers, dusty and tired, wishing only the bath and then the tryst with the story-tellers of the nearby bazaar. There, after the meal, the tales would flow over endless cups of qehva. Peshawar was the stuff of stories written centuries before our time.

By all accounts, the city’s ancient name was Pushpapura – City of Flowers. Two thousand years after being bestowed this beautiful title, Pushpapura enthralled Babur. In 1504, the first Mughal king of India: waxing eloquent, recounts the colours of the flowers grown in plots to ‘form a sextuple’. Here ‘as far as the eye reached, flowers were in bloom’. He concluded that in spring the fields near the city were truly beautiful with blossoms of every colour.

THE REAL STORY OF PESHAWAR

In the year BCE 520, Skylax, the sea captain from Karyanda, mispronouced the name of the city. Commissioned by Darius the Great of Persia to map the Indus River, Skylax set down the Kabul River near the city he calls Kaspatyrus. His work, cited by later Greek and Roman authors, is lost and we know of no other detail the explorer noted on the city.

Shortly after Skylax’s reconnaissance, by BCE 515 Darius annexed all of what is now Pakistan to his empire. And so, Peshawar together with the rest of the country became a tribute payer to the King of Kings. Two centuries of peace ensued and here in Peshawar followers of the new religion of Buddha lived besides singers of Vedic hymns and followers of Zoroaster.

In BCE 326, Alexander’s generals Krateros and Haphaestion brought down through Khyber Pass two divisions of the army and rested a few days in Peshawar. The Greeks were as tolerant of different beliefs as their predecessors and even if the governor was changed, life went on undisturbed.

But Alexander’s kingdom was short-lived. No sooner had his body lost the colour of life in distant Babylon, there began the great struggle among his generals to be ‘the strongest’. That is what the comatose king had said when his generals asked him who the kingdom would go to. The Greek governor left Peshawar to find his fortune in that struggle and Chandragupta Maurya took control of the country. The year was BCE 322.

Even if Chandragupta and his grandson Asoka are celebrated for the brilliance of their rule, it is only the nature of empires to decay. The fall of the Mauryan Empire gave way to the Greeks whose grandsires had first entered India with Alexander. Having taken over Afghanistan, the Indo-Greeks, as historians today refer to them, established themselves by BCE 180 over much of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab. This was only the beginning of the great pageant of dynasties that ruled over the City of Flowers.

The Greeks gave way to the Persian speaking Parthians who were supplanted by gold-wearing Scythians who, in turn, succumbed to the Kushans under the brilliant builder Kanishka (c. 127- 150 CE). Noted as the greatest among the Kushan kings, Kanishka ordered the building of one huge stupa said to be no less than a hundred and twenty metres tall (an obvious exaggeration). According to prominent Chinese pilgrims and Buddhists of the time, beside this towering edifice, a smaller one appeared miraculously after the main dome was raised. They record that on his visit to Peshawar, Buddha had foretold not only the name of Kanishka but also that he would build a stupa and a monastery.

By the end of the 3rd century of the Common Era, the wheel turned full circle to the Persians, now it was the Sassanian dynasty.

In the early 5th century (CE 400), Fa Hian, the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim, arrived in the city he called Purushapura. Kanishka had been dead for over two centuries, but he noted that his magnificent stupa was almost as good as new and it was the centre to which every Buddhist gravitated.

In the last quarter of the 5th century, the savage Huns poured down the western passes to ravage Peshawar. And if the great Buddha had indeed said that the stupa to be built by the pious Kanishka would be destroyed seven times and rebuilt, the first devastation was upon it. Without remorse and without regard for woman, man or child, the Huns, first under Tor Aman and then his son Mehr Gul, raped, killed and sacked. In centuries of political upheaval, Peshawar had seen a few battles, but never such wanton brutality and destruction. The city was left a smouldering ruin.

A hundred years later, in CE 518, came the famous Chinese pilgrim, Sung Yun, who lamented the ‘most barbarous atrocities’ of the ‘cruel and vindictive’ Mehr Gul passing only a hundred years before his time. He too stood before the great stupa in silent prayer with folded hands and told us that a pipal tree shading the stupa with ‘thick foliage’ was the very one the great Kanishka had himself planted.

