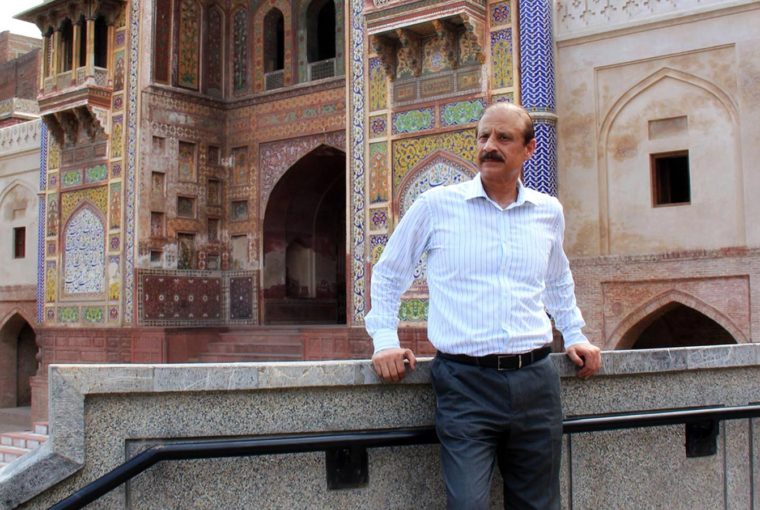

Kamran Lashari, Director General of the Walled City of Lahore Authority, is a man on a mission, tasked with preserving some of Lahore’s most iconic heritage sites enclosed within the ancient heart of the city.

The Walled City of Lahore, once the seat of the Moghul Empire, was protected zealously by its rulers, who enclosed it within a formidable wall and 13 impenetrable gates. Through the ages, as the rule of the Mughals gave way to the reign of the Sikhs, colonization by the British and eventually to present day Lahore, the gates were thrown open, many destroyed and the sanctity of some of the region’s most ancient heritage sites and cultural monuments lay unguarded.

Hence, the setting up of the Walled City of Lahore Authority (WCLA) by the Punjab Government in 2012 was hailed as a much-needed step. The body was given only one mandate – the conservation, protection and maintenance of the Walled City – and the authority to do it autonomously, without getting caught up in governmental red-tape.

The organization is faced with a behemoth task, but the man chosen to head it would have it no other way. Kamran Lashari, Director General of the WCLA, is a civil servant with an illustrious career that has included prestigious positions such as Deputy Commissioner of Lahore, Director General of the Parks & Horticulture Authority, and Chief Commissioner of Islamabad. Known for his passion for the arts and heritage, he is no stranger to taking on public service projects that are enormous in their scope and vision. He is after all responsible for giving Lahore its first food street back in the day when the concept of a pedestrian-only zone in the congested heart of the city seemed like an impossible dream.

