Noted journalist and a native of Peshawar, Iftikhar Firdous takes us on an enchanted journey of his beloved ancient hometown through times present and times past. As you trawl through old bazaars and cross historical monuments, you get to soak in the vibe of a city that has been alive for almost 2,500 years now, homing and enabling multi-cultural and multi-lingual communities to converge and coexist in complete peace.

Photography: Mobeen Ansari

It is a city wrapped in nostalgia. The sense of belonging here relates to a past that, while one never witnessed, one can easily conjure up. As you utter the word ‘Peshawar’, before the plosive “P” can reach the rhotic “R”, your eyes roll back into their hammocks and a city begins reconstructing itself. Before you know it, you’ve entered the Asmai Gate, the shimmer of gold in the ornate shops almost too much for the gaze, softened only by the alluring lapis lazuli brought from Badakshan. You won’t stop there for long; with the next step you’re in the year 1892 and the Hastings Memorial is being inaugurated. In a moment, it is renamed Chowk Yadgar, it’s 1965! The clangour of metal utensils from the Raiti Bazaar brings you back to the present. But something adamantly pulls you to return to the times gone by.

You find yourself looking into Karimpura, where the bells of the mandir, Dargah Sri Peer Rattan Nath Ji, are being rung. Traders from the Bazaar-e-Kalan look out of their jharokas (an overhanging enclosed balcony, ornamental in design) to hear the azaan from Masjid Mahabat Khan. It’s all there, even the little-known Rishi Midwifery Hospital established by the Jewish community that once lived in the Muhalla Kheshgi. And while you feel the diversity of the city with closed eyes, you’re almost shaken by its symmetry – the entire edifice of culture and faith folds into the Gor Khatri citadel: Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism and the Raj all packaged like a gift called the Walled City.

You wait to hear more, you think it can be sustained but then a long prelude to silence ends and when your eyes finally open, you are bound to ask, “Where did that Peshawar go?”

Fa Hien, the Chinese travelling monk of the 4th century called it Polusha (Purusha). Three hundred years later, during the Tang dynasty, the historian Hiun Tsang who journeyed to collect scriptures of Indian and Chinese Buddhism through the city, referred to it as PoloshaPulo (Purushapura) while the Mas’udi, Al Beruni, Abul Fazl described it as Parashawur. The present name, Peshawar, is ascribed to Emperor Akbar – which the historian SM Jaffar wrote “means Frontier Town”. It is one of the oldest cities of the world, located at the confluence of Persian and Indian civilizations and has been nurtured by diversity and culture.

Growing up in Peshawar in the 90’s was a medley with bits of Pashto, Hindko, Farsi, Dari and Punjabi. The silent murmurs of the Afghan war in school became violent protests in college. It’s as though the city jumped a quantum of a millennium, literally by the year 2000.

Everything begun crumpling; the ideals of diversity and acceptance faded into historical books. The red bricks of the Mughal architecture were impeded by sand bags, barbed wire and concrete blocks. For more than a decade the city reeked of dynamite and blood. Many left, those who stayed back clung to a thin bark of hope: “There will be good times again.”

And now when the war has subsided amid perishing historical structures in the Walled City of Peshawar, some crumbling monuments stand strong. The iconic architecture may be marred by time yet the residual grandeur remains the city’s pride.

Recognising the worth of rich history, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government plans on fostering the architecture as a tourist attraction. The historical buildings, if restored, along with the lush green valleys of the province, can provide a wholesome experience to tourists and generate revenue for the government.