No sooner had the barbarians passed on to the east to be finally defeated by a confederacy of Rajputs in Cholistan in CE 528, Peshawar rebounded. Once again trading caravans came down the Khyber; the bazaars thronged, the story-tellers regaled their audiences and the flowers grew. Once again peace returned to Peshawar, this time for five hundred years.

In the year CE 631, Peshawar was visited the most celebrated Buddhist teacher Xuanzang. He described the gilded dome of the main stupa and mentioned a hundred other stupas surrounding it. He also noticed the pipal tree which would now have been over four hundred years old. Buddhism, the master lamented, was on the decline and the monastery in decay, however.

That all these luminaries setting out of China on their quest for the true word of the great Buddha in India came through Purushapura tells us that the city lay on a major travel route. As the great trans-Asian highway now called the Silk Road dipped down from Samarkand to cross the Hindu Kush Mountains into Kabul, it extended eastward across the barren rocks of the Khyber Pass to make Peshawar.

In these years of peace in the Khyber Pass, the powerful Hindu Shahya rulers of Kashmir extended their sway through Peshawar to Kabul and all remained well. Now amid the ruins of Kanishka’s monastery, the sound of Buddhist hymns gave way to the Vedic.

And then in the closing years of the 10th century came the plundering Turks. After the initial excursions of Subuktagin, his son Mahmood was unstoppable. Ostensibly driven to spread the glory of Islam to heathen India, the man was in reality a common robber with his eye on the wealth of the subcontinent and Peshawar suffered greatly. In time, however, the city came to be spared vengefulness because of the growing number of Muslims among its populace.

Thereafter were another five hundred years of repeated upheavals as the Ghaznavides gave way to the Slave Dynasty, then briefly the Mongols and, from the early 16th century, the Mughals.

In the Middle Ages, the flowers of the city may have already been celebrated, but now the road-weary travellers were only intent on reaching India, the land of culture, learning and wealth untold. The City of Flowers became Pesh-Awar – the First Comer – the first city of the subcontinent.

On his first visit to Parshawar, Babur, the founder and first Emperor of the Mughal Empire, divulges something very interesting: tales of Gorkhatri had been told him and that it was a ‘holy place of jogis and Hindus who came from far places to shave their heads and beards there.” Gorkhatri, signifying House of the Hindu, was located in the precinct of Begram in the city. Thence he rode from his camp at Jamrud. He toured the place and even remarked on the ‘great tree’, surely the very one Kanishka had planted nearly thirteen centuries earlier and which the Chinese pilgrims had marvelled on. But our warrior poet made no mention of the great stupa. That the place was now called House of the Hindu shows that by this time Buddhism was all but forgotten in these parts.

But Babur found nothing of interest. His guide, Abu Said, thinking his esteemed guest would find the dark and the cramped space unsavoury did not show Babur the underground vaults. When, back in Jamrud, Babur complained about uninteresting Gorkhatri, the guide confessed he had on purpose not shown him the vaults because of the difficulty of getting into them which. The man was roundly upbraided, but as the way back was long and the day almost over, Babur deferred the dungeons for a subsequent visit.

In March 1519, on his way to establish the Mughal Empire in India, Babur paused at Gorkhatri, ‘a smallish abode’ much like a hermitage. All around was a large number of smaller cells as in a Buddhist monastery recalling the time when it was indeed that. Holding a lamp, he crawled on all fours into the dark oubliette through a mess of human hair. The man was disgusted. He recalled his earlier visit and how he had rued being denied a peek. Now he wryly noted, ‘but it does not seem a place to regret not seeing.’

After the decay of the Mughal Empire, the Turk Nadir Shah of Persia set his eyes on its wealth and mounted repeated incursions on this land. Peace finally returned with Ranjit Singh’s reign as the Khalsas took over.

