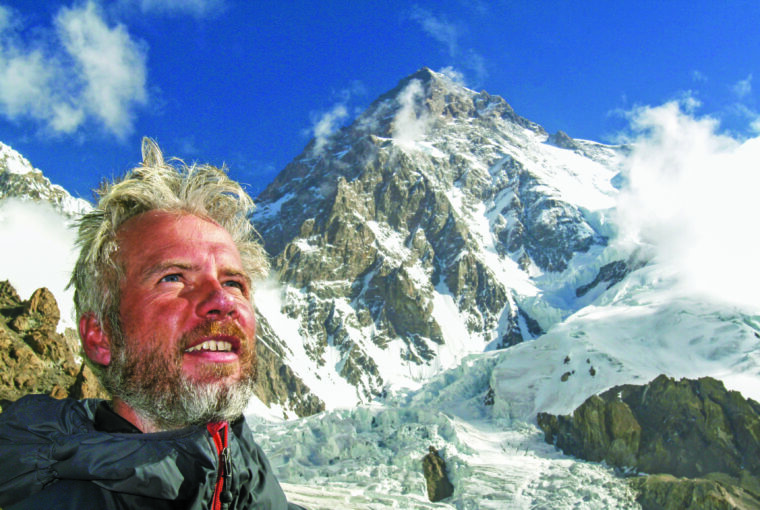

THE SURVIVOR – WILCO VAN ROOIJEN

ON K2, PAKISTAN & BONDS OF HUMAN ENDURANCE

In 2008, Dutch climber, Wilco van Rooijen summited the mighty K2. That same year as a hanging serac fell, many climbers met a fatal end on their journey down, but he survived to tell the tale. It’s been a few years since then but the lessons learnt along the way are more relevant today than ever. Here, Wilco Van Rooijen shares with DESTINATIONS his story of grit, resilience and human endurance that helped him live.

“ Nature is so overwhelming that you have to fight every step of the way to reach the base camp. It’s one of the hardest treks on earth”

Hi Wilco, let’s start by talking about the question that is generally on a reader’s mind when they hear about mountaineering adventures in Pakistan: how did you decide to come to K2 first and not head out East for technically the World’s Highest Peak, Everest?

It all started with me walking with my parents in the Alps. I enjoyed trekking and climbing so much that I continued with it. I took up some instruction courses in the Alps where I started extreme climbing on the most technical routes in the Alps. I kept documenting my experiences and one day, a famous mountaineer from the Netherlands, Ronald Naar, read them. He was planning an expedition to K2 in 1995 and got in touch. It was a huge opportunity as back then, I was just a young mountaineer who had never climbed outside the Alps.

Naar went about organizing the whole thing in a pretty smart manner. He put together a team comprising experienced as well as younger climbers, so that the expedition could benefit from the mental strength of the former and the vigor of the latter.

I was selected with two other young climbers, one of whom was my best friend. It was quite unbelievable that our first experience outside Europe was going to be the mighty K2. Everybody told us that we were too raw and untrained to succeed. We trained hard, but it didn’t end so well as I was hit by rocks and got injured. I had to leave the expedition soon after it started.

It was a harrowing experience leaving the base camp on a helicopter and going through surgery in Pakistan as well as back home in the Netherlands but I survived. This expedition actually gave me the motivation to come back.

In 2006 we came back to climb first Broad Peak and directly after this K2 – a double header, without bottled oxygen! It was on this expedition that I met the intrepid adventurer, Ger McDonnell who later became a really good friend of mine. When this expedition was also not successful, we initiated a third expedition to K2 in 2008. This time,

I was the expedition leader myself. I selected my own team – which included 8 climbers – 5 from the Netherlands, one from Nepal, one Irish fellow from Alaska, Ger McDonnell, and one Australia. We summited this time but tragedy struck soon after our triumph. In what is now known as the deadliest accident in the history of K2 mountaineering, 10 mountaineers lost their lives during descent as massive avalanches glided down. Amongst the casualties was my friend, Ger, who was killed while trying to save other lives.

So that was your best friend?

That was one of my best friends. We met in Alaska as well, climbed the highest mountain together and actually the two of us initiated this expedition together. We worked so hard together to make this dream successful and we did achieve success. I have some amazing memories with him; together, we climbed the highest mountain of North America, Mount Denali; then visuals of summiting K2, dancing, laughing, crying, delirious with happiness, not really knowing what lay in store for us on the way down. 10 climbers were killed on different courses that year as the snow destroyed our ropes on the route through the bottleneck.