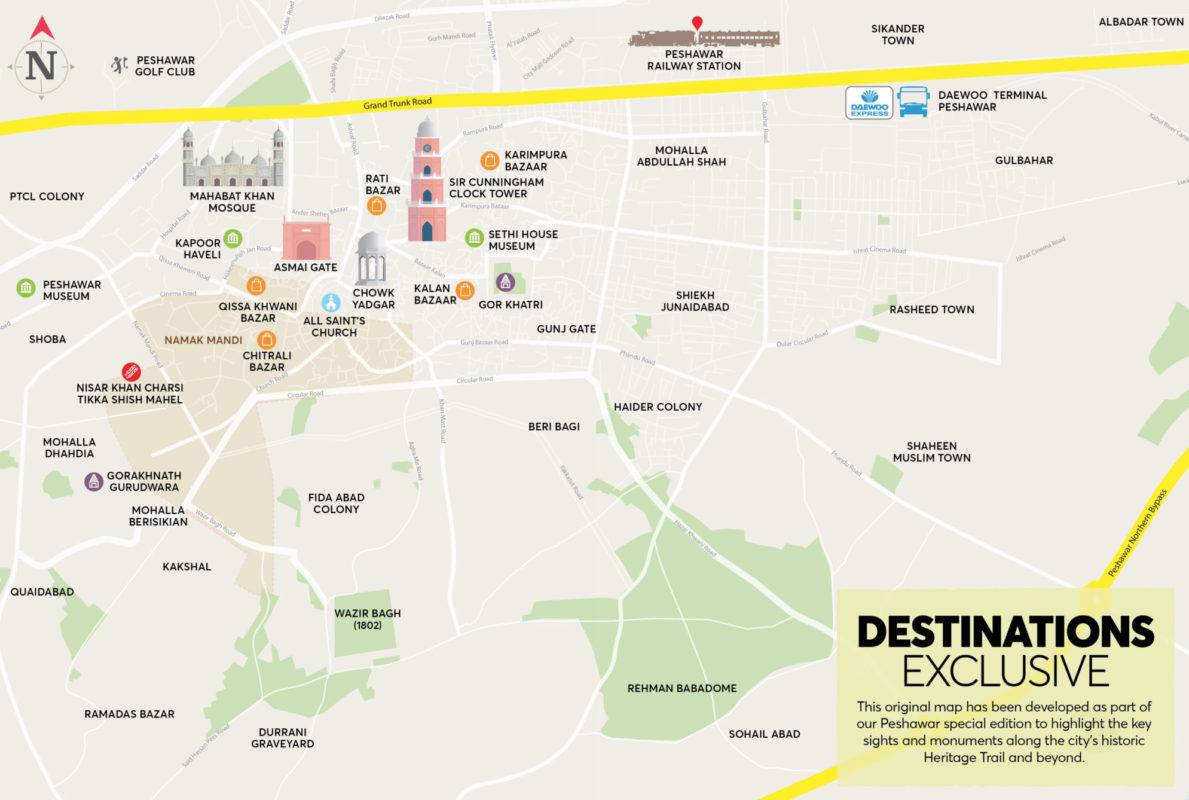

With this thought in mind, the KP Directorate of Archaeology and Museums has set out to build a heritage trail aiming to restore historical sites and adding facilities to make it tourist-friendly. The PKR 300 million worth trail makes its way through a number of landmarks that tell stories of the city’s historical past.

The trail begins at the Cunningham Clock Tower, locally known as Ghanta Ghar. The historical clock tower illustrates history even if it no longer tells the hour. Dating back to the 20th century, the tower was erected on Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee celebrations and named after AFG Cunningham – then commissioner of Peshawar and its surrounding districts. Now home to an illegal fish market, the tower’s foundation is eroding due to the water used to keep seafood fresh.

Although the directorate managed to restore part of the clock tower, unfortunately it could not succeed in moving the fish market elsewhere; its efforts to preserve the richness of this antique beauty marred by a lack of regard for historical conservation.

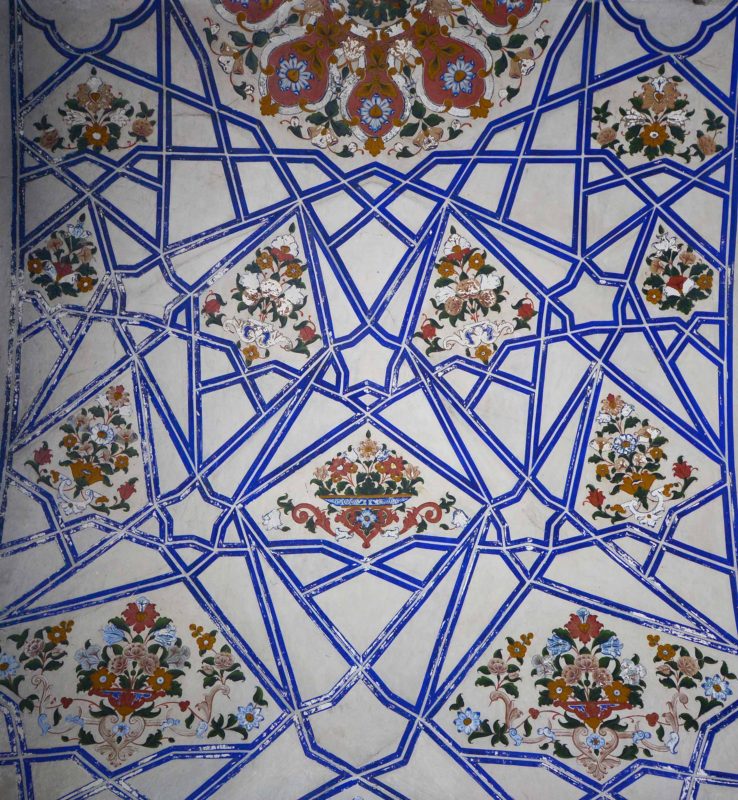

The trail then leads you to Bazaar-e-Kala and the Sethian Mohalla – once an upscale neighbourhood housing seven palatial wooden havelis (mansions) built in 1882 by the Sethis, a trading family who benefitted from international transactions mostly in connection to Central Asia. After the Bolsheviks toppled the Czarist Empire of Russia towards the close of the First World War, the Sethis’ fortune fell (they lost both Central Asian markets and valuable bonds that no longer held value in the face of new age currency). But to this day, the havelis (known as the jewels in Peshawar’s crown) serve as a reminder to their opulent and lavish lifestyles.

