For anyone interested in Lahore’s colonial past, a walk down lower Mall Road serves as the ideal history lesson. The neighbourhood, which houses some of the city’s most important educational and cultural institutions, provides a vivid illustration of colonial architecture – whether in the imposing façade of the Government College building, the sprawling National College of Arts or the Tollington Market. Perhaps the grandest example is provided by the Lahore Museum, erected in 1894 but displaying a repository of historical artifacts that can be traced back to as early as 6 BC.

While the rich collections housed within the museum have enthralled cultural enthusiasts and history buffs over the decades, the building is a work of art in itself. With its grand domes, majestic red brick exterior, a beautiful marble portico framing the entrance and Mughal-era details in the doorways, it is a striking landmark that inspires awe.

A steady stream of visitors can be seen lining up to pay the Rs. 20 entrance fee (Rs. 10 for children) or picnicking in lawns nestled in the shadow of the picturesque building throughout the week. According to the museum’s present director, Sumaira Samad, the public’s engagement with the historical institution is a result not only of its accessibility but is rooted in its history.

“The museum was created as a public institution and was one of the few institutions for which public funding was raised. At that time, it was a novel idea for people to be able to see things that they had only heard or read about; or which were confined to the homes of the rich only. This exercise to raise money gave them a sense of ownership and involvement, which was one of the reasons for the museum’s huge success even in its initial days,” explains Ms. Samad.

Originally established in the nearby Wazir Khan’s Baradari in 1855, the museum soon outgrew the limited space and was shifted to the Tollington Market. Back then, it was used as an exhibition space for antiquities as well as agricultural and industrial goods. As public interest in the museum and its burgeoning collections grew, the need was felt for a purpose-build space and the Lahore Museum as we know it was created in 1894.

Three years into her tenure as Director, Ms. Samad says she continues to be amazed every day by the breadth of the collections owned by the museum. “It contains such an amazing treasure of our heritage and it is truly a cosmopolitan place, depicting our interesting and vast history. One might read about an ancient civilization such as Gandhara in history books but the impact of seeing it displayed here, that sense of immediacy and connection that is forged, is an incomparable feeling,” she states.

Incidentally, the museum’s Gandhara gallery is its most celebrated, drawing visitors not only from across Pakistan but countries such as Japan and South Korea, who flock to see its extensive exhibit of Buddhist sculpture which depicts the life story of Buddha in a fascinating series of friezes, panels and statues. The most famous amongst them, and one that is considered the museum’s crowning glory, is the statue of the Fasting Buddha – one of the rarest and most intricate examples of Gandharan art.

The museum’s coin collection is also noteworthy, and includes coins from sixth century BC issued during the time of the Achaemenian Empire. Although the extensive collection is made up of over 40,000 pieces, Ms. Samad reveals that only a fraction of those are on display and out of the exhibited pieces, a majority are replicas.

The director is determined to use her time as head of the institution to create better engagement with the public and encourage a richer dialogue. One of the best ways to do that, she maintains, is through collaboration. “I believe that collaboration is integral to the growth of museums. You need to involve people with different skills and expertise; museums require and thrive on interaction,” she says.

One such collaborative exhibition was held in February in partnership with the Lahore Literary Festival. Inaugurated by art historian B.N. Goswami, it gave the museum a chance to display its rich collection of “Pahari” miniatures, a genre of miniature painting that originated in the hills of Punjab. The exhibition made public works that had not been displayed since the time of partition. “People should get a chance to see everything,” declares Ms. Samad. “It is, after all, their history and their past.”

Did you know?

With over 20 galleries displaying the rich cultural heritage of the region, the Lahore Museum is the largest space dedicated to arts and antiquities in the country. The collections housed within its magnificent red brick structure include the Indus Valley Civilization, ancient manuscripts, miniatures, Islamic art, arms and armoury and contemporary art to name just a few. While it depicts our national heritage, it is also cosmopolitan in nature, showcasing artifacts from Burma, Bhutan, Nepal, Central Asia, the Middle East and Africa.

The current museum building was a product of the joint forces of three great men:

Ganga Ram

Known as the “father of modern Lahore”, Ganga Ram was a civil engineer and philanthropist who oversaw the construction of many of Lahore’s grand buildings including the GPO, Aitchison College and the Lahore Museum.

Bhai Ram Singh

Singh was one of the most celebrated architects of pre-partition India. A student of Kipling, he impressed his teacher with his talent and was handpicked to work on the Lahore Museum project. He also redesigned the Mayo College of Arts and was appointed its Vice Principal in 1896.

John Lockwood Kipling

Impressed by the richness of Indian art, teacher and illustrator Kipling arrived in India from London in 1865. Ten years later, he was appointed Principal of Mayo School of Arts (present day National College of Arts). During his tenure, he helped design the new building for the Lahore Museum and also served as one of its first curators. His son Rudyard would go on to fictionalize and immortalize their shared love for the museum and its surrounding areas in the classic, “Kim”.

The Exhibit “Re-discovering Harappa”

In its quest to generate greater interest and engage with a wider audience, the Lahore Museum, in partnership with UNESCO, recently organized a cultural and educational initiative on the fascinating yet underemphasized Indus Valley Civilization. Titled “Rediscovering Harappa”, the special exhibition featured ancient Harappan artifacts from the museum’s permanent collection juxtaposed with the works of contemporary potters Sheherzade Alam and Mohammad Nawaz, both of whom found their inspiration within the ancient civilization.