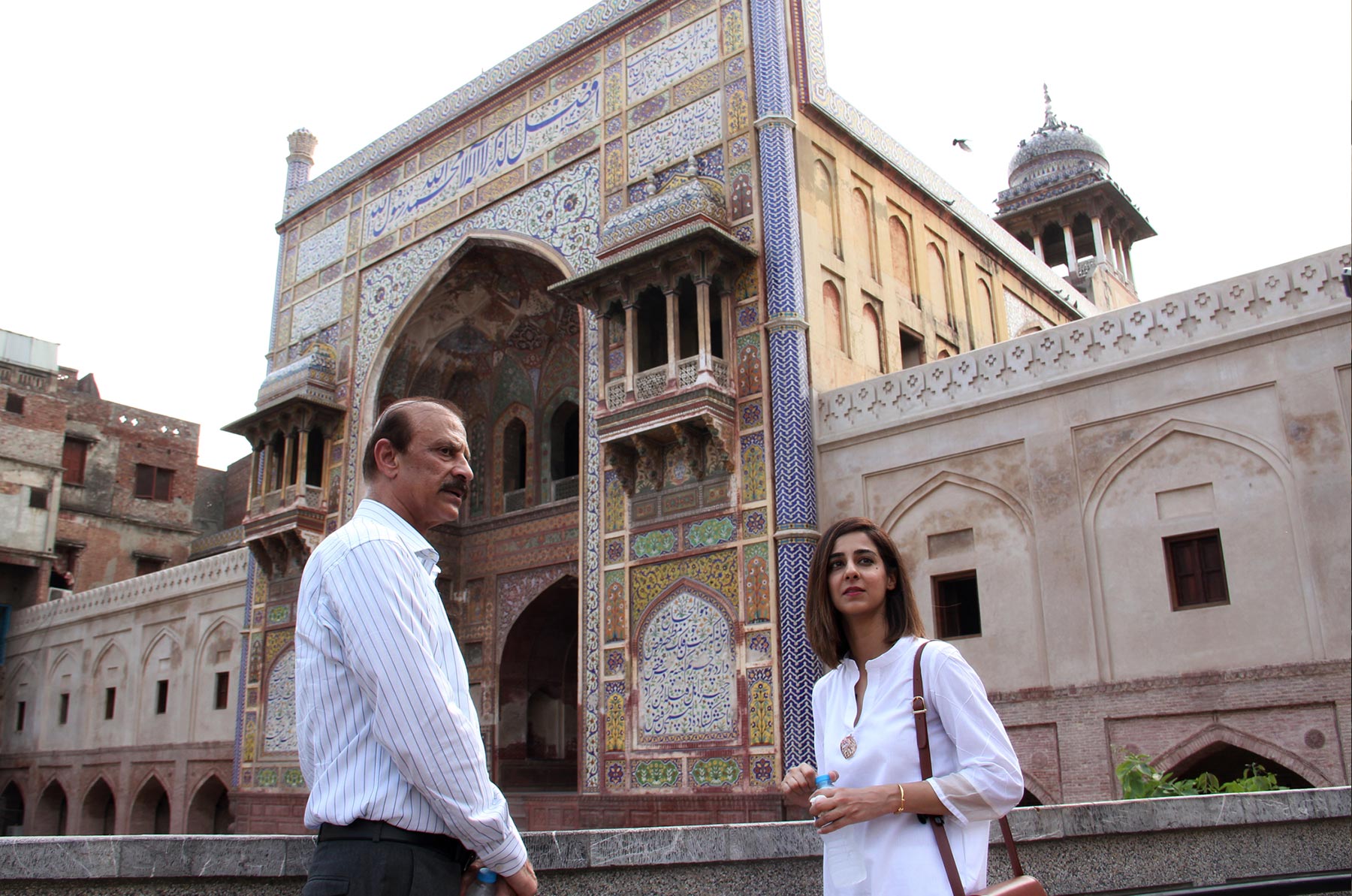

In an exclusive conversation with DESTINATIONS, he sheds light on the WCLA’s expansive plan for the conservation of the Walled City, which not only includes restoring old buildings but also giving the clogged network of streets, shops and residences a much-needed infrastructural uplift.

The restoration of the Shahi Hammam has garnered international acclaim by winning the UNESCO Award of Merit for Cultural Heritage Conservation. However, the hammam was but one important section of a wider restoration process. Can you take us through the entire project and its process of evolution?

The WCLA launched the Royal Trail Restoration Project in 2012. The Royal Trail is a passage inside the Walled City leading from Delhi Gate to Masti Gate. It was the route used by the Mughals while travelling from Delhi to Lahore and going up to the Lahore Fort. As a pilot project, the first phase of restorations focused on the area between Delhi Gate and Chowk Kotwali and the work was completed in 2015.

