A visit to a small, secluded and charming fishing village in Balochistan, bordering the coast of Karachi, revealed that it has changed over the years but there’s still a little magic left.

It was in the middle of the afternoon and we were stuck somewhere in the boonies on a singular road that went through a rocky mountainous range between Karachi’s popular picnic beaches and the bareness that we knew to be Balochistan. Most of us didn’t have a clue exactly where we were, or how far from ‘civilization.’ On call for the music video Shahi Hasan (of Vital Signs fame) had been filming since 3am, hungry and sleep-deprived, I had stopped enjoying the ‘experience’ a while back and was desperately scanning the horizon for any sign of deliverance from this awful heat.

I spotted what looked like water. I couldn’t believe it. “So, where should we go?” asked Shahi, finally ready to take a break. “Over there,” I responded, pointing to a teeny tiny strip of the sea in the distance. Where there was water, there were bound to be people.

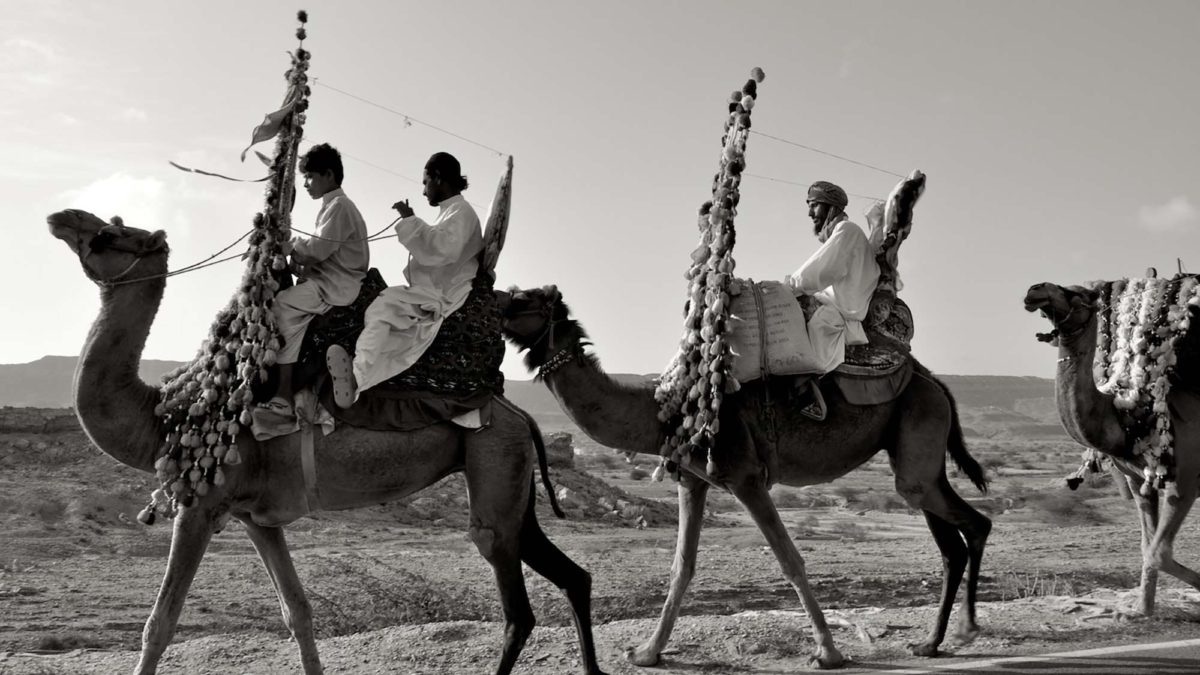

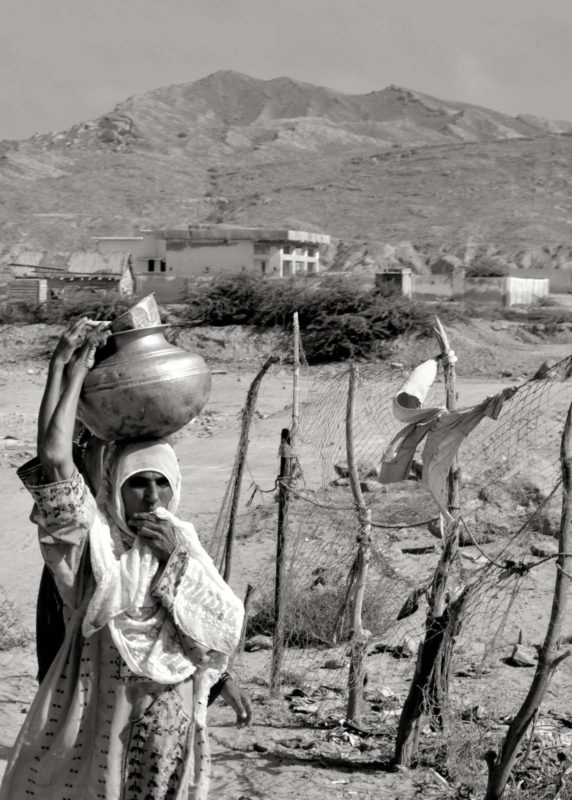

As we got closer, three men riding camels at a brisk jog passed by. Their saddles were quite colourful — a complete contrast against the brown environment — and displayed cutwork in mirrors that reflected the sunlight so you could see them approaching from a distance. They seemed very amused by our presence. A little forward and we saw a lone man who had let his camel out to graze on whatever little patch of grass was out there. He too seemed quite pleased at having company for a few minutes. We even crossed a small group of women who had metal pails balanced precariously on their foreheads as they went about collecting drinking water for their homes.