THE WALL OF PESHAWAR’S SPOKEN WORD, BRICK BY BRICK

Peshawar was never a city of Pakhtuns who spoke a language rising out of ancient Avestan. It was a city of traders, professionals and scholars who spoke a language derived from Punjabi and Kashmiri with a sprinkling of Gujarati from a long way off to the south. Even in the Middle Ages, natives of Pushpapura would have been surnamed Chawla or Arora or Piracha rather than Afridi or Yusufzai. Sometime after the Pakhtuns converted to Islam, the language of Peshawar and indeed of other cities of the province came to be known as Hindko after the largely Hindu population.

As a city whose businessmen dealt with traders from distant lands, Peshawar was multi-lingual. The Hindko speaker was equally comfortable in the Pashto of the man come down from the Khyber defiles or from Waziristan as he was in Uzbek or a couple of other Turkish dialects.

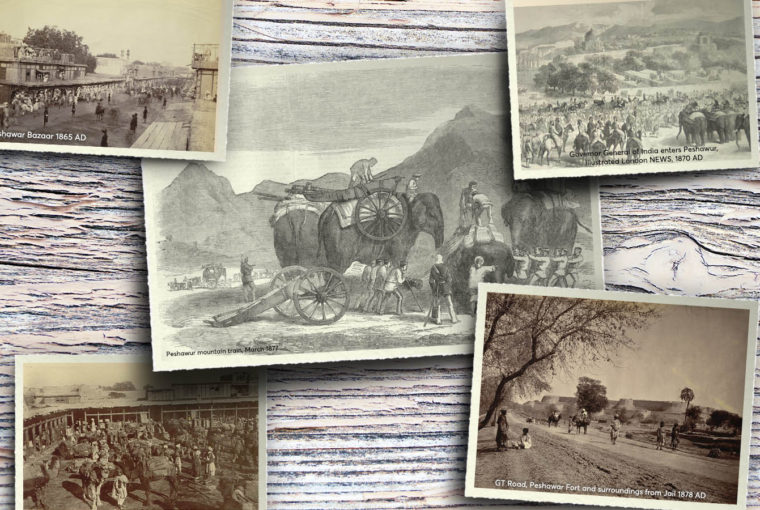

PESHAWAR, UNDER THE BRITISH RAJ

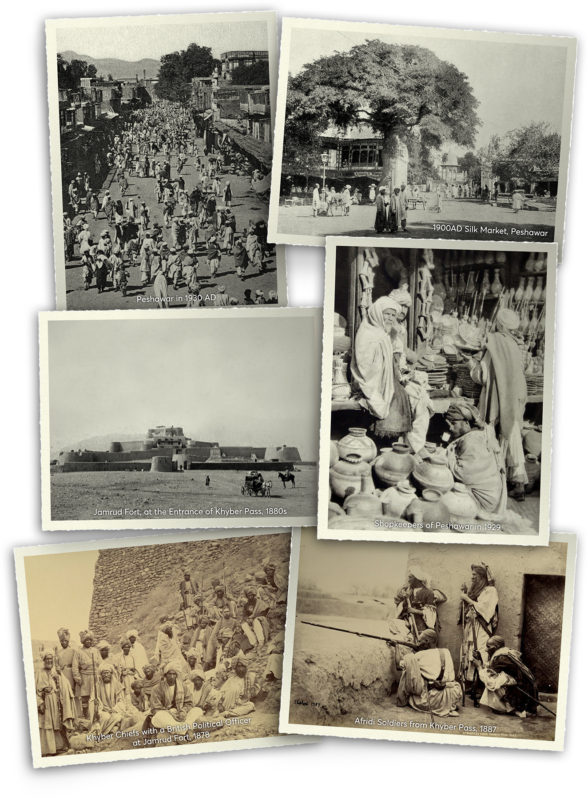

That is how British administrators of the East India Company found the city in the mid-19th century. It was an island of peaceful businesspeople surrounded by a host, staunchly religious, sometimes peaceful and friendly, otherwise turbulent and troublesome. They could be seen swaggering about in their large turbans, baggy shalwars and flowing collar-less kurtas with a tassel, rather than buttons, on the side to tie as they did business with the dhoti-clad storekeeper.