Wow! So you finally summited on your third attempt in 2008 and then on the way down you lost your companions and some of your team members. Success was tinged with tragedy, but how do you view your overall experience of climbing, finally summiting K2 and you know getting up there and can you describe the high for us?

It is more than just climbing the mountain because if you are going to Mount Everest, you know you can reach the base camp by car. In Pakistan, however, you know that even the journey towards the base camp is an expedition in itself. You have to travel to the northern territories on bus, then hire a jeep and finally walk 7 days towards the last stretch.

Once you start getting close to the base camp, you realize the mountain is literally fending off against man. Nature is so overwhelming that you have to fight every step of the way to reach the base camp. It’s one of the hardest treks on earth as you realize you’re still not completely acclimatized for 5000+ meters. You’ll meet locals along the way, who become a part of your journey and help your team be successful. The Hunza and Balti people are very very special to me. Without these people there’s no victory on the peaks. International mountaineers are fully dependent on them, they know how to survive when there is no food.

K2 is more than climbing a big rock. It’s the whole culture around it which makes it very special, and that’s why it’s also very difficult to explain to other people because they think, ‘what’s the difference between climbing a mountain in Pakistan or in Nepal, or in South America.’ There is a big difference and that is what makes it worthwhile and unforgettable.

As you said, while Everest basecamp can be reached via normal vehicle, that’s not the case for K2 and other 8000s in Pakistan. In light of this fact, how important do you think is the role that the local community plays, and do they get due recognition? Would you like to say something about them?

There’s not enough recognition and it’s a pity that if you are climbing a mountain, and especially if you are younger, that you are only focused on the success of the summit. What most adventurers don’t realize is that it’s not just about the summit, but the relationships you forge along the way and the journey you make together that’s more important.

I met one of the high-altitude porters in 1995 and then again in 2006. Despite meeting him only twice, he and I developed a great friendship as it’s based on the experiences of extreme conditions we had faced together. You literally depend on each other for survival.

On the mountains, with all our materials and equipment, as we ascend or climb down, there are times when international mountaineers have run out of supplies such as food, water, and that’s when you know, the locals have your back. They know how to survive in these extreme situations and we don’t. It’s their homeland, not ours.

So overall, how was your experience in Pakistan? Did you travel after coming back to Islamabad, did you get to see other parts?

I traveled to Gilgit and experienced first-hand the organic culture of the region. That left a deep impact on me as I realized how unique their world was. These distinct, organic culture streams don’t exist in the developed world anymore. It’s all “modernized”. There is no real sense of adventure, no survival kits required. As long as you have a credit card in your pocket, you’re set. But an interesting life, that makes not. The real joy of life comes from shared experiences of enduring common hardship, overcoming possibly fatal situations, relying on other human beings for your survival. That is when you realize that every individual matters and we are all connected.

“What most adventurers don’t realize is that it’s not just about the summit, but the relationships you forge along the way and the journey you make together that’s more important”

How is climate change going to affect these communities living at the front line of these disasters and catastrophes. When glaciers melt, they are the ones being the hit the hardest. They are the ones who help others live and summit and make the dreams come true. So do you think we can do something for them by talking more about them by giving them greater recognition? How can we uplift those communities through due recognition in international media, or make them part of the mainstream narrative?

I think by sharing our experiences and talking authentically, we can make a difference. Our daily lives in Europe, I feel, can be polarizing. We limit ourselves to our own little orbits. Until we are put in a situation where our lives depend on someone else, and that someone goes out of their way to fight for our survival, you realize how incredible these people are. Traveling is the best way to understand the world. You hear their stories first- hand and then invite them to your home. If more and more people see this exchange, we can start forming a chain between their culture and yours. When I read Three Cups of Tea by Greg Mortenson, my one learning was to see how easy it is to make a difference. All of us, especially everybody in Holland, can support a development project in these communities, whether it is building schools or just providing monetary assistance.

What I like more is the idea of making connections. Once you visit an area, you experience its culture and hospitality first-hand. In bringing back some knowledge and learning from them, the process starts a valuable human chain. We need to continue the chain and form strong human links. That’s the best way forward.

Descriptive articles on the emerging Pakistani destinations, low at Indus and high at K2, offer enticing images of the natural bounty heaped upon the land.. Lucky are the people who live there and, as hosts invite the world, open their hearts to show them around.

Good luck and good friendship offered to hosts and guests, alike.

Ravi Sadana