In 2006, the archaeology department acquired the rights to one of the havelis and began its conservation process. The haveli is truly a sight to behold; it stands as a testament to mastery over delicate woodwork carved into floral and geometric patterns. The renovated structure was opened to the public in February 2013 and continues to receive local tourists every day.

Moving forward, the trail brings you to Gor Khatri – a caravanserai built over the site of ancient ruins. The complex, partly restored by the KP Government, boasts remnants of history from the 16th through the 20th century.

In the 16th century, Mughal Princess Jahanara Begum built the caravanserai – Sarai Jahanabad – aiming to provide shelter to traders travelling between India and Asia. It housed a mosque, a sauna bath and two wells.

The refurbished Sarai Jahanabad rooms are protected by aluminium gates and rented out to artisans displaying a variety of crafts promoting Pakhtun heritage. The building is also used for exhibitions and local art events.

In the 20th century, the fortified compound was declared Peshawar’s first Governor House when Italian mercenary general Paolo Avitabile – made governor by Ranjeet Singh – adopted it as his residence in 1838. The Italian mercenary general added two tall gates on either sides and rooms on the top floor that boast skyline view of the city as the structure lies at the tallest point of the old city.

Photo by Uzair Aziz

During the Sikh rule, a Lord Shiva temple for Hindus and a gurudwara for the Sikhs were constructed within the compound. The 17th century Guru Gorakhnath Gurudwara and Lord Shiva Temple maintain their original structure with an added wall surrounding them. The temples are open for worship.

The site saw further additions during the British Raj – the most famous is a firehouse built in 1912. The fire brigade exists to date with two vintage fire engines manufactured in 1918 and 1921 by Merryweather and Sons of London respectively. In January 2014, the KP Government, backed by the President of the Vintage and Classic Car Club of Pakistan, Mohsin Ikram, and Karachi-based expert Romano Karim, breathed new life into the engine remnants. The restoration cost almost PKR 25 million.

The government also restored the firehouse in 2016. After three years of conservation work, the building is considered a popular tourist attraction for both locals and foreigners.

Archaeologists have excavated the Gor Khatri complex in attempts to establish an exact historical profile of the city. The artifacts removed from the site are displayed at the city museum within the compound. The four-year-long excavation study, published in the British Journal of Current World Archaeology under the title ‘The deepest and the biggest excavation in the world’, revealed 20 layers of the city ranging from the British to the pre-Indo Greek era. The research found traces of Peshawar as a province in the 4th to 6th century Persian Achaemenid Empire.

Where the trail shows potential for tourism, it has been beleaguered by lack of a working traffic plan and reluctant locals who fear losing control of their beloved history. The heritage trail is definitely a great effort and its significance cannot be undermined, but to say that the diversity of the historical beauty of the city is only limited to the trail is a severe reduction of history and what other architectural wonders the city has to offer.

The Asmai Gate is one the 16 gates that the Walled City of Peshawar once had. The wall around the city, built for its protection by General Avitabile, was 15 feet high and 2 feet thick and its remains can still be seen. Some of the gates have been resurrected as part of the restoration project of the city’s architecture but the majority are now just part of history books.

Once you enter through the Asmai Gate, you find yourself in the Ander Shehr, in the goldsmiths market, a narrow serpentine street with glittering gold everywhere. The Vishnu Bairagi Temple of Asmai, named after Asa Devi whose Asthan was visited by Guru Nanak, the founder of the Sikhism, can be found here. The temple was damaged after it was sold to a merchant from the Khyber tribal district, who wanted to demolish it. However, it is now being reconstructed.

Close to the temple is the Masjid Mahabat Khan, the biggest and the most beautifully built of all Mughal mosques in the city. It was built by Zamana Baig, also known as Mahabat Khan, an officer of the Mughal Emperor Shahjehan. The white marble of the mosque has a cooling effect like no other place and its pool of water has a blue texture to it, much similar to the Badshahi Mosque in Lahore and Delhi’s Jamia Masjid.

Photo by Uzair Aziz

Outside the Ander Shehr was the Hastings Memorial that carried inscriptions in no less than three languages – English, Persian and Pashto, to perpetuate the memory of Colonel EC Hastings who died there December, 1884. It once stood between the Mahabat Khan Mosque and the Cunningham Clock Tower. However, the memorial was taken down to construct an underground parking.

It is from here that you turn towards the Dal Garan Bazaar, where the aroma of green and black tea floats through the air and busy shopkeepers keep their customers engaged in determining the perfect brew.

And when the trail ends, you find yourself in Qissa Khwani Bazaar. The famous storytellers market where no longer will you find camels and horses and traders from Samarkand and Bukhara but thriving local businesses and hardly an empty space to step on. The stories here have changed but the atmosphere and the essence of conversation remains the same.

There are other places in Peshawar that carry countless stories and distant memories – Khudadad Hamam, Chitrali Bazaar, All Saint’s Church, to name a few – because while time may run out to visit the history of Peshawar, the list of places will not. Sometimes it seems that even living through 2,500 years of history is still not enough to uncover all the secrets of the past.

Photo by Uzair Aziz