The children ran up to our bus before we could even get off. The fishing village we had arrived at did not have any concrete houses; there were only shacks. The only things that seemed to carry the slightest value were the pots, pans and pails piled outside what I assume was the kitchen. The only cover on the beach were little huts made from planks of wood roughly nailed together with large gaps between each plank. Holding it together was a fishing net. This was to be our shelter. A sign above the only, incredibly modest, store read ‘Welcome to Mubarak Village.’

“Do you have any food here?” one of the crew members asked a local. “There are no shops you can buy it from, but I can make you some,” he responded. “For 20 people?” the crewmember asked. “Yes, but I must warn you, it will be very expensive,” the local said. “How much?” the crewmember inquired. “500 rupees and not a paisa less,” responded the local firmly. “We’ll give you 2,000 rupees,” said the crewmember, “Just feed us well. Please.” The naiveté of the local was endearing. And indicative of how completely cut off this charming little village was from the outside world.

Our lunch was a feast of rice, lentils and potatoes cooked in earthenware pots over a wooden fire lending it a smoky flavor and it was absolutely delicious. While the others napped, I decided to go out and explore.

The sea was so beautiful. Before Mubarak Village, I hadn’t seen such a beautiful beach in Pakistan before. The water went from emerald green, to dark blue with depth. Closer to the shore, in the pools accumulated between the rocks, it was completely transparent. You could see tiny little sea creatures swimming about. Some children dove into the sea with short planks of wood fashioned like tiny surfboards trying to ride the waves – but the waves weren’t big enough.

I was raised with a healthy fear of going in too deep to prevent accidental drowning – even though I can swim – so to see children engage with the sea so fearlessly was refreshing. Some of the fishermen were setting out to sea and their poor boats in contrast with the emerald green sea were also visible. I tried to climb a few rocks leading up to a cliff to get a better view of where we were and was constantly followed by a gang of children – ranging from eight or nine years old to as young as one of them holding a baby in her arms.

While I struggled with trying not to slip and fall, the children hopped up the cliff as if it was nothing at all. The little girl with the baby alarmed me most of all – the climb was precarious, the drop far down and lethal. But they were so confident, at ease and so much at home. Their agility put me completely to shame.

Mubarak Village and its wonderful people had completely stolen my heart and I was going to come back. Definitely.

Fast forward a few years later. I am bundled in my car with all of my camping gear, a German friend who had recently moved to Karachi and two other friends in another car in tow. We’re off to camp on the most beautiful beach in Pakistan and it was going to be wonderful. By now, roads had been developed, awareness had increased and everybody who ventured to Balochistan knew where Mubarak village was. I had cycled the entire route from Karachi to Sonera Beach – next to Mubarak Village – a few times before and was quite confident I could get all of us to our destination.

Crossing the necessary check posts and after getting lost a couple of times we finally made it. The village had changed – it had grown bigger. Instead of one or two beach shacks, there were about 20 and as is inevitable with any place that experiences even the slightest boost in tourism: there was trash on the once pristine beach. But we had been driving for hours and were not going to turn back.

We befriended one of the locals, who promised to stay with us. Apparently, the villagers are a bit suspicious of ‘outsiders’ spending the night and may have asked us to leave, something we really didn’t want to do. We set out in search of the ‘right’ camping spot and found a secluded area close to some cliffs on the other side that separated us from Sonera beach.

We set up our camp — pitched our tents, spread our sleeping bags, took out our food, sat on our foldout chairs. Our local friend was given a sleeping bag as well. We stared at the stars, heard the sea and Local Friend told us several stories — one of them involving a container ship at sea that met with an accident resulting in them offloading some of their cargo … which turned out be crates and crates of foreign beer (“It had a red cover”) the villagers enjoyed for some time.

“I don’t know why you guys are so fascinated by the stars,” he said, when I pointed out different constellations. “We see them every day.”

“Every few minutes I see men go between those rocks, what’s going on?” I asked him. “They’re using the toilet,” he responded with a laugh. I think I could’ve done without that piece of information.

Mubarak Village may not be the same small, secluded, charming little fishing village I fell in love with, but the increased tourism had provided the locals with an additional source of income køb viagra. They understood the need for conservation – of their environment – and struggled with implementing measures that would ensure their beaches remain clean. But as with any major change, they are learning to adapt to it and make it work to their advantage.

While the others slept, I kept waking up in the middle of the night and would look out at the sea, afraid the tide might reach us. I stepped out into the dark and saw my German friend attempting some kind of yoga move under the moonlight. We didn’t say a word. The sound of the waves was enough.