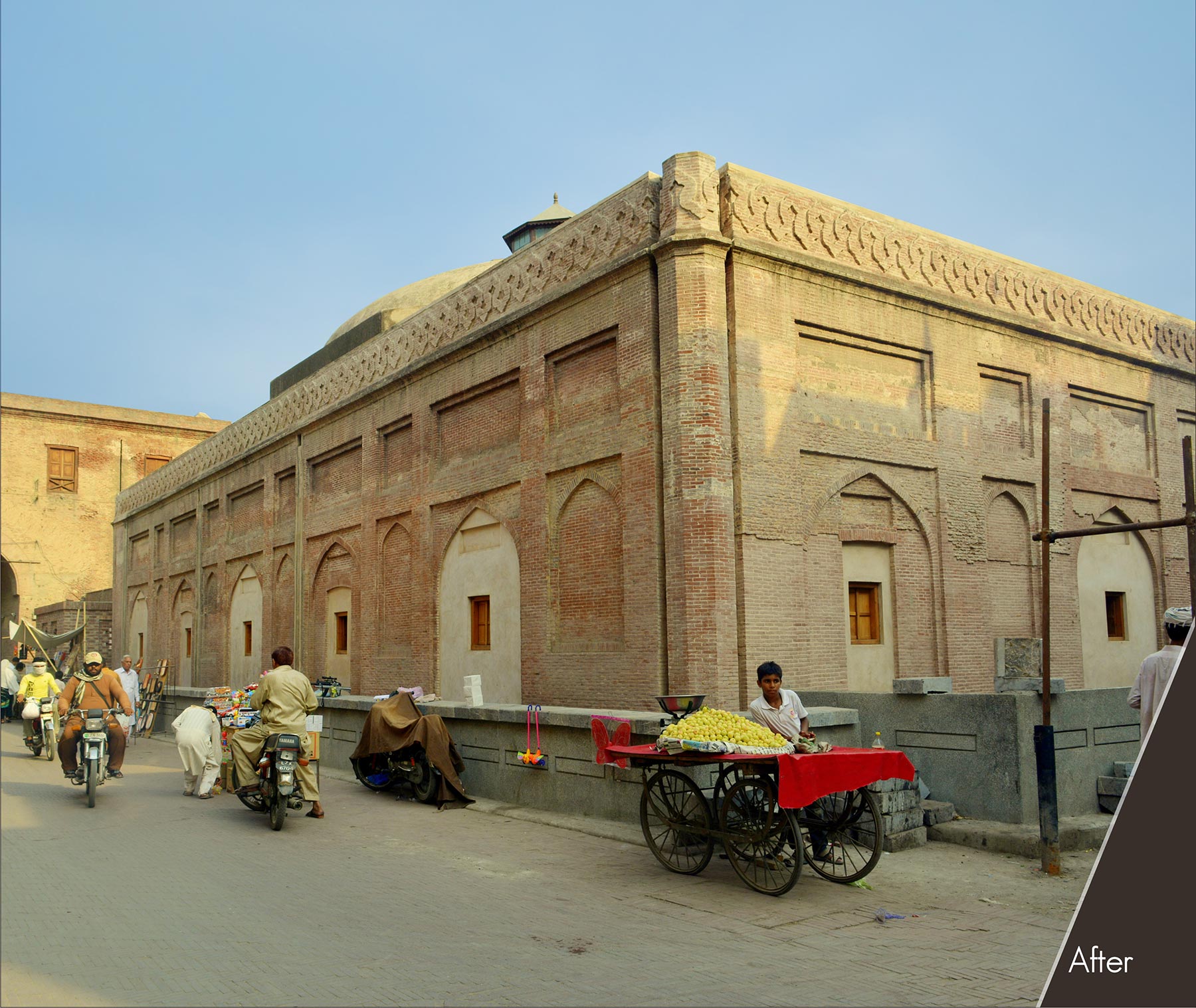

This section of the Royal Trail included two main monuments – the Shahi Hammam and Wazir Khan Mosque. Encroachments were removed from both these sites, which was one of the hardest parts of the entire process. Over the years,

shops had sprung up outside both places; in fact, you could hardly see the face of the hammam due to the shops encroaching on it. The WCLA achieved this uphill task with the collaboration and support of the community. Our social mobilization teams held several awareness and negotiation sessions in this regard.

The conservation of the hammam’s interior was carried out by the WCLA in partnership with the Aga Khan Trust for Culture. The funding for this project was provided by the Royal Norwegian Embassy. During 1991, the archaeology department had covered up the ancient hypocaust system by laying down marble floors in all the rooms. These floors were excavated and the building’s ancient foundations were revealed, exposing the original waterworks and re-establishing this monument as a historical bathhouse and heritage site for the world to marvel at.

On 1st September 2016, we received news that the project had been awarded the Award of Merit in 2016’s UNESCO Asia-Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation held in Bangkok.

How has the restoration of the Shahi Hammam benefitted the Walled City as a whole?

I think this project is one of its kind in the Walled City. Imagine a building hidden by encroachments, with there being very little knowledge about its importance as a heritage site, suddenly being revealed in all its glory. Tourists have started coming in and the local community has benefitted economically. Local boys and girls have been hired as tourist guides and trained as curators of the hammam. Moreover, I feel that the Walled City is receiving attention from all corners of the world since the successful completion of this project. In fact, famed writer and historian William Dalrymple recently tweeted about the site, calling it “the best new architectural restoration project I’ve seen anywhere in South Asia.”

How challenging has it been to find craftsmen with the necessary skills to restore ancient monuments to their former grandeur?

It has not been an easy task but thanks to the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, which has experience of such projects, we were able to put together a team of skilled craftsmen. For the restoration of the hammam’s ancient fresco artwork, fresco experts were called in from Sri Lanka and they toiled with the students of the National College of Arts. This was a wonderful training exercise for our own resource in fresco. It is important that the local labour was provided a chance to learn and gain knowledge from skilled international artisans, allowing us to build a pool of local talent for future conservation projects.

