With a diverse programme featuring book launches, sessions on topics ranging from politics, international relations, art and education, dramatic performances and dance recitals, KLF gave the city by the sea a weekend to remember.

It was a lovely spring afternoon, the perfect weather for an outdoor setting. The water in the distance glistened bright under the warm February sun. Flowers and foliage were in full bloom and Karachi thronged in attendance. Against the quaint backdrop and old-world charm of the Beach Luxury Hotel, the stage had been set for the opening of the ninth edition of the Karachi Literature Festival.

“Bringing together international and Pakistani writers to promote reading and showcase writing at its best” – KLF had something on offer for everyone. With a cross-generational mix of 281 speakers in attendance and sessions in a number of languages spread over 3 days, the 9th Karachi Literature Festival brought together stalwarts Shahryar Khan, Richard Heller, Aurelie Salvaire and Isambard Wilkinson among a host of others, as well as the likes of Kamila Shamsie, Nadeem Farooq Paracha, Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, all of whom enthralled audiences with their wit, wisdom and plethora of anecdotes.

The departure of winter also seemed to bring with it a very welcome and much awaited thaw of sorts in the icy diplomatic ties between India and Pakistan. A multitude of speakers from across the border including Mani Shankar Aiyar, Sheela Reddy, Saif Mahmood and Aanchal Malhotra among a host of others graced the occasion as did the newly appointed Indian envoy, High Commissioner Ajay Bisaria with his team.

Welcome addresses by the organizers were followed by the distribution of accolades for literary excellence. The Pepsi Best Non-Fiction Book Prize was conferred upon Rasul Bakhsh Rais for “Imagining Pakistan.” Rais also bagged the German Peace Prize along with Ijaz Hussain’s “Indus Waters Treaty: Political and Legal Dimensions” and Akhtar Baloch for “Prison Narratives.”

Winning 2018’s Getz Pharma Best Fiction Book Prize for his book “The Party Worker”, ace cop Omar Shahid Hamid made it two in a row. In 2017, Omar received the same award for his book “A Spinner’s Tale.” Infaq Foundation’s Urdu Literature Prize was awarded to to Altaf Fatima for “Deed wa Deed.”

And as the sun set on the opening ceremony, following keynote addresses by Francis Robinson and Noor-ul-Huda Shah, a Kathak recital by Shayma Sayid served as a poetic prelude to the festival’s opening panel discussions – five interactive sessions that aptly wrapped up the inaugural evening.

Just hours before the fest closed, news of lawyer and rights activist extraordinaire Asma Jahangir’s sudden and sad demise broke. The cheer in the air was replaced by heavy hearts all around. The afternoon and evening’s programme was revised to include a reference for Asma Jahangir jointly addressed by some of her closest friends – I.A. Rehman, Kishwar Naheed and Anis Haroon.

Whatever one’s take on the KLF may be, there is unanimous acknowledgement that in a country like Pakistan, such literary outings provide much-needed alternative forums for discussion and discourse. This year’s edition clearly wasn’t any different.

