The Mayo Hospital in Lahore is wearing a new look – the original one. As one walks into the main building of this historic hospital, one is taken back in time; to the 19th century, when the hospital was built and named after then Viceroy of British India, Richard Bourke, 6th Earl of Mayo. Now a teaching hospital attached with the best medical school in the city, King Edward Medical University, it was seen that in the recent decades the place had lost much of its original character and architectural appeal as it suffered the blows of time, high turnover of patients, dwindling health care funds from the government and a general lack of care.

In fact in 2013, the government decided to demolish the century-old Newton Hall for road widening. In recognition of its key historical value, one of the trustees of the hospital, entrepreneur and philanthropist, Iqbal Z Ahmed discussed his concerns with his son, Attiq Ahmed. Principal Architect and Chief Executive of Lahore’s leading architectural firm, AEDL, Ahmed is also a bonafide Lahori and a creative force who draws major inspiration from his hometown.

The firm ended up not only saving the main building but managed to map out the entire 50 acre property and survey its circulation flows in a bid to prevent the slated demolition and propose improvements.

Four years later, Ahmed and his firm AEDL were approached by Lahore’s chief architect, Nayyar Ali Dada to present their original work to the newly formed NGO, Friends of Mayo Hospital of which he was a board member, with the aim to to restore and rehabilitate the hospital’s architectural integrity and give it a social uplift via a series of significant structural renovations. The firm won the project and the rest as they say is history.

Tell us how this project came about? When did you start working on it? And what inspired you to take it on?

AEDL got involved with Mayo Hospital in 2013 when I learnt that the century–old Newton Hall was to be demolished for road widening. At that time my father Iqbal Z. Ahmed was a trustee of the hospital and was engaged in raising funds for and making improvements in the institution.

As Mayo is both an unprotected heritage site and the busiest hospital in the Punjab it was a two-fold chance to assist in its enhancement as well as a chance to carry on with my father’s work there.

Back then we were able to save Newton Hall, map out the entire 50 acre site and survey its circulation flows in an effort to prevent the slated demolition and propose further improvements. Our efforts to save the building succeeded but the hospital did not commission the other proposals.

Four years later in 2017, Nayyar Ali Dada asked me to share the office’s work with a newly formed NGO called Friends of Mayo Hospital (FOMH) of which he was a board member. It was through this NGO that AEDL was able to execute its first project at Mayo.

What areas of the Mayo Hospital have been rehabilitated, restored and renovated by you and your team?

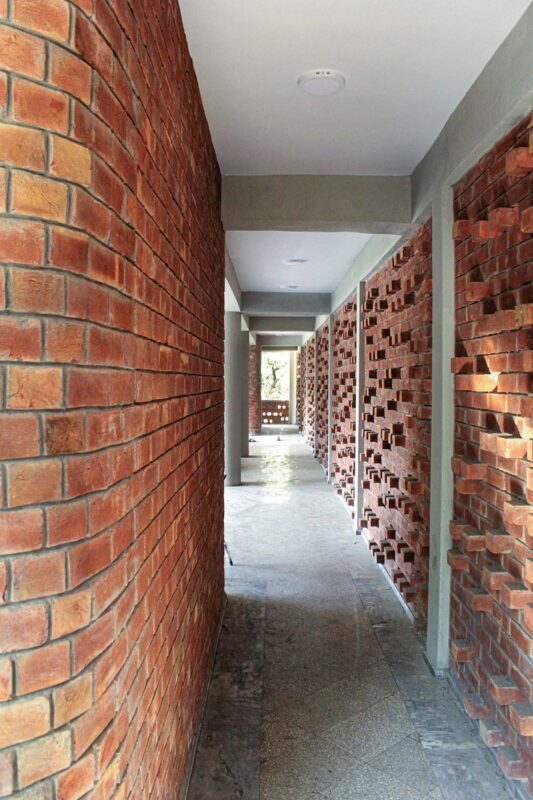

We have worked on two spaces in the 19th century main building, known as the ghari ward – starting with the reception hall, then the east medical ward and its veranda.

Our strategy to rehabilitate the spaces was to find a functional balance between historic building features and different interventions made over time. The design interventions were executed with sensitivity to materials used in the heritage structure but at the same time we infused them with modern elements. Ease of use, and hygiene were the primary motivations behind the design.