What monuments and heritage sites is the WCLA working on next?

We are currently working on the conservation of the world’s largest picture wall here at the Lahore Fort, again with technical assistance from the Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

A second project inside the Lahore Fort is the conservation of the Royal Kitchen, which will be completed by October this year.

This was the kitchen used in Shah Jahan’s time and had been turned into a no-go area. We’re re-opening it as a night restaurant for tourists so they can enjoy royal recipes in a heritage setting.

My conservation team is also working to conserve the two main mosques of the Walled City, the Wazir Khan Mosque and Mariam Zamani Mosque. The conservation of Wazir Khan Chowk as well as the mosque’s northern wall and its façade has already been completed. We will soon be opening up this chowk (square) and have planned numerous cultural activities here.

The conservation of Lohari gate is almost complete and other existing gates are next on the agenda. The very important trails of Bhaati and Taxali Gates are now being documented and you will soon see a marked change in these areas.

What are the major hurdles facing the organization in the restoration works within the androon shehr, some of which may be decorative but a lot of which involve major infrastructural changes? In such a densely populated area, carrying out development works can be no easy task.

The Royal Trail project was designed to improve the living conditions of the residents of the Walled City, as we believe that people living around heritage sites are equally important. It includes not only cosmetic work on building façades but major infrastructure improvements, such as taking the electricity system underground, separation of sewerage and storm water pipes, better provision of sui gas and telecommunication services.

Absolutely, this was not an easy task and a lot still needs to be done. We have been able to restore just 4% of the Walled City and we have huge targets ahead. We have to work in congested streets and during any infrastructure or façade improvement works, we try our best to ensure that business continues unhampered. That is why the project is time consuming.

What are some of the Walled City’s best-kept secrets?

I think a lot remains undiscovered inside the Walled City yet. Every day, we explore something new. The area is unique in its own way, a cultural hub of an ancient empire that has managed to survive in its original state. You can find havelis that are hundreds of years old, and mosques that date back to the Lodhi period and Mughal era. Then there are some of Asia’s largest markets here: Akbari Mandi, from where the East India Company originated with the trade of spices; and Azam and Pakistan Cloth Markets. I can say that every nook and corner has a story. Scholars, sportsmen, writers, singers, artists and poets have been born here.

Dr. Muhammad Allama Iqbal was a resident of Bhaati Gate. Similarly Ustad Daman, Shah Hussain, Noor Jahan, Mehdi Hassan, Shahid Kardar, Gama Pehalwan, Rafi, Maulana Rohi and many others belonged to this city of wonders within a city.

As a civil servant, many of your projects, such as the Gawalmandi Food Street and now the Royal Trail, have involved giving a new face to the city of Lahore and uplifting it. Is there perhaps a personal motivation behind the undertaking of such projects?

I think it’s my personal passion. Nothing creative or different can be done without passion and love for it. Anything that makes people happy motivates me. The Gawalmandi Food Street was a culmination of my desire to bring joy and happiness to the masses.

What are your fondest memories of growing up in Lahore?

Riding a bike to St. Anthony’s school every day. Cycling on Temple Road and staring up at the huge exotic billboards of Regal Cinema. Going to the King Edward Medical College swimming pool in the summer and swimming for hours. These are the memories that I cherish – of a city that was peaceful, where children had freedom to move around. We played on the streets with abandon and cycled wherever we wanted. I also remember the enthusiasm with which we celebrated Eid and Eid Milad-Un-Nabi. I feel that is missing from the lives of today’s children.

Does travel inspire you?

Travelling is my greatest passion and I have seen more than sixty countries. I think I have learned less from academics and more through travelling.

What is your favourite city in the world?

Venice. I am mesmerized by its history and setting amidst a water body of many winding canals. Its heritage has been preserved wonderfully and presented to the world. It’s a dream city.

Through the duration of your illustrious career and the various public administration projects that you have undertaken, is there a particular one that stands out?

My fondest memories are attached with the Gawalmandi Food Street project. It was a new concept back then in the country to pedestrianize a thoroughfare and establish sitting spots by the roadside. It became a place where all social classes merged as one family, one people. It not only uplifted the standards of living of the local community in Gawalmandi but also became a major tourist attraction as a place to enjoy traditional Lahori food amidst illuminated heritage buildings.