Shehroze Kashif has set many world records in mountaineering but there is one he is singularly focused on: being the young- est person in the world to stand on the summit of all 14 of the world’s 8,000m peaks.

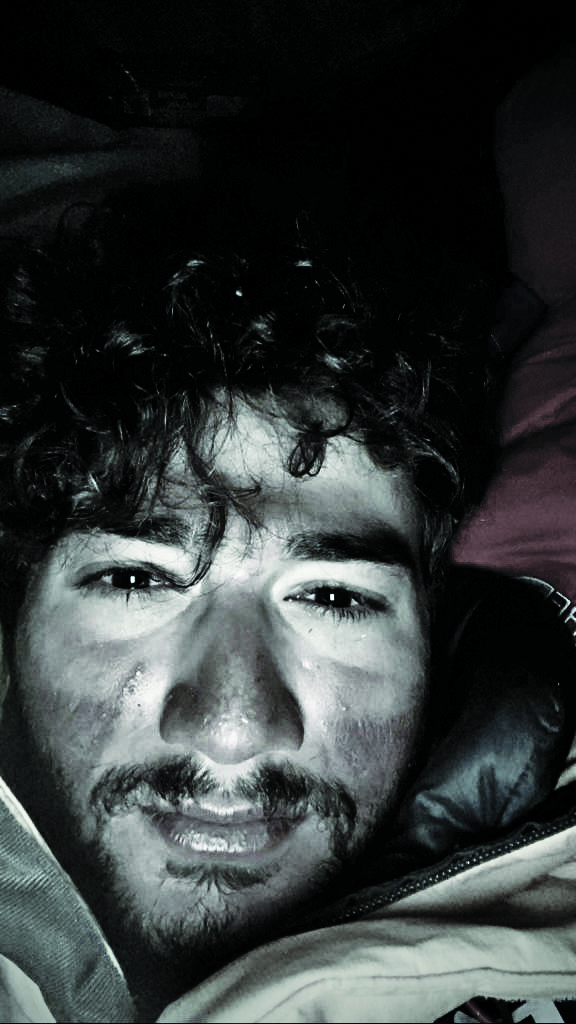

There was a moment on the mountain when Shehroze Kashif thought he was going to die. He was stranded just a few hundred meters below the summit of Nanga Parbat, between rock, snow and ice, in sub-zero temperatures that plunged even further as night fell. One of Pakistan’s most experienced and strongest climbers, Fazal Ali, was with him. They had no cover, no tent and no sleeping bags to keep them warm; and had been without food or water for 30-plus hours.

To make things worse, they had also run out of oxygen. Shehroze’s Garmin tracking device, and what he used to communicate with the team down at basecamp, had also run out of battery. Together, they dug into the snow preparing to spend the night at an altitude of 7,500m where no known living thing is known to survive and which is commonly known in mountaineering lingo as the death zone.

The death zone is any area above an altitude where the pressure of oxygen in the atmosphere is insufficient to sustain human life for an extended period of time. Starved for oxygen, the cells of your body start dying slowly. Shehroze and Fazal didn’t have a lot of time. They needed to descend the mountain fast.

“I really believed that was the end”

But thick clouds had enveloped the mountain shortly after their summit the night before. And these clouds prevented them from finding a trail. Going down blind was not an option. It was too dangerous. They had spent nearly 24 hours in the death zone. Eventually, Shehroze started to hallucinate — one of the more advanced signs of hypoxia. And at this altitude, even rescues are extremely rare. “I really believed that was the end,” says Shehroze. “I started hallucinating. I had visions of being rescued but then I’d blink and see snow-covered mountains all around me.”

But then the dawn broke. “I saw a flicker of light in the horizon, so we decided to get up,” relates Shehroze. “It took us 6 hours to make our way down to Camp 3. And we started to descend safely.” They made it. And in the process, Shehroze also made history: On July 5th, 2022, he became the youngest mountaineer to summit the Nanga Parbat.

The youngest person on some of the world’s highest peaks:

It takes most people a lifetime to do what Shehroze Kashif has done in the span of a few years. Shehroze Kashif is the youngest person in the world who is attempting to summit all 14 of the world’s 8,000m mountains. So, far he’s managed to climb 10 of those, which include the likes of Everest (8,849m), Lhotse (8,516m), Makalu (8,481m), Manaslu (8,163m) and Kanchenjunga (8,586m) in Nepal and, K2 (8,611m), Gasherbrum I (8,080m), Gasherbrum II (8,035m), Broad Peak (8,051m) and Nanga Parbat (8,126m) in Pakistan. The 20-year-old is a global record holder on six of these peaks. He’s the youngest person in the world to have stood on the summits of Everest, K2, Kanchenjunga, Broad Peak, Nanga Parbat, Gasherbrum1 and II.

A race against time:

Shehroze only has four more mountains to go… and he’s running out of time. He must climb the remaining four 8,000m mountains — Cho Oyu, Annapurna, Shishapangma and Dhaulagiri in Nepal — this year otherwise he risks forfeiting to other foreign contenders who are in the same race.

It’s harder to climb an 8,000m mountain than going into space

The total number of people in this world, historically, who have stood on top of an 8,000m mountain is less than those that have gone into outer space.

Imagine, going into space is easier than climbing

an 8,000m mountain. It not only requires a near superhuman level of fitness, but also an enormous amount of passion, perseverance, stubbornness and most importantly, nerves of steel. The altitudes at which these mountain climbers operate are so precarious that their body starts to die of oxygen deprivation when they are on top. Big Mountain climbers, especially those that climb 8,000m mountains like Shehroze, do this dance of death very often. It’s an occupational hazard.

“The lesson I learned on Nanga Parbat was to never give up”

“The lesson I learned on Nanga Parbat was to never give up,” says Shehroze, who has big plans of revolutionizing the mountaineering industry

in Pakistan. “If I was stronger than the mountain, I’d have tried to find the way through those clouds as well,” he says, implying that he would’ve been dead if he had. “I’m not stronger than the mountains. We have to respect nature.”

He’s had near death experiences or witnessed death on these mountains many times. But Shehroze is also keenly aware of the importance of taking care of yourself first on these dangerous altitudes and on following strict safety protocols. It’s what brought him back down when many others didn’t.

As for whether he has nerves of steel, I asked him how long it took him to head back into the mountains after he spent, what he dubs himself, as the scariest night of his life, staring at death in the face, high up in the mountains where no one could see, hear or reach him? “The next day,” he says, without a moment’s hesitation.

Shehroze may have been born and bred in the plains of Punjab, but his heart and his soul is in the mountains.