We also played up the aesthetics of the historic structure that we had found in a dilapidated condition having suffered the blows of time. It gives us great pride when we say that our work is now considered the benchmark for all future works in the Ghari ward to be done by FOMH.

On paper we have also prepared detailed renovation drawings for the cancer ward, ENT ward, proposed three new parking structures as well as a new ambulatory corridor and ambulance bay, a police chowki (checkpost) as well as canteens, public courtyards and more musafir khanas (visitors’ pavilion).

Mayo Hospital was built in the late 19th century (1871) during the British Raj. What sensibilities had to be kept in mind when conserving a heritage space such as this, in terms of design license and construction material?

The primary design impulse while working on this building was to retain its Neo-Romanesque character while also upgrading its performance and making it compatible with current needs and use.

Since the building has been stripped of its original character, we were careful not to introduce any element that would alter its personality further but rather allude to its past grandeur in a simple, sophisticated way. This objective was critical in our view even when introducing new elements such as oxygen and nitrogen pipes that they neither interfere with the building’s lines nor disrupt its aesthetics.

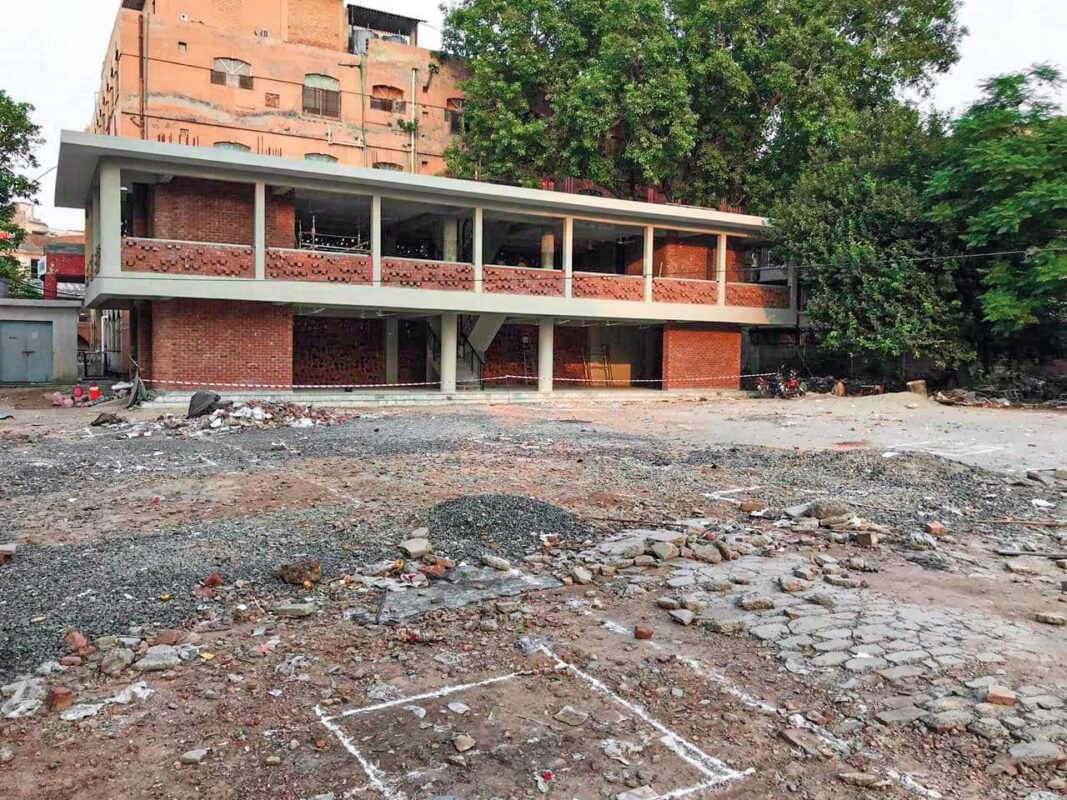

Please tell us about the newly constructed Visitors’ Pavilion (musafir khana). Its been noticed that sustainability plays a vital role in your informed choices as an architect- open space design/ ample sunlight/ cross ventilation via brick latticework/ water recharge/ green cover via plantation of indigenous trees. How much of your architectural language is influenced by climatic performance and regional design?