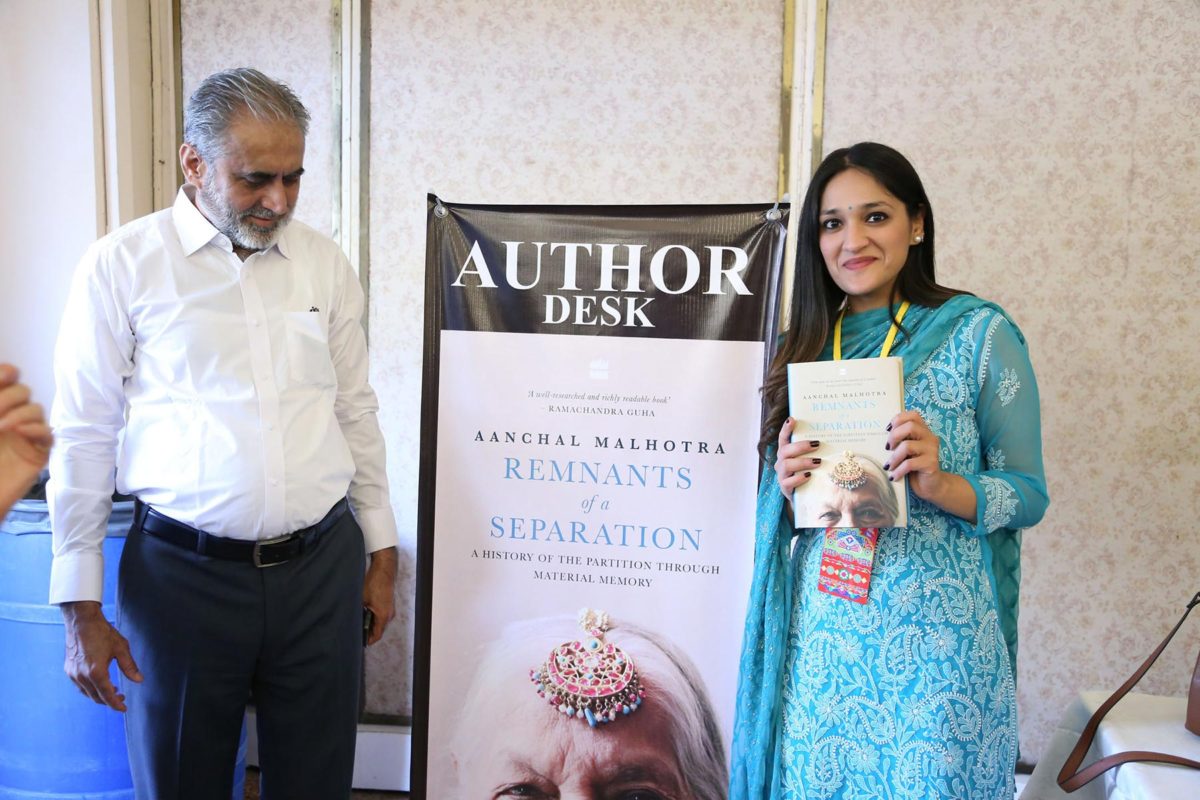

AANCHAL MALHOTRA

ARTIST AND ORAL HISTORIAN

Day Two of KLF and a weekend to boot; the sprawling expanse of the Beach Luxury Hotel was packed to maximum capacity. Just past noon, I was in conversation with another writer when I was introduced to Delhi-based Aanchal Malhotra. Clad in a turquoise chikenkari three-piece and depending on which side of the border she had purchased them, a pair of gold mojris or khussas as they are more popularly known in our neck of the woods. Aanchal’s book, “Remnants of a Separation: A History of Partition Through Material Memory” had just been launched to a packed house and a captive audience.

Artist and oral historian turned author, Aanchal is the co-founder of the Museum of Material Memory, a digital repository tracing family histories of the Indian subcontinent and social ethnography through heirlooms, collectibles and objects of antiquity.

Away from the madding crowds, in the shaded calm of the authors’ lounge, over a fruit and cheese skewer and a much-needed cup of strong tea, Aanchal spoke candidly about her book and her debut as an author. The chronicles are, she explained, “basically about material artefacts that refugees carried across the border with them on both sides – belongings that people chose to take with them when they migrated at the time of partition. My research started with my family, but it very quickly became about lots of people that I did not know. My book looks at partition, yes, that is the main theme, but through the object it also tries to look at the landscape of undivided India, what daily life was like, what things did people use, what languages people spoke, how they made food, what interpersonal relations there were between communities.” The list is endless.

All four of Aanchal’s grandparents find their roots in Pakistan. Her paternal grandfather hails from Malakwal in District Mandi Bahauddin, while her paternal grandmother belongs to Muryali in Dera Ismail Khan. Both of Aanchal’s maternal grandparents are from Lahore. She elaborates: “I think of all the people in the book, my grandparents were the hardest to speak to. There is a certain silence that has developed around the memory of partition – people who’ve lived through it don’t necessarily want to talk about it.”

During partition, people “didn’t have the luxury of time to actually scrutinize what had happened to them – they just had to move on. Because one day you were at home, the next day you were across the border and then you were in a camp and you just had to live life and sustain yourself,” says Aanchal.