Why Harappa

The Indus Valley Civilization (3300 to 1300 BC), also referred to as the Harappan civilization, is one of the three ancient civilizations of the world. While its contemporaries, the Egyptian and the Mesopotamian civilizations, have received global attention given their ostentatious and larger than life nature, ancient Harappa has remained in the shadows. “We wanted to focus on Harappa because it’s not appreciated enough,” explains Ms. Samad. “While it might not be spectacular to look at, it was far more advanced and modern than its contemporaries. It is the bedrock of who we are today.”

Dr. Tehnyat Majeed, chief curator of the special exhibition, says that the most valuable lesson one can learn from the Indus civilization, and one that she wanted to share with students through the project’s educational component, was to celebrate the extraordinary in the very ordinary things of life. “The most pervasive quality of Indus remains is that of humility: there is no glorified individual, no palaces, no overt display of wealth in their homes, nor in their graves. Most Indus objects are small and unassuming and for that reason easily dismissed as commonplace.”

Yet, given their skill in urban planning, uniquely egalitarian societal structure and expertise in trade, the Indus people were anything but ordinary.

Some of the most striking features of this ancient civilization that once occupied the land we now live on highlighted through “Rediscovering Harappa” are:

Symbols – the swastika and the unicorn

The modern world’s interpretation of the symbol of the swastika is largely negative, thanks to its usurpation by Nazi Germany, but it was known to signify well-being in ancient cultures. Some of the earliest examples of the swastika were engraved on decorative seals found among Harappan ruins.

The unicorn, often thought to be the product of western mythology, also appears on seals discovered in the Indus region. The bull-like creature with a single horn appears on numerous seals and whether it depicts a real or a mythical animal remains unclear.

Games and toys

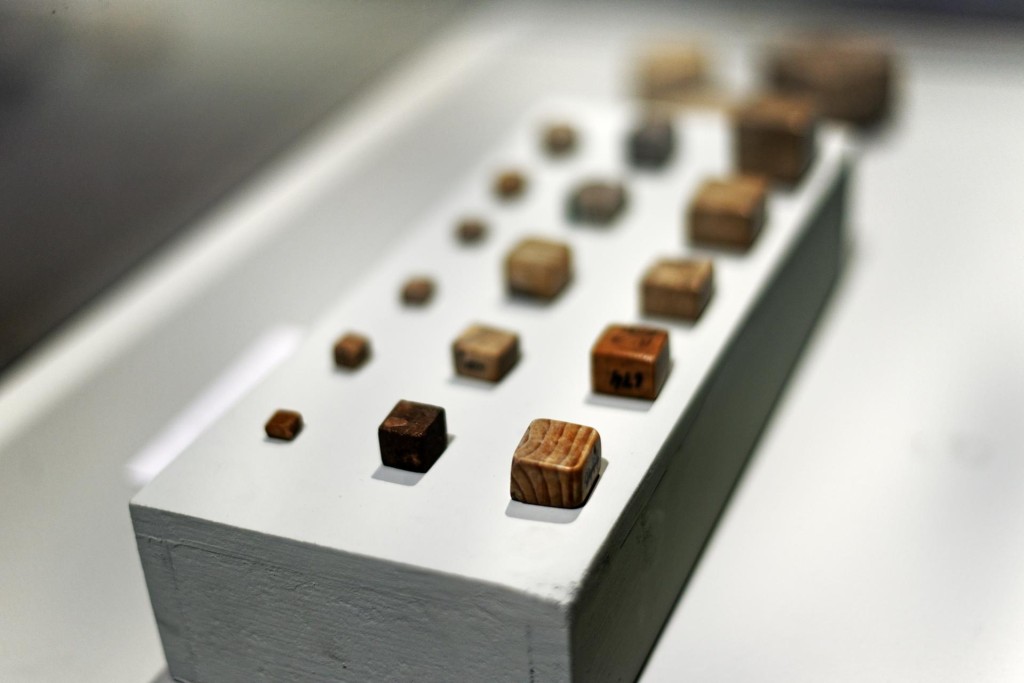

The Harappans are believed to be the first people to have used the dice. The cubical dice found in Harappa is almost exactly like the one we use nowadays, more than 5,000 years on. Remains of a board game, similar in style to modern-day chess, have also been discovered.

Terracotta toy figurines, depicting animals such as bulls and oxen as well as movable carts similar to what we see in rural areas today, were intricately detailed and very realistic.

Earliest example of democracy

There is no evidence to suggest the existence of hierarchal structures within the Harappan society. The houses appear to be more or less equal in size and no trace of a ruling class or group living in luxury has been found. This lack of social disparity is a particularly unique aspect of the ancient civilization.

Trade, not war

The discovery of an extensive and consistent metric system speaks of a sophisticated trade network. The Harappans were skilled in commerce and used their expertise in the area to connect with far-off communities and expand. This is contrast to other civilizations of the time, which were warring societies and usurped territory by killing others. Very little evidence of violence has, in fact, been discovered in Harappa. The bronze spears and arrow-heads that have been discovered are believed to have been used primarily for hunting.

An urban civilization

Harappa is considered to be the first urban civilization, with its exceptional town planning, a sophisticated system of draining and sewerage the likes of which did not appear in any western society till much later, as well as granaries for food storage and massive walls for protection.