Upon taking over, the British repaired the old fort and set about constructing a cantonment. Among the earliest buildings was the deputy commissioner’s residence built in 1849. On a natural mound that very likely conceals the remains of an ancient past, they raised an edifice that was a clean break from the traditional fortified houses of tribal chiefs just outside the cantonment.

Visiting Pakhtun dignitaries would surely have found madness in the exposed veranda and the absence of crenulations or loopholes along the parapet of the building. It was either that or some hidden strength they failed to see. Whatever was thought of it, the administrators did not change the building. It was only added to and it eventually became the Governor House.

LIFE BEFORE 1979

Even as the British built their churches, mission schools and the Saddar Bazaar, life in the old city remained unchanged. And so it continued to 1977 when I first became acquainted with Peshawar as a grown up. It was a city to fall in love with. The flowers that Babur had exulted over were everywhere: in parks, in every private garden, in the sprawling grounds of Islamia College and even along the roads and amid the tombstones of the Christian cemetery. In spring when the millions of roses were in full bloom in Peshawar, the city was swamped with fragrance and I wanted to call it The Rosary: for if a vine-growing orchard is a vinery, surely a city of roses was a Rosary.

Though there were no double-humped camels plodding in with their loads from the marts of Samarkand and Fergana, the bazaars somehow retained the ageless colour. In open-fronted stores, the gentleman shopkeeper with his dark vest and karakul cap leaned forward to speak softly to the Khan from some village in Tirah or deeper still from the land of the Orakzais. You could tell the visitor was a Khan for his chin was clean-shaven, his moustaches neatly trimmed, his shalwar kameez crisp and he too wore the dark vest and karakul hat. But he also carried his pistol and a belt full of ammo slung across his shoulders.

They could well be talking of the next crop of maize to be brought in from the uplands or the set of copperware needed for a wedding in the Khan’s family, but the very air of frontier town Peshawar made me feel they were conspiring. The bazaars of Ander Shehr (inner city) were replete with scenes from an imagination honed by Kipling.

The air was so clean, that in the winter of ’77 when it rained in Peshawar, we could espy new snow on the hills of Landi Kotal. Peshawar was just like that when I left it in August 1978 telling my friends I would come to live here when I retired.

LIFE AFTER 1979

I returned in 1985. It was as if centuries had affected the huge change. Countless boxy vans with ‘TRP’ registration plates emitting dark clouds of smoke drove roughshod around the city. Boy conductors shouted in the Kabul dialect of Pashto (sometimes in Dari) to draw commuters and there were Afghans everywhere. They were either ‘mujahedeen’ or refugees. But they altered the personality of Peshawar. It was no longer the city I wanted to retire to.

Five years ago, my friend Dr Syed Amjad Hussain who migrated decades ago from his Meena Bazaar home in the city to Boston, took me walkabout in the old streets. We ended up at the excavation near Gorkhatri. There we stood looking down the pit into the layers of habitation spread across two and a half millenniums. They were all there: the Persian Achaemenian, Punjabi Mauryan, Greek, Parthian, Scythian, Kushan, Sassanian, Hun, Hindu Shahya, Ghaznavide, Ghorid, Mughals and Sikh.

The archaeologists at hand said there were layers below the bottom and boasted that Peshawar was the oldest living city of Pakistan. I knew it was no empty brag. No matter what they said about Lahore, those of us who have read their ancient geography and history know that Lahore was a city only when Peshawar was already fifteen hundred years old.

If Peshawar could live through all the upheavals that the layers of cultural remains show in the Gorkhatri excavation, surely it can come out of the damage inflicted upon its soul in the years during and after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Call it what you will: Pushpapura, Kaspatyrus, Purushapura (from which our pious Chinese called it Po-lu-sha-pu-lo), Parshawar or Peshawar, its flowers still bloom and channel their fragrance.

Peshawar will come through for it is still the City of Flowers.