And what could be harder than dissecting the emotional baggage of partition with your near and dear. “Talking to strangers can be worked around, but when you know someone so closely and suddenly become acquainted with their history, things change. Understanding and perceptions become different and you start to make sense of why certain mannerisms have developed the way they have. My paternal grandfather Balraj Bahri Malhotra came to India with virtually no money. Our family really struggled – they lived in at a tent at Kingsway Camp in Delhi for many years. So, the frugality with which my grandfather lived life even when he had a lot of money and had built a huge empire made sense,” she explains.

Aanchal’s family owns the age-old Delhi institution – Bahrisons Booksellers, a name synonymous with quality for decades. Today, Aanchal’s “Remnants of a Separation: A History of Partition Through Material Memory” has also made it to one of the many shelves of the bookstore her grandfather opened in 1953. “It’s strange, because we’ve been selling books for 65 years now and it is the first time someone from the family has written something. But I think it’s also difficult because you need to take a step back from yourself to look at why the history of your family, though painful, is regarded as one of India’s most popular stories for post-partition entrepreneurship. While studying my own family, many things came out and this was one of them – it is great we own this wonderful business, have educated many, many minds and lives throughout the years but there are many things that this business is trying to suppress. My grandfather never wanted to look behind, he always looked ahead,” she explains.

It was research for her book that first bought Aanchal to Pakistan in 2014. “I felt kind of stupid for thinking that Pakistan would be any different to India. When I arrived here, that stupidity really dawned on me. How was it possible that I have never been to Pakistan yet I could slip into society so easily? You know people tell me, “aap Lahore main hain – welcome to Lahore” and I instinctively say “Lahore to mera bhi shehr hai”. That is because I can understand it, because I’ve heard so many stories of a time when it was undivided and people have wonderful, wonderful memories”.

Aanchal, here’s to the countless remembrances of an era bygone shaping many a new friendship!