Pakistan is an energy strapped country, and Lahore is fast becoming a water scarce city.

In light of this developing reality, new buildings must shed habits from times of plenty and reassess their place in the greater scheme of things.

At AEDL, the buildings we make are informed by this reality as well as local responses to climate and culture. However, what we categorise as local is not bound by a specific time. In our view a Mughal building is as significant as a colonial nursing hostel or a modern building that uses local building materials and climate response to generate design.

There are lessons to be drawn from all architectures be they Raj period buildings or modernist villas built in earlier decades after the creation of Pakistan. The new musafir khana we designed at Mayo absorbs lessons from the past but weaves them into a new narrative of climatic adaptability and energy scarcity.

By using red brick jali (lattice) on one side of the building and leaving the other side open, we’ve succeeded in creating a constant air flow through the building. This very simple gesture is an applied lesson from both Mughal and Raj period architecture.

We also reclaimed a plot measuring over 3000 square yards, previously an unutilized dust patch, by turning it into a public courtyard where the design allows surface rain water to drain into open patches of permeable ground, thus enabling ground water recharge. The courtyard has also been planted with native deciduous trees for shade in the summer and sun in the winter.

What has been the most challenging aspect of working on a government project like this?

As always with proposals that challenge existing norms, the biggest hurdle is to convince people of the merits of a new thought.

When we first presented the musafir khana design to then-Health Secretary Punjab two years ago. The secretary told us point blank that our proposal was third rate and that the he would want us to add air conditioners, aluminium windows, leatherite sofas etc. So it is often this disconnect between appropriate and aspirational architecture that we find hardest to address.

You have received much acclaim and won many accolades for your work on the Mayo Hospital. Please share some of the honorable mentions and awards you have received as an acclamation of your trans-disciplinary work on this project.

We were included in the Architectural Digest AD100 list for 2018, as one of the hundred best practices in South Asia. We received gold at the International Design Awards in Los Angeles for a chandelier designed for the hospital called the Newton Light. We also received nods from The London International Creative Competition in London, the Architecture Master Prize in Bilbao and with God’s grace look forward to garnering further accolades for the country for FOMH and the office with future projects already planned for the hospital.

With a degree in architecture from NCA, Lahore to a masters’ degree in Urban Planning from Columbia University, New York City, which alma mater has defined your design language the most and why?

I received my architecture degree from the NCA and did urban design at Columbia. Both programmes taught me very different things but it was the NCA that defined my outlook and design language.

At the NCA, I learnt the value and complexity of vernacular architecture and that appropriate design solutions do not necessarily have to come from academic training.

Columbia taught me the value of thinking on multiple scales at the same time and to view the city as a constellation shaped by vested interests and stakeholders.

Both these insights enabled me to see buildings and the city they sit in as connected and shaped by the people who inhabit them.

What inspires you – artistically and creatively? Any particular era/culture/ place/ object/ element that informs your creative sense the most?

I don’t have a specific bias towards any era, culture, place or object. In my view every object and each place has the potential to impart knowledge if one keeps an open mind.

The only thing I don’t like is poorly-proportioned or placeless architecture and planning that is unsympathetic to the people who use it.

At the same time, what inspires me most are original and creative solutions to existing limitations and ongoing problems.

What role has your hometown, Lahore played in shaping your design aesthetic?

Lahore is a city that looms large on my imagination. It’s the city I grew up in and learnt to explore on late night drives when all is quiet and moodily lit. Before the interventions that changed it from a city of gardens into a city of concrete, Lahore’s historic neighbourhoods were places where one could glean the symbiosis between user and building.

Twenty years ago, the city was a place where one could casually stumble upon an object of outstanding architectural value. Sadly the city has lost much of its charm and while it’s understood that cities change over time, this change should not have come at the cost of the city’s incredible stock of historic buildings.

Having said that, Lahore is not a lost cause and what inspires is the fact that we can still save it. I believe we can still invigorate the city with buildings that are not only beautiful but also reflective of the city’s once unique character.