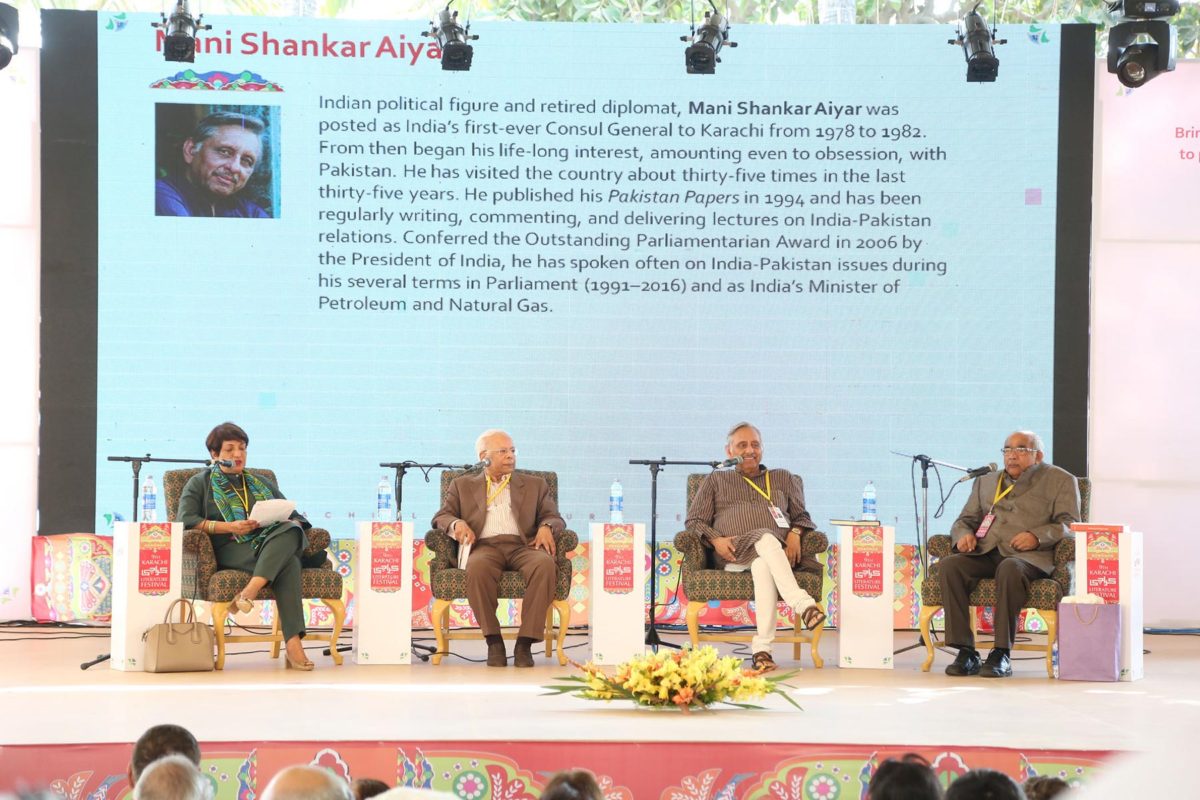

MANI SHANKAR

FORMER DIPLOMAT/POLITICIAN

It was the afternoon of Sunday the 11th of February. The atmosphere was sombre – very, very sombre. The news of Asma Jahangir’s passing had just broken and Mani Shankar Aiyar wasn’t keen on doing interviews.

He reminisced with a heavy heart: “Apart from being a great Pakistani voice, she was also a great friend of mine and so I feel very, very saddened that she’s no more with us. But the kind of direction she gave and the goals she set, remain after her. The highest tribute we could pay to her is to continue working towards those goals. And once we reach the manzil, then maybe we can jointly built a monument to her on what was once a hostile India-Pakistan border and became a friendly border because governments started listening to the enlightened voice of Asma Jahangir.”

Lahore-born former diplomat turned politician Mani Shankar Aiyar served as India’s first-ever Deputy High Commissioner to Karachi between 1978 and 1982, a city where he spent “three glorious years” and has also remained a regular visitor to over the decades. In fact, Sana, the youngest of his three daughters was also born here.

In strained times such as these, Aiyar feels people-to-people interaction, of which he has been a vocal advocate, is the only way ahead. He elaborates: “My very presence here shows that I am delighted to avail of such opportunities. And the kind of welcome I received here, I am astonished at. Yes, I know hundreds of Pakistanis but these are thousands who are welcoming me with great affection and great love and therefore I would like to invited again and again to participate in such festivals.”

As a professional diplomat, Mani Shankar Aiyar recognizes that “all this is very marginal to the interstate relationship and for the interstate relationship to move forward.” He elaborates: “I believe that the Shimla Agreement, the agreement that came about in January 2004 and the movement that was made forward in dramatic manner, even on an issue like Kashmir, between President Musharraf and Dr. Manmohan Singh and their envoys, indicate that if only we can start a process of uninterrupted and uninterruptable dialogue, we may far quicker than we realize arrive at solutions that are constructive, acceptable to both sides and in accord with the historical record”

“Pakistanis who suddenly became Pakistanis from being Indians on the 14th of August 1947, had a tendency to define themselves negatively, as being Pakistanis because they are not Indians. The younger generation has no need whatsoever to do that; they are Pakistanis because they were born in Pakistan and any question of them being Indian has never arisen.

This means a huge change in mind-set. Unfortunately, it is also associated with indifference towards India, whereas the previous generation was very involved with India. We could turn around this indifference to the advantage of both countries, if it were to become part of a mind-set of saying, “I am confidently a Pakistani and therefore I can confidently deal on a sovereign basis with India.” That is the big hope in my heart,” he adds.

Till then – “You have to wait; there is no alternative. The Government of India has decided to put a padlock on people-to-people relations. The visa regime now in operation is an example of this kind of an attitude”.

Cynicism aside, Aiyar does see light at the end of this dark tunnel. “I have met with a lot young Pakistani people today whereas all my earlier friends were all from an older generation. They had great affection for me which is why I am welcomed so enthusiastically in your city. But I see from the youngsters who have met me, talked to me, taken selfies with me, asked for my signature that there is also a desire to end the confrontation and come to a reasonable relationship and a sensible Indian government would leverage that to its advantage.”

Fingers crossed, Mr. Aiyar – here’s to a less hostile neighbourhood, one day.